Nothing was simpler for Liston to fathom than the world between the ropes—step, jab, hook—and nothing was more unyielding than the secrets of living outside them. He was a mob fighter right out of prison. One of his managers, Frank Mitchell, the publisher of the St. Louis .Argus, who had been arrested numerous times on suspicion of gambling, was a known front for John Vitale, St. Louis's reigning hoodlum. Vitale had tics to organized crime's two most notorious boxing manipulators: Frankie Carbo and Carbo's lieutenant, Frank (Blinky) Palermo, who controlled mob fighters out of Philadelphia. Vitale was in the construction business (among others), and when Liston was fighting, one of his jobs was cracking heads and keeping black laborers in line. Liston always publicly denied this, but years later he confided his role to one of his closest Las Vegas friends, Davey Pearl, a boxing referee. "He told me that when he was in St. Louis, he worked as a labor goon." says Pearl, "breaking up strikes."

Not pleased with the company Liston was keeping—one of his pals was 385-pound Barney Baker, a reputed head cracker for the Teamsters—the St. Louis police kept stopping Liston, on sight and without cause, until, on May 5, 1956, 3½ years after his release from prison, Liston assaulted a St. Louis policeman, took his gun, left the cop lying in an alley and hid the weapon at a sister's house. The officer suffered a broken knee and gashed face. The following December, Liston began serving nine months in the city workhouse.

Soon after his release Liston had his second run-in with a St. Louis cop. The officer had creased Liston's skull with a nightstick, and two weeks later the fighter returned the favor by depositing the fellow headfirst in a trash can. Liston then tied St. Louis for Philadelphia, where Palermo installed one of his pals, Joseph (Pep) Barone, as Liston's manager, and Liston at once began fighting the biggest toughs in the division. He stopped Bethea, who spit out seven teeth, in the first round. Valdes fell in three, and so did Williams. Harris swooned in one, and Policy fell like a tree in three. Eddie Machen ran for 12 rounds but lost the decision. Albert Westphal keeled in one. Now Liston had one final fight to win. Only Patterson stood between him and the title.

Whether or not Patterson should deign to fight the ex-con led, at the time, to a weighty moral debate among the nation's reigning sages of sport. What sharpened the lines were Liston's recurring problems with the law in Philadelphia, including a variety of charges stemming from a June 1961 incident in Fairmount Park. Liston and a companion had been arrested for stopping a female motorist after dark and shining a light in her car. All charges, including impersonating a police officer, were eventually dropped. A month before, Liston had been brought in for loitering on a street corner. That charge too was dropped. More damaging were revelations that he was, indeed, a mob fighter, with a labor goon's history. In 1960, when Liston was the No. 1 heavyweight contender, testimony before a U.S. Senate subcommittee probing underworld control of boxing had revealed that Carbo and Palermo together owned a majority interest in him. Of this, Liston said, he knew nothing. "Pep Barone handles me," he said. "Do you think that people like [Carbo and Palermo] ought to remain in the sport of boxing?" asked the committee chairman, Tennessee senator Estes Kefauver.

"I wouldn't pass judgment on no one," Liston replied. "I haven't been perfect myself."

In an act of public cleansing after the Fairmount Park incident, Liston spent three months living in a house belonging to the Loyola Catholic Church in Denver, where he had met Father Edward Murphy, a Jesuit priest, while training to fight Folley in 1960. Murphy, who died in 1975, became Liston's spiritual counselor and teacher. "Murph gave him a house to live in and tried to get him to stop drinking," Father Thomas Kelly, one of Murphy's closest friends, recalls. "That was his biggest problem. You could smell him in the mornings. Oh, poor Sonny. He was just an accident waiting to happen. Murph used to say, 'Pray for the poor bastard.' "

But even Liston's sojourn in Denver didn't still the debate over his worthiness to fight for the title. In this bout between good and evil, the clearest voice belonged to New York Herald-Tribune columnist Red Smith: "Should a man with a record of violent crime be given a chance to become champion of the world? Is America less sinful today than in 1853 when John Morrissey, a saloon brawler and political head-breaker out of Troy, N.Y., fought Yankee Sullivan, lamister from the Australian penal colony in Botany Bay? In our time, hoodlums have held championships with distinction. Boxing may be purer since their departure; it is not healthier." Since he could not read, Liston missed many pearls, but friends read scores of columns to him. When Bar-one was under fire for his mob ties, Liston quipped, "I got to get me a manager that's not hot—like Estes Kefauver." Instead, he got George Katz, who quickly came to appreciate Liston's droll sense of humor. Katz managed Liston for 10% of his purses, and as the two sat in court at Liston's hearing for the Fairmount Park incident, Liston leaned over to Katz and said, "If I get time, you're entitled to 10 percent of it."

Liston was far from the sullen, insensitive brute of the popular imagination. Liston and McKinney

would take long walks between workouts, and during them Liston would recite the complete dialogue and sound effects of the comedy routines of black comedians like Pigmeat Markham and Redd Foxx. "He could imitate what he heard, down to creaking doors and women's voices," says McKinney. "It was hilarious hearing him do falsetto."

Liston also fabricated quaint metaphors to describe phenomena ranging from brain damage to the effects of his jab: "The middle of a fighter's forehead is like a dog's tail. Cut off the tail and the dog goes all which way 'cause he ain't got no more balance, It's the same with a fighter's forehead."

He lectured occasionally on the unconscious, though not in the Freudian sense. Setting the knuckles of one fist into the grooves between the knuckles of the other fist, he would explain: "Sec, the different parts of the brain set in little cups like this. When you get hit a terrible shot—pop!—the brain flops out of them cups and you're knocked out. Then the brain settles back in the cups and you come to. But after this happens enough times, or sometimes even once if the shot's hard enough, the brain don't settle back right in them cups, and that's when you start needing other people to help you get around.

So it was that Liston vowed to hit Patterson on the dog's tail until his brain Hopped out of its cups. Actually, he missed the tail and hit the chin. Patterson was gone. Liston had trained to the minute, and he was a better fighter that night than he would ever be again. And what had it gotten him? Obviously, nothing in his life had changed. He left Philadelphia after he won the title, because he believed he was being harassed by the police of Fairmount Park, through which he had to drive to get from the gym to his home. At one point he was stopped for "driving too slow" through the park. That did it. In 1963 he moved to Denver, where he announced, "I'd rather be a lamppost in Denver than the mayor of Philadelphia." At times, in fact, things were not much better in the Rockies. "For a while the Denver police pulled him over every day," says Ray Schoeninger, a former Liston sparring partner. "They must have stopped him 100 times outside City Park. He'd run on the golf course, and as he left in his car, they'd stop him. Twenty-five days in a row. Same two cops. They thought it was a big joke. It made me ashamed of being a Denver native. Sad they never let him live in peace."

Liston's disputes were not always with the police. After he won the title, he walked into the dining room of the Beverly Rodeo Hotel in Hollywood and approached the table at which former rumrunner Moe Dalitz, head of the Desert Inn in Las Vegas and a boss of the old Cleveland mob, was eating. The two men spoke. Liston made a fist and cocked it. Speaking very distinctly, Dalitz said, "If you hit me, nigger, you better kill me. Because if you don't. I'll make one telephone call, and you'll be dead in 24 hours." Liston wheeled and left. The police and Dalitz were hardly Liston's only tormentors. There was a new and even more inescapable disturber of his peace: the boisterous Clay. Not that Liston at first took notice. After clubbing Patterson, he took no one seriously. He hardly trained for the rematch in Las Vegas. Clay, who hung around Liston's gym while the champion went through the motions of preparing for Patterson, heckled him relentlessly. Already a minor poet, Clay would yell at Liston, "Sonny is a fatty. I'm gonna whip him like his daddy!" One afternoon he rushed up to Liston, pointed to him and shouted, "He ain't whipped nobody! Who's he whipped?" Liston, sitting down, patted a leg and said, "Little boy, come sit in my lap." But Clay wouldn't sit; he was too busy running around and bellowing. "The beast is on the run!"

Liston spotted Clay one day in the Thunderbird Casino, walked up behind him and tapped him on the shoulder. Clay turned, and Liston cuffed him hard with the back of his hand. The place was silent. Young Clay looked frightened. "What you do that for?" he said.

" 'Cause you're too——fresh," Liston said. As he headed out of the casino, he said, "I got the punk's heart now."

That incident would be decisive in determining the outcome of the first Liston-Clay fight, seven months later. "Sonny had no respect for Clay after that," McKinney says. "Sonny thought all he had to do was take off his robe and Clay would faint. He made this colossal misjudgment. He didn't train at all."

If he had no respect for Clay, Liston was like a child around the radio hero of his boyhood, Joe Louis. When George Lois, then the art director at Esquire, decided to try the black-Santa cover, he asked his friend Louis to approach Liston. Liston grudgingly agreed to do the shoot in Las Vegas. Photographer Carl Fischer snapped one photograph, whereupon Liston rose, took off the cap and said, "That's it." He started out the door. Lois grabbed Liston's arm. The fighter stopped and stared at the art director. "I let his arm go," Lois recalls.

While Liston returned to the craps

tables, Lois was in a panic. "One picture!" Lois says. "You need to take 50, 100 pictures to make sure you get it right." He ran to Louis, who understood Lois's dilemma. Louis found Liston shooting craps, walked up behind him, reached up, grabbed him by an car and marched him out of the casino. Bent over like a puppy on a leash, Liston followed Louis to the elevator, with Louis muttering, "Come on, git!" The cover shoot resumed.

A few months later, of course, Clay handled Liston almost as easily. Liston stalked and chased, but Clay was too quick and too fit for him. By the end of the third round Liston knew that his title was in peril, and he grew desperate. One of Liston's trainers, Joe Pollino, confessed to McKinney years later that Liston ordered him to rub an astringent compound on his gloves before the fourth round. Pollino complied. Liston shoved his gloves into Clay's face in the fourth, and the challenger's eyes began burning and tearing so severely that he could not see. In his corner, before the fifth round, Clay told his handlers that he could not go on. His trainer, Angelo Dundee, had to literally push him into the ring. Moving backward faster than Liston moved forward, Clay ducked and dodged as Liston lunged after him. He survived the round.

By the sixth Clay could sec clearly again, and as he danced and jabbed, hitting Liston at will, the champion appeared to age three years in three minutes. At the end of that round, bleeding and exhausted, he could foresee his humiliating end. His left shoulder had been injured—he could no longer throw an effective punch with it—and so he stayed on his stool, just sat there at the bell to start Round 7.

There were cries that Liston had thrown the fight. That night Conrad, Liston's publicist, went to see him in his room, where Liston was sitting in bed, drinking.

"What are they saying about the fight?" Liston asked.

"That you took a dive," said Conrad.

Liston raged. "Me? Sell my title? Those dirty bastards!" He threw his glass and shattered it against the wall.

The charges of a fix in that fight were nothing compared with what would be said about the rematch, in Lewiston, Maine, during which Liston solidified his place in boxing history. Ali, as the young champion was now widely called, threw one blow, an overhand right so dubious that it became known as the Phantom Punch, and suddenly Liston was on his back. The crowd came to its feet in anger, yelling. "Fake! Fake!"

Ali looked down at the fallen Liston, cocked a fist and screamed at him, "Get up and fight, sucker! Get up and fight!"

There was chaos. Referee Joe Walcott, having vainly tried to push Ali to a neutral corner, did not start a count, and Liston lay there unwilling to rise. "Clay caught me cold," Liston would recall. "Anybody can get caught in the first round, before you work up a sweat. Clay stood over me. I never blacked out. But I wasn't gonna get up, either, not with him standing over me. Sec, you can't get up without putting one hand on the floor, and so I couldn't protect myself."

The finish was as ugly as a Maine lobster. Walcott finally moved Ali back, and as Liston rose, Walcott wiped off his gloves and stepped away. Ali and Liston resumed fighting. Immediately, Nat Fleischer, editor of The Ring magazine, who was sitting next to the official timer, began shouting for Walcott to stop the fight. Liston had been down for 17 seconds, and Fleischer, who had no actual authority at ringside, thought the fight should have been declared over. Walcott left the two men fighting and walked over to confer with Fleischer. Though he had never even started a count, Walcott then turned back to the fighters and, incredibly, stepped between them to end the fight. "I was never counted out," Liston said later. "I coulda got up right after I was hit."

No one believed him, of course, and even Geraldine had her doubts. Ted King, one of Liston's seconds, recalls her angrily accusing Sonny later that night of going in the water.

"You could have gotten up, and you stayed down!" she cried.

Liston looked pleadingly at King. "Tell her, Teddy," he said. "Tell her I got hit."

Some who were at ringside that night, and others who have studied the films, insist that Ali indeed connected with a shattering right. But Liston's performance in Lewiston has long been perceived as a tank job, and not a convincing one at that. One of Liston's assistant trainers claims that Liston threw the fight for fear of being murdered. King now says that two well-dressed Black Muslims showed up in Maine before the fight—Ali had just become a Muslim—and warned Liston, "You get killed if you win." So, according to King, Liston chose a safer ending. It seems fitting somehow that Liston should spend the last moments of the best years of his life on his back while the crowd showered him with howls of execration. Liston's two losses to Ali ended the short, unhappy reign of the most feared—and the most relentlessly hounded—prizefighter of his time.

Liston never really retired from the ring. After two years of fighting pushovers in Europe, he returned to the U.S. and began a comeback of sorts in 1968. He knocked out all seven of his opponents that year and won three more matches in 1969 before an old sparring partner, Leotis Martin, stopped him in the ninth round of a bout on Dec. 6. That killed any chance at a title shot. On June 29, 1970, he fought Chuck Wepner in Jersey City. Tocco, Liston's old trainer from the early St. Louis days, prepared him for the light against the man known as the Bayonne Bleeder. Listen hammered Wepner with jabs, and in the sixth round Tocco began pleading with the referee to stop the fight. "It was like blood was coming out of a hydrant," says Tocco. The referee stopped the bout in the 10th: Wepner needed 57 stitches to close his face.

That was Liston's last fight, He earned $13,000 for it, but he wound up broke nonetheless. Several weeks earlier, Liston had asked Banker to place a $10,000 bet for him on undefeated heavyweight contender Mac Foster to whip veteran Jerry Quarry. Quarry stopped Foster in the sixth round, and Liston promised Banker he would pay him back after the Wepner fight. When Liston and Banker boarded the flight back to Las Vegas, Liston opened a brown paper bag, carefully counted out $10,000 in small bills and handed the wad to Banker. "He gave the other $3,000 to guys in his corner," Banker said. "That left him with nothing."

In the last weeks of his life Liston was moving with a fast crowd. At one point a Las Vegas sheriff warned Banker, through a mutual friend, to stay away from Liston. "We're looking into a drug deal," said the sheriff. "Liston is getting involved with the wrong people." At about the same time two Las Vegas policemen stopped by the gym and told Tocco that Liston had recently turned up at a house that would be the target of a drug raid. Says Tocco, "For a week the police were parked in a lot across the street, watching when Sonny came and who he left with."

On the night Geraldine found his body, Liston had been dead at least six days, and an autopsy revealed traces of morphine and codeine of a type produced by the breakdown of heroin in the body. His body was so decomposed that tests were inconclusive—officially, he died of lung congestion and heart failure—but circumstantial evidence suggests that he died of a heroin overdose. There were fresh needle marks on one of his arms. An investigating officer, Sergeant Gary Beckwith, found a small amount of marijuana along with heroin and a syringe in the house. Geraldine, Banker and Pearl all say that they had no knowledge of Liston's involvement with drugs, but law enforcement officials say they have reason to believe that Liston was a regular heroin user. Those closest to him may not have known of his drug use. Liston had apparently lived two lives for years.

Pearl was always hearing reports of Liston's drinking binges, but Liston was a teetotaler around Pearl. "I never saw Sonny take a drink." says Pearl. "Ever. And I was with him hundreds of times over the last five years of his life. He'd leave me at night, and the next morning someone would say to me, 'You should have seen your boy, Liston, last night. Was he ever drunk!' I once asked him, 'What is this? You leave me at night and go out and get drunk?' He just looked at me. I never, ever suspected him of doing dope. I'm telling you, I don't think he did."

Some police officials and not a few old friends think that Liston may have been murdered, though they have no way of proving it now. Conrad believed that Liston had become deeply involved in a loan-sharking ring in Las Vegas, as a bill collector, and that he had tried to muscle in for a bigger share of the action. His employers got him drunk. Conrad surmised, took him home and stuck him with a needle. There are police in Las Vegas who say they believe—but are unable to prove—that Liston was the target of a hit ordered by Ash Resnick, an old associate of Liston's with whom he was having a dispute over money. Resnick died in 1989.

Geraldine has trouble comprehending all that talk about heroin or murder. "If he was killed, I don't know who would do it," she says. "If he was doing drugs, he didn't act like he was drugged. Sonny wasn't on dope. He had high blood pressure, and he had been out drinking in late December. As far as I'm concerned, he had a heart attack. Case closed."

There is no persuasive explanation of how Liston died, so the speculation continues.

Liston is buried in Paradise Memorial Gardens, in Las Vegas, directly under the flight path for planes approaching McCarran International Airport. The brass plate on the grave is tarnished now, but the epitaph is clear under his name and the years of his life. It reads simply: A MAN Twenty years ago father Murphy Hew in from Denver to give the eulogy, then went home and wept for an hour before he could compose himself enough to tell Father Kelly about the funeral. "They had the funeral procession down the Strip." Murphy said. "Can you imagine that? People came out of the hotels to watch him pass. They stopped everything. They used him all his life. They were still using him on the way to the cemetery. There he was, another Las Vegas show. God help us."

In the end, it seemed fitting that Liston, after all those years, should finally play to a friendly crowd on the way to his own burial—with a police escort, the most ironic touch of all.

Geraldine remained in Las Vegas for nine years after Sonny died—she was a casino hostess—then returned to St. Louis, where she had met Sonny after his parole, when he was working in a munitions factory. She has never remarried, and today works as a medical technician. "He was a great guy, great with me, great with kids, a gentle man," says Geraldine.

With Geraldine gone from Las Vegas, few visit Sonny's grave anymore. Every couple of minutes a plane roars over, shaking the earth and rattling the broken plastic flowers that someone placed in the metal urn atop his headstone. "Every once in a while someone comes by and asks to see where he's buried, "says a cemetery worker. "But not many anymore. Not often."

In boxing, if you want to get a good sense of what a fighter was like in the ring, his power, skills, etc., you ask the opponents he faced. It's interesting listening to people talk about Sonny Liston, you can get a good sense of what it was like to be in the ring with him. Chuck Wepner fought Liston, Foreman, and Ali and he said that Liston had the best jab, was the strongest, and the best puncher of the three.

Chuck Wepner:

BEST JAB

Sonny Liston: He threw it right from the shoulder, it was short, and he had everything behind it. That’s why it was a hard punch to get away from. I really didn’t get away from it too good. I wound up with 71 stitches, a broken nose and broken left cheekbone. Most of it was from the jab.

STRONGEST

Liston: That would have to be Sonny Liston or George Foreman. I was a brawler, I was an intimidator, I tried to go out and push a guy around, rough ’em up early. Sonny and George, as soon you banged into them, it was like banging into a brick wall. They didn’t move. I’d say Liston in his prime.

BEST PUNCHER

Liston: It hurts if anybody hits you. I could always take it, absorb it and come back, but with Liston, after you got hit by him, you were very weary to make that move again. We trained to stick a jab and move with Liston, but he stayed right on your chest, throwing punches. Not like Ali, who would hit you and get out. George was powerful, too. George cut me open pretty early in the fight. I always thought it was a headbutt, but it was an accidental head clash. He did cut me open, and they stopped it after the third round. Probably Sonny Liston was the best puncher.

Personally, my favorite Sonny Liston fights were his fights with Cleveland "Big Cat" Williams. He fought Williams twice, both fights combined only lasted five rounds. Like Sonny Liston, Cleveland Williams was a murderous puncher himself, and he decided he was going to just go for broke and try to take Liston out in both fights. What we got was two apocalyptic shootouts.

Recalling The Sonny Liston Vs. Cleveland Williams Wars

By James Slater - 01/21/2020

No-one knows for sure when heavyweight king Charles “Sonny” Liston was born, therefore we don’t know how old Liston was when he was at his absolute peak. But there is one fight that stands out as the peak performance of Liston’s entire career: a fight that saw Liston show some truly ferocious punching prowess, a rock of a chin, great speed of hand, superb accuracy and a truly unquenchable thirst for battle. This primed and peaked performance came in March of 1960, as Liston, then (officially) aged 30 or 32 (depending on which official record you go by; really there being no such thing in existence) met fellow monster puncher, the equally carved from granite Cleveland Williams. It’s mindboggling to think how these two superb, and avoided, fighting machines were matched together twice, inside 11 months. Today, both men, with good connections and even better protection (as Muhammad Ali might say) would have been kept apart, at least until one of them won a world title (as both would undoubtedly do today). But Liston and Williams fought in a different time, a far tougher time. And so they went to war, first in April of 1959, and then again in March of the following year. Williams, who was born in 1933, was 47-3 at the time of his return rumble with Liston (the three losses coming against Sylvester Jones, on points in 1953, Bob Satterfield, by KO in 1954, and to Liston in 1959). Williams enjoyed a one-inch height advantage over Sonny, while Liston had the edge in reach at 84” to 80”. In their first encounter was held at Miami Beach, with Liston then being 27-1 (the loss coming on points to Marty Marshall in 1954, later avenged) and the crowd had been treated to a quite magnificent and highly entertaining three-round slugfest. Williams had success early, hitting and hurting a slow-starting Liston; bloodying the older man’s nose. But Liston, a fighter with the single best “poker face” imaginable, never let on if he was in fact hurt. Liston poured it on towards the end of round-two, and then, sensing his man was hurt, decked Williams twice to get the stoppage in the third. It was a great win for Liston; a man who, like Williams, had real trouble finding quality opposition. Three fights, three wins and 11 months later, Liston faced Williams a second time. The return took place in Houston, Texas, and another violent affair unfolded. A fairly even opening round went by, but no-one was expecting the action to last too long. And it didn’t. A great second-round saw both men land with power punches, but once again Liston would not be denied. Sonny had to take a fierce left hook from Williams, however, along with a burst of hurtful follow up blows which had him stuck in a corner, before retaliating with blistering shots of his own. Then, after three consecutive lefts from Williams, Liston landed a cracking overhand right , followed by another right hand that landed flush, and then a perfect left hook to the jaw that dropped his man heavily. Showing great bravery, the badly battered fighter got up at eight – only to be met by a ferocious Liston who was coming to finish him off. With the courageous Williams stuck in the same corner that he himself had just been forced into, Sonny teed off on his wounded target. Blow after blow landed, until Williams slid down the ropes to the floor. He was grimacing in pain as he did so. Somehow, in a truly amazing display of guts, Williams pulled himself upright once more. But the referee had seen enough and he stopped the onrushing Liston in his tracks, putting a stop to the brutal fight. Liston had looked absolutely awesome. As near to unbeatable as anyone could imagine a fighter to look. Indeed, this was the peak Sonny Liston – the most terrifying, the fastest, hardest hitting and just plain best heavyweight on the planet at the time.

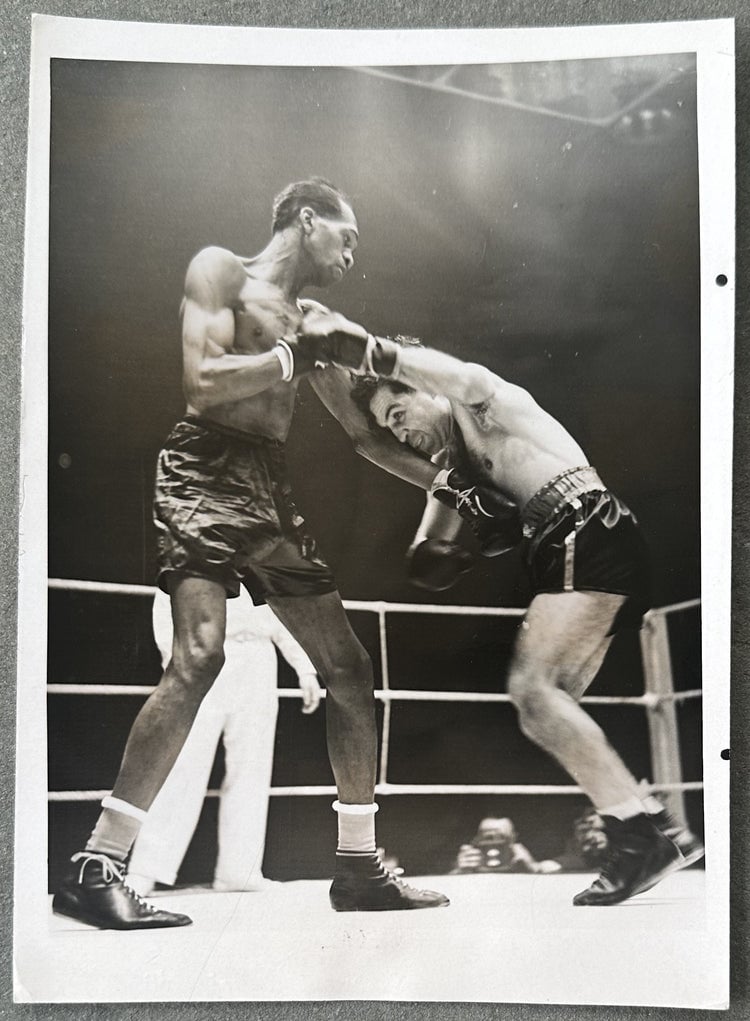

This shot is from the first Sonny Liston-Cleveland Williams fight, great shot, you can see how brutal it was, Liston's nose is broken and bleeding. Williams was a murderous puncher and he caught Liston with some thunderous shots. But this fight really demonstrated what a nightmare Liston was, Williams hit him with the kitchen sink and it just didn't matter, Sonny still smashed him.

Floyd Patterson was an all-time great and he fought Sonny Liston twice, both fights combined lasted a total of two rounds, Sonny Liston needed just 126 seconds to take the heavyweight title from Patterson in 1962 at Comiskey Park. About halfway through the first round, Liston hurt Patterson with a right uppercut. Liston followed with a series of punches, ending with a left hook, that dropped Patterson. He made it to his feet but was unable to beat the referee's count of ten. The contract stated that if Liston won, he would have to give Patterson a rematch within a year. The rematch between Liston and Patterson was almost a carbon copy of the first fight, this time Liston needed only 130 seconds. Liston knocked Patterson down three times, with the fight ending at 2:10 in the first round.

Sonny Liston watches as Albert Westphal sinks to the floor unconscious after a rough 1-2 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1961. Westphal would take minutes to regain consciousness.

This is what it was like being hit by those fists. Sonny Liston may have been legit the most feared fighter in the history of boxing, even moreso than Mike Tyson, and watching this video, it's easy to see why. This is the brutal destruction of Sonny Liston.

Liston training with George Foreman by his side, George Foreman and Sonny Liston had a complex relationship of mentor and mentee, with Liston acting as a formidable sparring partner and a dark mentor to the younger Foreman. Foreman considered sparring with Liston the most dangerous thing he had ever done, and said Liston taught him the importance of the jab and how to back opponents up. Foreman adopted Liston's intimidating stare and fierce persona, which helped him develop his "Bad George" image, though he later found a more spiritual path.

45-year-old Archie Moore, aka "The Old Mongoose," helps beaten foe Alejandro Lavorante to his corner after stopping him in the final round of a 10-round fight in 1962. Lavorante, a 25-year-old from Argentina with only two losses on his record, took a sustained beating against the former light heavyweight champion, but never went down. Lavorante collapsed in his corner and had to be taken from the ring in a stretcher, though he recovered the next day without issue. Unfortunately Lavorante, who was said to have been discovered by former heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey, wouldn't be so lucky as the year progressed. The loss to Moore was followed by a KO loss to a young Muhammad Ali, then another KO loss to a journeyman named John Riggins. Lavorante suffered a cerebral hemorrhage in his loss to Riggins, fell into a coma and underwent an operation. Lavorante recovered enough to regain some movement and speech, but he died at only 27-years-old about 18 months following the Riggins fight.

In 1978, comedian Richard Pryor participated in a benefit boxing match against Muhammad Ali at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles. Despite his amateur boxing background, Pryor found himself outmatched by Ali's speed and skill. During a December 1978 stand-up performance, later released as "Richard Pryor: Live in Concert," he humorously recounted the experience, expressing concern that Ali might have a flashback to his intense bouts with Joe Frazier. Pryor's comedic retelling highlights his ability to find humor in daunting situations.

“Ali came out, he threw about eight punches, man. About a quarter inch from my nose. I said, ‘Shiiiiiiit.’ And I was happy to be in the ring with the champ, you know it was really nice. But my mind kept saying, ‘What happens if this ni**a has one of those Joe Frazier flashbacks?’ You know what I mean like, ‘Round 11, Joe Frazier. BOOM!’ It’ll give me brain damage for life.” - Richard Pryor

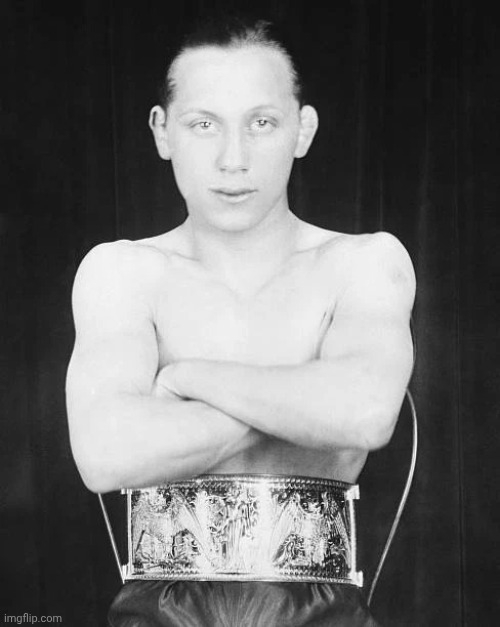

David Montrose, he fought under the ringname "Newsboy Brown", he got that name because he sold newspapers as a teen and learned to box to protect his territory. He put it to good use, he became a great pound-for-pound fighter and a Hall of Famer. The Newsboy fought in the 1920s and 30s as a flyweight and bantamweight, he beat world champions in both weight classes, but none of the fights were for titles. He holds wins over Panama Al Brown, Midget Wolgast, Baby Arizmendi, Frankie Genaro X2, Corporal Izzy Schwartz, Chalky Wright, and Speedy Dado, that's one hell of a resume.

Newsboy Brown

Boxing great Dave Montrose was born in Russia in 1904 and immigrated to the United States as a small boy. He learned to fight at an early age selling newspapers on the street corners of Sioux City, Iowa. He began boxing professionally at the age of 18. He acquired the name "Newsboy Brown" in one of his early fights. The ring announcer, proceeded to introduce him. "In this corner...," he began. Then, realizing he had not bothered to learn the name of the young fighter, whom he knew only to be a newsboy, he continued, "the brown-skinned newsboy.....Newsboy Brown." The name stuck, and Newsboy Brown went on to become one of the most popular prizefighters of the 1920's and '30's.

The grand opening of the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles on August 5, 1925 was a major media event, attended by such celebrities as Jack Dempsey and Rudolph Valentino. The card featured several six round events, one of which matched Newsboy Brown against Frankie Grandetta. Brown, of course, took the decision. By that time a resident of Boyle Heights in Los Angeles, he quickly became a favorite of the local boxing fans, appearing many times in the Olympic Auditorium after that.

Newsboy Brown came about as close as one can to being recognized as a world champion. As a flyweight, he beat world champions Frankie Genaro and Midget Wolgast and fought to two draws with world champion Fidel La Barba. Unfortunately, however, none of these were title fights.

After his second draw with La Barba, Newsboy Brown was acknowledged by many as the logical contender for a shot at La Barba's crown. Before he had that chance, however, La Barba gave up his title to attend Stanford University, throwing the world flyweight championship into dispute. An elimination tournament was held in New York City to determine his successor. It all came down to a final 15 round battle on December 16, 1927 between Newsboy Brown and an ex-soldier from New York named Corporal Izzy Schwartz. Newsboy Brown lost a heartbreaking decision to Schwartz that night. But Schwartz' title was recognized only in New York.

La Barba in the meanwhile had proclaimed his successor to be a veteran flyweight named Johnny McCoy. After his loss to Schwartz, the Newsboy decided to take on McCoy. As the records show, on January 3, 1928, Newsboy Brown defeated Johnny McCoy in Los Angeles to claim the flyweight title. Because of the continuing dispute over the legitimacy of the title, however, the Newsboy's claim was recognized essentially only in California. Eight months later he lost it to Johnny Hill in a 15 round decision in London, England.

He also fought as a bantamweight, against such top contenders as Chalky Wright, who later went on to become World Featherweight Champion from 1941 to 1942. In 1929, Panama Al Brown (no relation) defeated Vidal Gregorio in Long Island City to capture the vacant world bantamweight title, which he successfully defended ten times before finally surrendering it to Baltazar Sangchili on June 1, 1935. In the meantime, however, Newsboy Brown beat World Champion Panama Al Brown in a 15 round bout in Los Angeles on December 15, 1931. Unfortunately, because both fighters weighed in over the 118 point limit, it was a non-title fight, and Newsboy Brown never became world bantamweight champion either.

On March 3, 1931, he won the California Bantamweight title by defeating Speedy Dado in a ten round contest in Los Angeles. He eventually lost it to Philippine champion Young Tommy in a record attendance setting fight in Sacramento, California on January 28, 1932.

After 81 professional fights over 11 years in the ring, he finally hung up the gloves in 1933. He broke into the motion picture business by coaching cowboy star Tom Mix in his fight scenes. As a result of his association with Mix, he landed a job in the properties department of one of the Hollywood studios, where he worked in his later years. Dave Montrose died in 1977 at the age of 73. He is remembered fondly in the boxing community as a tough scrapper with the heart of a lion.

In 1931, Newsboy Brown defeated Panama Al Brown, that alone should tell you what a bada$$ the Newsboy was. Panama Al Brown was no joke, stepping in the ring with Panama was like a mouse trying to fight a birdeater Tarantula, Panama was freakishly tall for a bantam, 5'9" and had a ridiculous wing span with a 72.5 inch reach, he ruled the bantamweight division with an iron fist, holding the title for six years.

Newsboy Brown

Panama Al Brown

Newsboy Brown, veteran of many a ring battle, achieved one of his greatest triumphs, and also provided one of the season's fistic upsets, on December 15, 1931 when he defeated "Panama" Alphonse Brown, bantam champion of the world, in a 10 round thriller at the Los Angeles Olympic Auditorium. No title was at stake, however, because both fighters were over the 118 pound bantamweight limit, the Newsboy going in at 120 ½ pounds, while the Panama boxer weighed 122.

Giving away almost a head in height to the gangling Panamanian, and 4 inches in reach, the Newsboy turned in a fine performance, outscoring his opponent with stinging rights and lefts to the body. Although the Panamanian drew several cautions for head butting during the melee, he also showed flashes of sterling offensive work with hard rights, but the Newsboy always came back to give more than he received.

Newsboy Brown assumed and maintained the aggressor's attitude from start to finish. It took him one round to size up the situation. Then he moved into close quarters, beating his two fists mightily to the champion's midriff. The Newsboy took the second, third, and forth rounds handily. In the fifth, Al Brown managed to land several stiff rights, looping punches that caught the Newsboy by surprise. Again in the seventh and eighth rounds the champion rallied with fury to beat his smaller opponent back and bombard him with punches.

They came to the tenth and final round on fairly even terms. But the Newsboy went whaling away, tore right into the Panamanian and bombarded him viciously about the stomach, now and then crossing things up with snappy left hooks to the chin. In the end, referee Harry Lee passed by the outstretched arm of the surprised champion and hoisted the arm of the fighting Newsboy of Boyle Heights. A sympathetic crown cheered his victory to the echo. The Newsboy had taken 6 rounds to the champion's 3, with one even.

Newsboy Brown (left) and movie star Tom Mix. Tom Mix was a pioneering American cowboy and movie star, famous for his starring roles in early Western films from 1909 to 1935. He was a real-life cowboy and stuntman who performed his own daring tricks, becoming a Hollywood superstar and one of the biggest names of the silent film era.

On top of defeating Panama Al Brown, the Newsboy also defeated all-time great flyweight champions Midget Wolgast and Frankie Genaro, while they were world champions, unfortunately the bouts were non-title, meaning the title wasn't on the line. Footage of Midget Wolgast was discovered back in or around 2010 and it was shocking to say the least, after viewing the footage of Midget Wolgast, the great boxing writer Matt McGrain said: "He's exceptional. I think we're looking at a phenom, personally. Tentatively, everything thing they seemed to make up about (Harry) Greb seems to have been true about this little ****." I've seen the footage of Wolgast and McGrain is correct, he was a phenom, he was decades ahead of his time, he was a switch hitter, very clever, moved like Muhammad Ali, it's very shocking to see that in the 1930s. I'm sorry, but anyone who can defeat Midget Wolgast is a genuine bada$$, and the Newsboy beat him, and it's a crying shame that we don't have any fight film of the Newsboy.

A few more photos of the great Newsboy Brown. I'm a big collector of boxing items, and anything of Newsboy Brown is extremely rare and difficult to find, I wish some of this stuff would pop up on ebay.

Jack Dempsey, "The Manassa Mauler", eating Watermelon a few days before his destruction of Jess Willard. This photo sends chills up my spine, it's like the calm before the storm, Dempsey laid one of the worst beatings ever seen in a boxing ring on Jess Willard, took his heavyweight title, and held it for seven years. That fight was the beginning of a dynasty.

Primo Carnera, aka "The Ambling Alp", sparring with the tallest person who ever lived, Robert Wadlow. At the time of this photo, Carnera was a future heavyweight champion and a giant himself, standing at 6'6". Robert Wadlow would reach an incredible 8'11" and weigh 439 pounds when he died at only 22.

Irish Jerry Quarry with Martin Milner and Kent McCord on the TV show Adam-12, Quarry was a guest star on the show. It's a great show, I've seen every episode of it.

Boxing trainer Teddy Atlas, who is known best for helping assisting in training a young Mike Tyson while acting as an apprentice under Cus D'Amato.

Atlas was also involved in the careers of several other world champs, like Michael Moorer, Shannon Briggs, Tim Bradley and Donny Lalonde. He said he got his recognizable facial scar, and the resulting 400 stitches, from being slashed by a knife in a street fight in the late 1970s.

In 1962 former world champion Rocco Francis Marchegiano, aka Rocky Marciano, shows off the rugged, ring-worn fists that scored 43 knockouts in 49 ring victories, an almost 90 percent KO ratio. This is one of the greatest boxing photos ever taken, those fusts look frightening, like balls of iron attached to the end of his arms.

Philadelphia Pal Moore was one of five brothers fighting out of Philadelphia, others being - Willie, Reddy, Frankie and Al; He was not yet sixteen years of age when he began fighting in 1907; Right away, he fought many contests each year and was an experienced fighter even as a teen; Not a power hitter, he was a talented, scrappy boxer who tangled with the best. Fighting in during a period in which "No Decision" bouts were the norm, newspaper reports indicate that he defeated many top men and future champions such as - Jem Driscoll, Oscar "Battling" Nelson, Johnny Dundee, Jimmy Walsh, Young Dyson, Eddie Smith, Julius "Yankee" Schwartz, Joe "Kid" Coster, Knockout Brown, Al Delmont, Tommy O'Toole, Matty Baldwin, Robert "Bert" Keyes, "Young" Sammy Smith, Jack Redmond, "Fighting" Dick Hyland and "Young" Abe Brown. Moore was inducted into the Pennsylvania Boxing Hall of Fame in 1973.

Love that photo of Philadelphia Pal Moore above, it was taken on a rooftop. He looks so young, he started fighting when he was still a kid, Moore was a hardened battler that ducked nobody.

From Chaitaly on Facebook, and brilliantly written I might add:

Ken Norton’s greatness has never been the kind that fits neatly into a highlight reel. It’s not the type that comes wrapped in a bow, or framed by an unbeaten record, or built on an iron jaw that can swallow punches like pebbles tossed into a lake. His legacy is messier, more human, stitched together from courage, flawed brilliance, and the stubbornness of a man who refused to accept what the sport told him he couldn’t be.

And maybe that’s why people still argue about him. How can a fighter who was stopped so violently in some bouts still be spoken of as one of the greats? How can someone who folded quickly under George Foreman’s hurricane fists, or later under Gerry Cooney’s sledgehammer lefts, be placed among the elite?

It starts with a truth fans don’t always like to admit: a chin is mostly a genetic lottery ticket. You draw a strong one or a fragile one, and there isn’t much you can do to change it. Norton was born with everything a heavyweight hoped for—size, range, athleticism, durability of body—but not that one mysterious piece of anatomy that lets you stay conscious when lightning hits your jaw. The heavyweight division is cruel that way. A man can train for years, master technique, build muscle on muscle…and still fall the instant a punch lands just right.

There’s no shame in being knocked out by the monsters Norton faced. Earnie Shavers didn’t punch like a normal human; he punched like the earth itself buckled in his gloves. George Foreman at his peak looked like a man trying to uproot trees with every swing. And Gerry Cooney—well, by the time Cooney found Norton in 1981, the man was closer to middle-aged than his prime, his reflexes dulled, his body tired from a decade of trench warfare. Getting blasted out by them was no indictment of his heart or skill. Not surviving those storms only proved he was made of mortal stuff.

What Norton did control, though, was how he fought. He was smart enough, honest enough with himself, to adopt that cross-armed defense—awkward, unusual, but perfect for someone who needed an extra layer between his jaw and the chaos in front of him. Archie Moore made it famous. A few modern fighters, like Floyd Mayweather, use versions of it for the same reason: to hide the chin behind the shoulder, the glove, anything. Because even the most gifted technician knows there are forces in the ring that can erase all your skills in a second.

Picture Mayweather stepping in against the long, whip-cracking power of Thomas Hearns in his prime. That shoulder roll would suddenly feel a lot thinner. And that’s the point. At heavyweight in the 1970s, nearly every opponent was a Hearns—bigger, heavier, throwing punches that sounded like axes hitting frozen wood. Surviving in that era wasn’t just about skill; it required a kind of bravery that borders on reckless.

And that’s where Norton’s legacy really begins.

Because when the lights were brightest and the stakes highest, he showed a dimension only the great ones possess. He met Muhammad Ali three times, and in the first encounter he didn’t just beat him—he broke Ali’s jaw and outboxed him with a confidence that stunned the world. Their trilogy became one of the sport’s great chess matches: Norton’s awkward rhythm, that crab-like guard, the constant pressure, the looping right hand that always seemed to sneak through.

You can argue forever about who really won the third fight, but what stays with you isn’t the scorecard—it’s how Norton stood there, round after round, forcing the greatest heavyweight artist of all time to fight for every inch. There’s a famous line from a commentator in that era: “Going the distance with Ali is a master’s degree in boxing.” Norton didn’t just go the distance—he made Ali work harder than almost anyone ever had.

That’s why people still speak his name with respect. Because greatness in boxing isn’t just about who never fell. Sometimes it’s about the man who rose anyway, who stepped into the ring knowing his own vulnerabilities and still dared to test himself against giants. Kenny Norton wasn’t perfect. But greatness is rarely born from perfection.

More often, it’s carved from the flaws a man refuses to hide from.

Comments

PART II

Nothing was simpler for Liston to fathom than the world between the ropes—step, jab, hook—and nothing was more unyielding than the secrets of living outside them. He was a mob fighter right out of prison. One of his managers, Frank Mitchell, the publisher of the St. Louis .Argus, who had been arrested numerous times on suspicion of gambling, was a known front for John Vitale, St. Louis's reigning hoodlum. Vitale had tics to organized crime's two most notorious boxing manipulators: Frankie Carbo and Carbo's lieutenant, Frank (Blinky) Palermo, who controlled mob fighters out of Philadelphia. Vitale was in the construction business (among others), and when Liston was fighting, one of his jobs was cracking heads and keeping black laborers in line. Liston always publicly denied this, but years later he confided his role to one of his closest Las Vegas friends, Davey Pearl, a boxing referee. "He told me that when he was in St. Louis, he worked as a labor goon." says Pearl, "breaking up strikes."

Not pleased with the company Liston was keeping—one of his pals was 385-pound Barney Baker, a reputed head cracker for the Teamsters—the St. Louis police kept stopping Liston, on sight and without cause, until, on May 5, 1956, 3½ years after his release from prison, Liston assaulted a St. Louis policeman, took his gun, left the cop lying in an alley and hid the weapon at a sister's house. The officer suffered a broken knee and gashed face. The following December, Liston began serving nine months in the city workhouse.

Soon after his release Liston had his second run-in with a St. Louis cop. The officer had creased Liston's skull with a nightstick, and two weeks later the fighter returned the favor by depositing the fellow headfirst in a trash can. Liston then tied St. Louis for Philadelphia, where Palermo installed one of his pals, Joseph (Pep) Barone, as Liston's manager, and Liston at once began fighting the biggest toughs in the division. He stopped Bethea, who spit out seven teeth, in the first round. Valdes fell in three, and so did Williams. Harris swooned in one, and Policy fell like a tree in three. Eddie Machen ran for 12 rounds but lost the decision. Albert Westphal keeled in one. Now Liston had one final fight to win. Only Patterson stood between him and the title.

Whether or not Patterson should deign to fight the ex-con led, at the time, to a weighty moral debate among the nation's reigning sages of sport. What sharpened the lines were Liston's recurring problems with the law in Philadelphia, including a variety of charges stemming from a June 1961 incident in Fairmount Park. Liston and a companion had been arrested for stopping a female motorist after dark and shining a light in her car. All charges, including impersonating a police officer, were eventually dropped. A month before, Liston had been brought in for loitering on a street corner. That charge too was dropped. More damaging were revelations that he was, indeed, a mob fighter, with a labor goon's history. In 1960, when Liston was the No. 1 heavyweight contender, testimony before a U.S. Senate subcommittee probing underworld control of boxing had revealed that Carbo and Palermo together owned a majority interest in him. Of this, Liston said, he knew nothing. "Pep Barone handles me," he said. "Do you think that people like [Carbo and Palermo] ought to remain in the sport of boxing?" asked the committee chairman, Tennessee senator Estes Kefauver.

"I wouldn't pass judgment on no one," Liston replied. "I haven't been perfect myself."

In an act of public cleansing after the Fairmount Park incident, Liston spent three months living in a house belonging to the Loyola Catholic Church in Denver, where he had met Father Edward Murphy, a Jesuit priest, while training to fight Folley in 1960. Murphy, who died in 1975, became Liston's spiritual counselor and teacher. "Murph gave him a house to live in and tried to get him to stop drinking," Father Thomas Kelly, one of Murphy's closest friends, recalls. "That was his biggest problem. You could smell him in the mornings. Oh, poor Sonny. He was just an accident waiting to happen. Murph used to say, 'Pray for the poor bastard.' "

But even Liston's sojourn in Denver didn't still the debate over his worthiness to fight for the title. In this bout between good and evil, the clearest voice belonged to New York Herald-Tribune columnist Red Smith: "Should a man with a record of violent crime be given a chance to become champion of the world? Is America less sinful today than in 1853 when John Morrissey, a saloon brawler and political head-breaker out of Troy, N.Y., fought Yankee Sullivan, lamister from the Australian penal colony in Botany Bay? In our time, hoodlums have held championships with distinction. Boxing may be purer since their departure; it is not healthier." Since he could not read, Liston missed many pearls, but friends read scores of columns to him. When Bar-one was under fire for his mob ties, Liston quipped, "I got to get me a manager that's not hot—like Estes Kefauver." Instead, he got George Katz, who quickly came to appreciate Liston's droll sense of humor. Katz managed Liston for 10% of his purses, and as the two sat in court at Liston's hearing for the Fairmount Park incident, Liston leaned over to Katz and said, "If I get time, you're entitled to 10 percent of it."

Liston was far from the sullen, insensitive brute of the popular imagination. Liston and McKinney

would take long walks between workouts, and during them Liston would recite the complete dialogue and sound effects of the comedy routines of black comedians like Pigmeat Markham and Redd Foxx. "He could imitate what he heard, down to creaking doors and women's voices," says McKinney. "It was hilarious hearing him do falsetto."

Liston also fabricated quaint metaphors to describe phenomena ranging from brain damage to the effects of his jab: "The middle of a fighter's forehead is like a dog's tail. Cut off the tail and the dog goes all which way 'cause he ain't got no more balance, It's the same with a fighter's forehead."

He lectured occasionally on the unconscious, though not in the Freudian sense. Setting the knuckles of one fist into the grooves between the knuckles of the other fist, he would explain: "Sec, the different parts of the brain set in little cups like this. When you get hit a terrible shot—pop!—the brain flops out of them cups and you're knocked out. Then the brain settles back in the cups and you come to. But after this happens enough times, or sometimes even once if the shot's hard enough, the brain don't settle back right in them cups, and that's when you start needing other people to help you get around.

So it was that Liston vowed to hit Patterson on the dog's tail until his brain Hopped out of its cups. Actually, he missed the tail and hit the chin. Patterson was gone. Liston had trained to the minute, and he was a better fighter that night than he would ever be again. And what had it gotten him? Obviously, nothing in his life had changed. He left Philadelphia after he won the title, because he believed he was being harassed by the police of Fairmount Park, through which he had to drive to get from the gym to his home. At one point he was stopped for "driving too slow" through the park. That did it. In 1963 he moved to Denver, where he announced, "I'd rather be a lamppost in Denver than the mayor of Philadelphia." At times, in fact, things were not much better in the Rockies. "For a while the Denver police pulled him over every day," says Ray Schoeninger, a former Liston sparring partner. "They must have stopped him 100 times outside City Park. He'd run on the golf course, and as he left in his car, they'd stop him. Twenty-five days in a row. Same two cops. They thought it was a big joke. It made me ashamed of being a Denver native. Sad they never let him live in peace."

Liston's disputes were not always with the police. After he won the title, he walked into the dining room of the Beverly Rodeo Hotel in Hollywood and approached the table at which former rumrunner Moe Dalitz, head of the Desert Inn in Las Vegas and a boss of the old Cleveland mob, was eating. The two men spoke. Liston made a fist and cocked it. Speaking very distinctly, Dalitz said, "If you hit me, nigger, you better kill me. Because if you don't. I'll make one telephone call, and you'll be dead in 24 hours." Liston wheeled and left. The police and Dalitz were hardly Liston's only tormentors. There was a new and even more inescapable disturber of his peace: the boisterous Clay. Not that Liston at first took notice. After clubbing Patterson, he took no one seriously. He hardly trained for the rematch in Las Vegas. Clay, who hung around Liston's gym while the champion went through the motions of preparing for Patterson, heckled him relentlessly. Already a minor poet, Clay would yell at Liston, "Sonny is a fatty. I'm gonna whip him like his daddy!" One afternoon he rushed up to Liston, pointed to him and shouted, "He ain't whipped nobody! Who's he whipped?" Liston, sitting down, patted a leg and said, "Little boy, come sit in my lap." But Clay wouldn't sit; he was too busy running around and bellowing. "The beast is on the run!"

Liston spotted Clay one day in the Thunderbird Casino, walked up behind him and tapped him on the shoulder. Clay turned, and Liston cuffed him hard with the back of his hand. The place was silent. Young Clay looked frightened. "What you do that for?" he said.

" 'Cause you're too——fresh," Liston said. As he headed out of the casino, he said, "I got the punk's heart now."

That incident would be decisive in determining the outcome of the first Liston-Clay fight, seven months later. "Sonny had no respect for Clay after that," McKinney says. "Sonny thought all he had to do was take off his robe and Clay would faint. He made this colossal misjudgment. He didn't train at all."

If he had no respect for Clay, Liston was like a child around the radio hero of his boyhood, Joe Louis. When George Lois, then the art director at Esquire, decided to try the black-Santa cover, he asked his friend Louis to approach Liston. Liston grudgingly agreed to do the shoot in Las Vegas. Photographer Carl Fischer snapped one photograph, whereupon Liston rose, took off the cap and said, "That's it." He started out the door. Lois grabbed Liston's arm. The fighter stopped and stared at the art director. "I let his arm go," Lois recalls.

While Liston returned to the craps

tables, Lois was in a panic. "One picture!" Lois says. "You need to take 50, 100 pictures to make sure you get it right." He ran to Louis, who understood Lois's dilemma. Louis found Liston shooting craps, walked up behind him, reached up, grabbed him by an car and marched him out of the casino. Bent over like a puppy on a leash, Liston followed Louis to the elevator, with Louis muttering, "Come on, git!" The cover shoot resumed.

A few months later, of course, Clay handled Liston almost as easily. Liston stalked and chased, but Clay was too quick and too fit for him. By the end of the third round Liston knew that his title was in peril, and he grew desperate. One of Liston's trainers, Joe Pollino, confessed to McKinney years later that Liston ordered him to rub an astringent compound on his gloves before the fourth round. Pollino complied. Liston shoved his gloves into Clay's face in the fourth, and the challenger's eyes began burning and tearing so severely that he could not see. In his corner, before the fifth round, Clay told his handlers that he could not go on. His trainer, Angelo Dundee, had to literally push him into the ring. Moving backward faster than Liston moved forward, Clay ducked and dodged as Liston lunged after him. He survived the round.

By the sixth Clay could sec clearly again, and as he danced and jabbed, hitting Liston at will, the champion appeared to age three years in three minutes. At the end of that round, bleeding and exhausted, he could foresee his humiliating end. His left shoulder had been injured—he could no longer throw an effective punch with it—and so he stayed on his stool, just sat there at the bell to start Round 7.

There were cries that Liston had thrown the fight. That night Conrad, Liston's publicist, went to see him in his room, where Liston was sitting in bed, drinking.

"What are they saying about the fight?" Liston asked.

"That you took a dive," said Conrad.

Liston raged. "Me? Sell my title? Those dirty bastards!" He threw his glass and shattered it against the wall.

The charges of a fix in that fight were nothing compared with what would be said about the rematch, in Lewiston, Maine, during which Liston solidified his place in boxing history. Ali, as the young champion was now widely called, threw one blow, an overhand right so dubious that it became known as the Phantom Punch, and suddenly Liston was on his back. The crowd came to its feet in anger, yelling. "Fake! Fake!"

Ali looked down at the fallen Liston, cocked a fist and screamed at him, "Get up and fight, sucker! Get up and fight!"

There was chaos. Referee Joe Walcott, having vainly tried to push Ali to a neutral corner, did not start a count, and Liston lay there unwilling to rise. "Clay caught me cold," Liston would recall. "Anybody can get caught in the first round, before you work up a sweat. Clay stood over me. I never blacked out. But I wasn't gonna get up, either, not with him standing over me. Sec, you can't get up without putting one hand on the floor, and so I couldn't protect myself."

The finish was as ugly as a Maine lobster. Walcott finally moved Ali back, and as Liston rose, Walcott wiped off his gloves and stepped away. Ali and Liston resumed fighting. Immediately, Nat Fleischer, editor of The Ring magazine, who was sitting next to the official timer, began shouting for Walcott to stop the fight. Liston had been down for 17 seconds, and Fleischer, who had no actual authority at ringside, thought the fight should have been declared over. Walcott left the two men fighting and walked over to confer with Fleischer. Though he had never even started a count, Walcott then turned back to the fighters and, incredibly, stepped between them to end the fight. "I was never counted out," Liston said later. "I coulda got up right after I was hit."

No one believed him, of course, and even Geraldine had her doubts. Ted King, one of Liston's seconds, recalls her angrily accusing Sonny later that night of going in the water.

"You could have gotten up, and you stayed down!" she cried.

Liston looked pleadingly at King. "Tell her, Teddy," he said. "Tell her I got hit."

Some who were at ringside that night, and others who have studied the films, insist that Ali indeed connected with a shattering right. But Liston's performance in Lewiston has long been perceived as a tank job, and not a convincing one at that. One of Liston's assistant trainers claims that Liston threw the fight for fear of being murdered. King now says that two well-dressed Black Muslims showed up in Maine before the fight—Ali had just become a Muslim—and warned Liston, "You get killed if you win." So, according to King, Liston chose a safer ending. It seems fitting somehow that Liston should spend the last moments of the best years of his life on his back while the crowd showered him with howls of execration. Liston's two losses to Ali ended the short, unhappy reign of the most feared—and the most relentlessly hounded—prizefighter of his time.

Liston never really retired from the ring. After two years of fighting pushovers in Europe, he returned to the U.S. and began a comeback of sorts in 1968. He knocked out all seven of his opponents that year and won three more matches in 1969 before an old sparring partner, Leotis Martin, stopped him in the ninth round of a bout on Dec. 6. That killed any chance at a title shot. On June 29, 1970, he fought Chuck Wepner in Jersey City. Tocco, Liston's old trainer from the early St. Louis days, prepared him for the light against the man known as the Bayonne Bleeder. Listen hammered Wepner with jabs, and in the sixth round Tocco began pleading with the referee to stop the fight. "It was like blood was coming out of a hydrant," says Tocco. The referee stopped the bout in the 10th: Wepner needed 57 stitches to close his face.

That was Liston's last fight, He earned $13,000 for it, but he wound up broke nonetheless. Several weeks earlier, Liston had asked Banker to place a $10,000 bet for him on undefeated heavyweight contender Mac Foster to whip veteran Jerry Quarry. Quarry stopped Foster in the sixth round, and Liston promised Banker he would pay him back after the Wepner fight. When Liston and Banker boarded the flight back to Las Vegas, Liston opened a brown paper bag, carefully counted out $10,000 in small bills and handed the wad to Banker. "He gave the other $3,000 to guys in his corner," Banker said. "That left him with nothing."

In the last weeks of his life Liston was moving with a fast crowd. At one point a Las Vegas sheriff warned Banker, through a mutual friend, to stay away from Liston. "We're looking into a drug deal," said the sheriff. "Liston is getting involved with the wrong people." At about the same time two Las Vegas policemen stopped by the gym and told Tocco that Liston had recently turned up at a house that would be the target of a drug raid. Says Tocco, "For a week the police were parked in a lot across the street, watching when Sonny came and who he left with."

On the night Geraldine found his body, Liston had been dead at least six days, and an autopsy revealed traces of morphine and codeine of a type produced by the breakdown of heroin in the body. His body was so decomposed that tests were inconclusive—officially, he died of lung congestion and heart failure—but circumstantial evidence suggests that he died of a heroin overdose. There were fresh needle marks on one of his arms. An investigating officer, Sergeant Gary Beckwith, found a small amount of marijuana along with heroin and a syringe in the house. Geraldine, Banker and Pearl all say that they had no knowledge of Liston's involvement with drugs, but law enforcement officials say they have reason to believe that Liston was a regular heroin user. Those closest to him may not have known of his drug use. Liston had apparently lived two lives for years.

Pearl was always hearing reports of Liston's drinking binges, but Liston was a teetotaler around Pearl. "I never saw Sonny take a drink." says Pearl. "Ever. And I was with him hundreds of times over the last five years of his life. He'd leave me at night, and the next morning someone would say to me, 'You should have seen your boy, Liston, last night. Was he ever drunk!' I once asked him, 'What is this? You leave me at night and go out and get drunk?' He just looked at me. I never, ever suspected him of doing dope. I'm telling you, I don't think he did."

Some police officials and not a few old friends think that Liston may have been murdered, though they have no way of proving it now. Conrad believed that Liston had become deeply involved in a loan-sharking ring in Las Vegas, as a bill collector, and that he had tried to muscle in for a bigger share of the action. His employers got him drunk. Conrad surmised, took him home and stuck him with a needle. There are police in Las Vegas who say they believe—but are unable to prove—that Liston was the target of a hit ordered by Ash Resnick, an old associate of Liston's with whom he was having a dispute over money. Resnick died in 1989.

Geraldine has trouble comprehending all that talk about heroin or murder. "If he was killed, I don't know who would do it," she says. "If he was doing drugs, he didn't act like he was drugged. Sonny wasn't on dope. He had high blood pressure, and he had been out drinking in late December. As far as I'm concerned, he had a heart attack. Case closed."

There is no persuasive explanation of how Liston died, so the speculation continues.

Liston is buried in Paradise Memorial Gardens, in Las Vegas, directly under the flight path for planes approaching McCarran International Airport. The brass plate on the grave is tarnished now, but the epitaph is clear under his name and the years of his life. It reads simply: A MAN Twenty years ago father Murphy Hew in from Denver to give the eulogy, then went home and wept for an hour before he could compose himself enough to tell Father Kelly about the funeral. "They had the funeral procession down the Strip." Murphy said. "Can you imagine that? People came out of the hotels to watch him pass. They stopped everything. They used him all his life. They were still using him on the way to the cemetery. There he was, another Las Vegas show. God help us."

In the end, it seemed fitting that Liston, after all those years, should finally play to a friendly crowd on the way to his own burial—with a police escort, the most ironic touch of all.

Geraldine remained in Las Vegas for nine years after Sonny died—she was a casino hostess—then returned to St. Louis, where she had met Sonny after his parole, when he was working in a munitions factory. She has never remarried, and today works as a medical technician. "He was a great guy, great with me, great with kids, a gentle man," says Geraldine.

With Geraldine gone from Las Vegas, few visit Sonny's grave anymore. Every couple of minutes a plane roars over, shaking the earth and rattling the broken plastic flowers that someone placed in the metal urn atop his headstone. "Every once in a while someone comes by and asks to see where he's buried, "says a cemetery worker. "But not many anymore. Not often."

In boxing, if you want to get a good sense of what a fighter was like in the ring, his power, skills, etc., you ask the opponents he faced. It's interesting listening to people talk about Sonny Liston, you can get a good sense of what it was like to be in the ring with him. Chuck Wepner fought Liston, Foreman, and Ali and he said that Liston had the best jab, was the strongest, and the best puncher of the three.

Chuck Wepner:

BEST JAB

Sonny Liston: He threw it right from the shoulder, it was short, and he had everything behind it. That’s why it was a hard punch to get away from. I really didn’t get away from it too good. I wound up with 71 stitches, a broken nose and broken left cheekbone. Most of it was from the jab.

STRONGEST

Liston: That would have to be Sonny Liston or George Foreman. I was a brawler, I was an intimidator, I tried to go out and push a guy around, rough ’em up early. Sonny and George, as soon you banged into them, it was like banging into a brick wall. They didn’t move. I’d say Liston in his prime.

BEST PUNCHER

Liston: It hurts if anybody hits you. I could always take it, absorb it and come back, but with Liston, after you got hit by him, you were very weary to make that move again. We trained to stick a jab and move with Liston, but he stayed right on your chest, throwing punches. Not like Ali, who would hit you and get out. George was powerful, too. George cut me open pretty early in the fight. I always thought it was a headbutt, but it was an accidental head clash. He did cut me open, and they stopped it after the third round. Probably Sonny Liston was the best puncher.

Of course Wepner wasn't lying when he said Liston gave him 71 stitches, broke his nose and cheekbone. He left Wepner in bad shape.

Personally, my favorite Sonny Liston fights were his fights with Cleveland "Big Cat" Williams. He fought Williams twice, both fights combined only lasted five rounds. Like Sonny Liston, Cleveland Williams was a murderous puncher himself, and he decided he was going to just go for broke and try to take Liston out in both fights. What we got was two apocalyptic shootouts.

Recalling The Sonny Liston Vs. Cleveland Williams Wars

By James Slater - 01/21/2020

No-one knows for sure when heavyweight king Charles “Sonny” Liston was born, therefore we don’t know how old Liston was when he was at his absolute peak. But there is one fight that stands out as the peak performance of Liston’s entire career: a fight that saw Liston show some truly ferocious punching prowess, a rock of a chin, great speed of hand, superb accuracy and a truly unquenchable thirst for battle. This primed and peaked performance came in March of 1960, as Liston, then (officially) aged 30 or 32 (depending on which official record you go by; really there being no such thing in existence) met fellow monster puncher, the equally carved from granite Cleveland Williams. It’s mindboggling to think how these two superb, and avoided, fighting machines were matched together twice, inside 11 months. Today, both men, with good connections and even better protection (as Muhammad Ali might say) would have been kept apart, at least until one of them won a world title (as both would undoubtedly do today). But Liston and Williams fought in a different time, a far tougher time. And so they went to war, first in April of 1959, and then again in March of the following year. Williams, who was born in 1933, was 47-3 at the time of his return rumble with Liston (the three losses coming against Sylvester Jones, on points in 1953, Bob Satterfield, by KO in 1954, and to Liston in 1959). Williams enjoyed a one-inch height advantage over Sonny, while Liston had the edge in reach at 84” to 80”. In their first encounter was held at Miami Beach, with Liston then being 27-1 (the loss coming on points to Marty Marshall in 1954, later avenged) and the crowd had been treated to a quite magnificent and highly entertaining three-round slugfest. Williams had success early, hitting and hurting a slow-starting Liston; bloodying the older man’s nose. But Liston, a fighter with the single best “poker face” imaginable, never let on if he was in fact hurt. Liston poured it on towards the end of round-two, and then, sensing his man was hurt, decked Williams twice to get the stoppage in the third. It was a great win for Liston; a man who, like Williams, had real trouble finding quality opposition. Three fights, three wins and 11 months later, Liston faced Williams a second time. The return took place in Houston, Texas, and another violent affair unfolded. A fairly even opening round went by, but no-one was expecting the action to last too long. And it didn’t. A great second-round saw both men land with power punches, but once again Liston would not be denied. Sonny had to take a fierce left hook from Williams, however, along with a burst of hurtful follow up blows which had him stuck in a corner, before retaliating with blistering shots of his own. Then, after three consecutive lefts from Williams, Liston landed a cracking overhand right , followed by another right hand that landed flush, and then a perfect left hook to the jaw that dropped his man heavily. Showing great bravery, the badly battered fighter got up at eight – only to be met by a ferocious Liston who was coming to finish him off. With the courageous Williams stuck in the same corner that he himself had just been forced into, Sonny teed off on his wounded target. Blow after blow landed, until Williams slid down the ropes to the floor. He was grimacing in pain as he did so. Somehow, in a truly amazing display of guts, Williams pulled himself upright once more. But the referee had seen enough and he stopped the onrushing Liston in his tracks, putting a stop to the brutal fight. Liston had looked absolutely awesome. As near to unbeatable as anyone could imagine a fighter to look. Indeed, this was the peak Sonny Liston – the most terrifying, the fastest, hardest hitting and just plain best heavyweight on the planet at the time.

This shot is from the first Sonny Liston-Cleveland Williams fight, great shot, you can see how brutal it was, Liston's nose is broken and bleeding. Williams was a murderous puncher and he caught Liston with some thunderous shots. But this fight really demonstrated what a nightmare Liston was, Williams hit him with the kitchen sink and it just didn't matter, Sonny still smashed him.

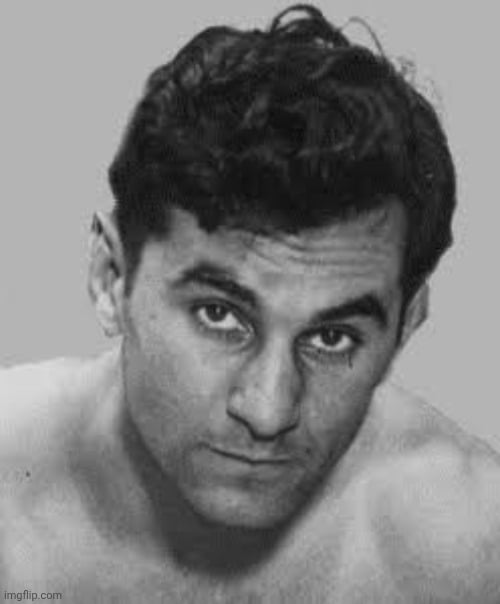

Floyd Patterson was an all-time great and he fought Sonny Liston twice, both fights combined lasted a total of two rounds, Sonny Liston needed just 126 seconds to take the heavyweight title from Patterson in 1962 at Comiskey Park. About halfway through the first round, Liston hurt Patterson with a right uppercut. Liston followed with a series of punches, ending with a left hook, that dropped Patterson. He made it to his feet but was unable to beat the referee's count of ten. The contract stated that if Liston won, he would have to give Patterson a rematch within a year. The rematch between Liston and Patterson was almost a carbon copy of the first fight, this time Liston needed only 130 seconds. Liston knocked Patterson down three times, with the fight ending at 2:10 in the first round.

The Cuban heavyweight Nino Valdez was darn good fighter as well, had good boxing skills and power. Liston took him out in 47 seconds.

Zora Folley was a great ring technician, I profiled him earlier in the thread. He lasted three rounds against Liston.

Time for a music break, one of the greatest songs ever made.

Sonny Liston watches as Albert Westphal sinks to the floor unconscious after a rough 1-2 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1961. Westphal would take minutes to regain consciousness.

Sonny Liston's fists were huge, the size of a softball. I mean, my God, can you just imagine being hit full force by Liston.

This is what it was like being hit by those fists. Sonny Liston may have been legit the most feared fighter in the history of boxing, even moreso than Mike Tyson, and watching this video, it's easy to see why. This is the brutal destruction of Sonny Liston.

Let's get a look at some stuff from Liston's career.

This is one of those great boxing photos, the intimidation of Sonny Liston.

Liston had the greatest jab in heavyweight history.

Liston after reaching the mountain top and becoming the world heavyweight champion.

Liston training with George Foreman by his side, George Foreman and Sonny Liston had a complex relationship of mentor and mentee, with Liston acting as a formidable sparring partner and a dark mentor to the younger Foreman. Foreman considered sparring with Liston the most dangerous thing he had ever done, and said Liston taught him the importance of the jab and how to back opponents up. Foreman adopted Liston's intimidating stare and fierce persona, which helped him develop his "Bad George" image, though he later found a more spiritual path.

Sonny Liston with Jack Nicholson.

One last look at the destruction of Sonny Liston.

Liston hitting the speed bag.

Liston training on a backroad for Patterson.

The great Sonny Liston.

One last photo of Sonny Liston, this is one of my favorite boxing photos of all-time, Liston with the kid by his side. It's just a sick image.