“I knew I had tools and I knew I had power but I also understood that once that bell rings, it’s just man against man. And most of the time, it comes down to who wants it more, and who trained the hardest.

When someone hits me, I don’t panic I think:

‘That’s fine… now feel one of mine.’”

Up next, Rocky Kansas, world lightweight champion that fought from 1911 to 1932. Rocky Kansas turned professional in 1911, and his early career was marked by consistency. He lost only two official decisions in his first 75 fights—a testament to his skill and determination. Known for his tenacity and relentless fighting style, Kansas quickly became one of the most respected athletes in boxing . Honest to god, he was one of the most relentless, tenacious, and determined men to ever enter a boxing ring. Over the course of his hall of fame career, he beat Freddie Welsh, Lew Tendler, Jimmy Duffy x2, Johnny Dundee x2, Johnny Kilbane, Ritchie Mitchell x2, Jack Bernstein, Charley White, Frankie Britt, Ad Wolgast and Jimmy Goodrich. That's the resume of an all-time great. He shared the same era as the great Benny Leonard, and tried like hell, four times, to get the lightweight title away from Leonard, but Leonard was special. But like I said, Rocky Kansas was one of the most tenacious and determined men to ever enter a boxing ring and he would not be denied entry into the throne room of the lightweight gods. Born Rocco Tozzo on April 21, 1895 in Buffalo, NY. A former newsboy, he started using the name Rocky Kansas 1911 when a ring announcer mistakenly introduced him under that name. Known as “Little Hercules,” the 5’2” Kansas was a stocky, powerful brawler with a sturdy build. One of the top lightweights of his era, he met Benny Leonard four times between 1916-1922 (ND 10, ND 12, L 15, KO by 8). Following Leonard’s retirement as champion in 1925, Buffalo’s Jimmy Goodrich ascended to the title. In front of 12,000 fans at Buffalo’s Broadway Auditorium on December 7, 1925, Kansas, in his 160th bout and 15 years into his career, defeated Goodrich to become new champion. His reign was brief, dropping the strap to Sammy Mandell in 1926. He promptly retired, but engaged in one comeback fight in 1932 (L 6) before retiring for good.

Rocky Kansas was one of the top lightweights of his era, but unfortunately he shared that era with Benny Leonard, who is arguably the greatest lightweight in the history of the sport. Kansas couldn't get past Leonard, not many people could, but Kansas wasn't the type of guy to give up, like I said, he was a tenacious son of a gun. He wasn't going to stop until he reached the mountaintop.

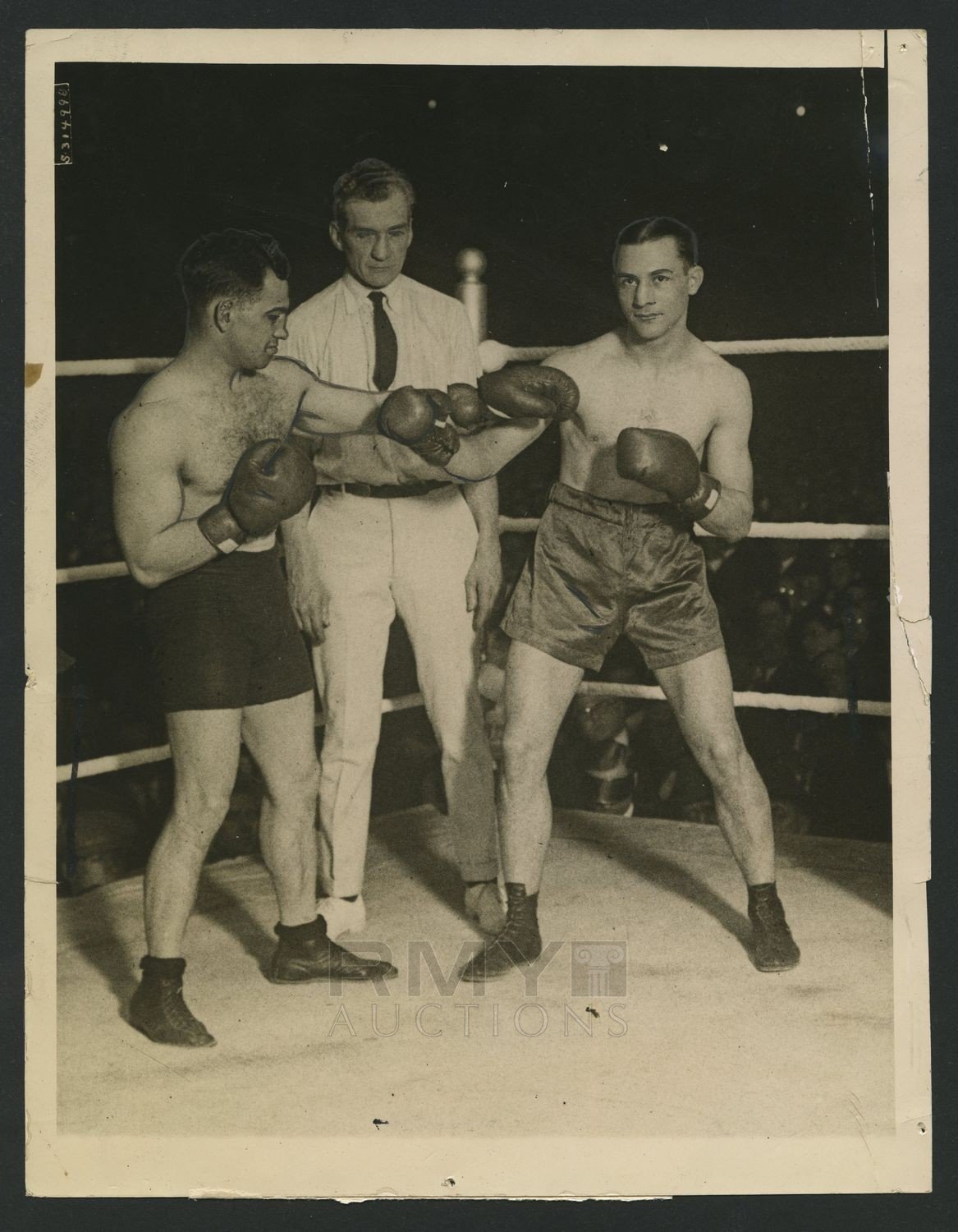

Rocky Kansas (left) and Benny Leonard face off in front of the camera

From boxing forum 24, Matt McGrain on Rocky Kansas:

"Hard to hard to imagine the frustration of a fighter doomed to share an era with the great Benny Leonard. All great fighters torture the ambitions of their peers but fewer fighters can have blunted more dreams in a single division than the great Leonard. Rocky Kansas can number himself among them.

The two first shared the ring in February of 1916 with Kansas fresh from the featherweight division and Leonard not yet the fistic god he would become. Nevertheless, Leonard was dominant and Rocky, who fought gamely, “wilted every time” Leonard “crushed over his right.” The two wouldn’t meet again until 1921, an absolute age in the parlance of the time, Leonard’s title on the line. Despite Rocky’s strong finish, Leonard was once again triumphant. But Rocky just wouldn’t go away. He went unbeaten in nine, including a victory over Lew Tendler, forcing Leonard to give him a second title shot in their third fight. “He is strong, willing and has plenty of courage,” noted the Quebec Telegraph. “He likes to fight. That makes him dangerous.”

He was dangerous enough to go six rounds without losing one to the great man, winning the first four in some accounts; thereafter, the champion ran away with the fight and Rocky was sent spinning out of title contention once more. But such was the impression that he had made with those opening eighteen minutes that two wins later he was back in the ring with Leonard once more.

This time Leonard crushed him, beating him into submission in just eight rounds. It seemed that Rocky’s title aspirations were finally at an end. What are they made of, these boys who keep coming back for more, who cannot be turned away? When Benny Leonard retired in 1925, Jimmy Goodrich, a fine fighter, became the champion. And Rocky was still winning. He had been in the ring for fourteen hard years but against Goodrich, he found himself with one last chance.

Associated Press reported a near universal feeling at ringside that he would once again fade, that he could not possibly sustain the savage pace he set at the bell; that feeling was born out. But this time, he did not wilt. Kansas split lightweight series with the likes of Johnny Dundee and Jack Bernstein but when his last best chance presented itself, he took it. The veteran threw the championship aloft at the bell. I love Rocky’s narrative. He was a lion who had the terrible luck to share a cage with a tiger who, despite all those maulings, had enough to see off the cub they tried to move on to his territory."

Leonard and Rocky Kansas would fight four times, and although Leonard would win all of those bouts, it was fight #3 which was the one that Kansas almost got Leonard. The fight took place at Madison Square Garden, New York. Kansas was one hell of a body puncher, he was one of those "damn the torpedoes" fighters, who threw caution to the wind and just aggressively went for it, I love those types of fighters, and that's exactly what he did against Leonard in their third encounter.

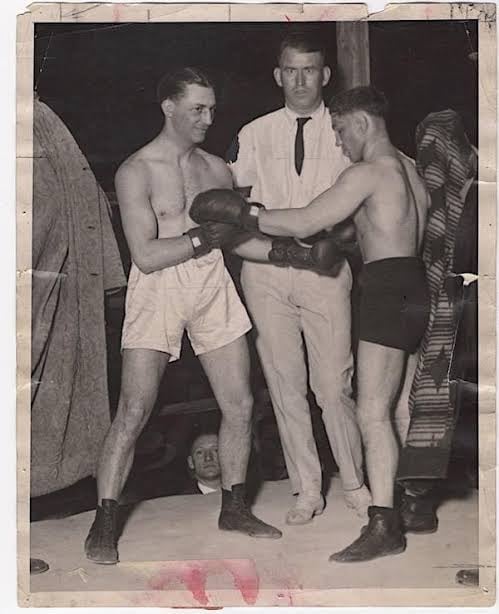

Benny Leonard (left) and Rocky Kansas face off before their third encounter

In the opening rounds, Kansas rushed in and ripped into Leonard’s body with wild punches, as Leonard jabbed him repeatedly with a straight left managing his distance most effectively.

But Kansas kept a vicious pace by crowding and clinching Leonard, who started to bleed from the nose. The crowd began to wonder… was this to be a Leonard defeat?

Midway through the fight, Kansas turned southpaw, trying to confuse the champion.

Leonard would maintain his superior skills and in round eleven executed a perfect short right hand to the jaw that dropped Kansas.

The bout would go the distance, 15 rounds, with Leonard winning and retaining his title.

On December 7th, 1925, after 160 grueling ring wars, Rocky Kansas finally reached the top when he defeated Jimmy Goodrich for the lightweight title. I admire the hell out of Kansas, he had a few setbacks in his career, and a lot of fighters would have left the sport, quit, tucked their tail between their legs and ran away. But Rocky Kansas wouldn't go away, when the sport knocked him down he always got back up and kept fighting until he achieved his dream, he would not be denied. That's what this sport is about, that's what life is about. He was the definition of a fighter. Here are two reports of the fight, the first one from TIME magazine in 1925, and the second from The New York Times in 1925.

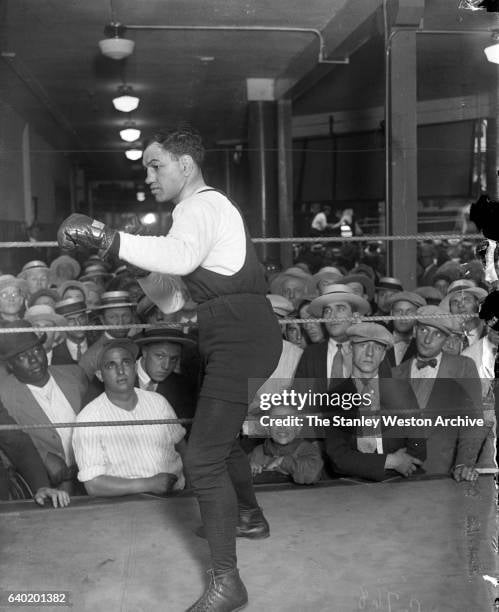

Onlookers watch as Rocky Kansas trains

Sport: Goodrich v. Kansas

2 minute read

TIME

December 21, 1925

Almost all men—from the strong boy who can bite pieces out of a crowbar, to the grubbiest, most dissipated little street sheik—believe that they secrete in their right arms a power that will maim and devastate. Some go through life without ever suffering a disillusion on this score; others have their prayer, “Just gimme a sock at ’em,” gratified, but administer the sock only to find that it has small effect. It lands fearfully on the point of a jaw, and the recipient smiles and shakes his head as if a drop of water had landed on him. This is usually enough to discourage most sockers. In Buffalo last week, it discouraged Jimmy Goodrich, who was at the moment lightweight champion of the world. He had just socked Rocky Kansas, challenger, flush on the button. It was the middle of the second round. Throughout the first, Rocky (a 133-pound battler, battered and be-cauliflowered by innumerable brawls) had come plunging in at a pace that would surely be impossible for him to keep up for 15 rounds. Goodrich waited his chance. Kansas was standing off to loop a left to the head, when he sent across his sock. Wham! With all the leverage of his springy body behind it, his right fist encountered the other’s jaw. Rocky did not waver. Oof! Again the big right-hand sock. Rocky came tearing in. … He was flogging Goodrich’s red ribs when the gong clanged for the end of the 15th round and the referee stepped forward to indicate that he—Rocky (“Bleeding”) Kansas—was the world’s new lightweight champion.

Dec. 8, 1925

GOODRICH IS BEATEN; KANSAS WINS TITLE; Captures World's Lightweight Crown on Decision in 15 Rounds in Buffalo. LOSER STAGES GAME RALLY Takes Last 2 Rounds, but Fails to Overcome Challenger's Overwhelming Lead. VICTORY A POPULAR ONE 10,000 Pay $35,000, Record Sum, to Set City's First Lightweight Title Bout in 23 Years.

BUFFALO, N. Y., Dec. 7.—A new lightweight champion attained the heights here tonight when Rocky Kansas, 'battle-scarred hero of many glorious ring encounters, pounded his way to victory over Jimmy Goodrich, his local rival, and qualified for recognition by the State Athletic Commission as the world's champion. Through a desperate fifteen-round bout Kansas battered away at Goodrich in a surprising attack, and when the final bell clanged on the contest the Italian veteran had an overwhelming margin over his rival on points. Judges George Partrick and Thomas Flynn, with referee Jim Crowley, rendered the verdict which made Kansas champion, and it must have been a unanimous decision, for in his victory Kansas left no room for doubt as to his superiority. Kansas carried off nine of the fifteen rounds, raking Goodrich with a two-fisted fire to the body which had Jimmy weary and sore, and an assault to the face and head which had Goodrich a crimson-flecked gladiator through the greater part of the bout. In three rounds Goodrich held his Italian rival even. These were the second, eighth and thirteenth. In the ninth round, Goodrich won the honors and a desperate rally in the closing two sessions gave Goodrich the fourteenth and fifteenth rounds. But in every other round Goodrich was soundly beaten-was battered convincingly by Kansas in a methodical attack for which Goodrich had no successful counter.

Finish Thrills Crowd.

Goodrich's rally through the closing two rounds thrilled the crowd, which was noticeably pro-Kansas. It came as the climax to a desperate battle which made local ring history. More than 10,000 fight fans, who paid $35,000, a record gate for Buffalo, jammed the Broadway Auditorium, where the battle was held under the auspices of the Queensberry A. C. This was the first lightweight championship bout in Buffalo in twenty-three long years. In the last title struggle among lightweights, Joe Gans, "The Old Master, knocked out Frank Erne, local pride, in a round. That was back in 1902. Shortly after Erne had beaten Kid Lavigne for the title. Tonight Buffalo had to celebrate a winner, for the two lads fighting for the title are natives. The town tonight is burning red torches and parading and celebrating along Main Street over the victory of Kansas, for he entered the ring with the crowd cheering him in greater volume than it did Goodrich. His was a popular victory. The rally of Goodrich was the dying gasp of a beaten gladiator. He must have sensed that the decision was to go against him, for in the closing two sessions he let fly with everything he had, fighting desperately and furiously. Goodrich bent his efforts on a bid for a knockout. He tried and tried and tried with his right for the jaw, hopeful until the end that he would connect with a punch which would avert disaster for him. He landed with grazing blows several times, and occasionally managed to nick the Italian with a right to the jaw which carried enough power to send Rocky backward on his heels.

Rocky Only Smiles.

But Kansas only smiled at Goodrich's efforts, and smiled more broadly when Goodrich managed to nick him. Then he would tear in, as was his custom throughout the bout, and simply overwhelm Goodrich with his attack. Goodrich's was a great effort to save his position as successor to Benny Leonard. It was, moreover, a thrilling bid in Its very desperation, but it failed dismally. Kansas won the title and thereby knocked Goodrich out of the Christmas Fund bout in Madison Square Garden on Dec. 23 simply because he was the stronger ringman and enjoyed a wider experience than Goodrich. He swept onward in a sustained offensive from the start and won the first, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, tenth, eleventh and twelfth rounds by margins wide enough to convince everybody at the bout that he was the master of Goodrich. Kansas survived a majority thought he would collapse. It was expected that he would surprise Goodrich with a fiery early assault, but few expected he would be able, after fourteen years of ring service and at 30 years of age, to sustain this pace over fifteen rounds. That he did is a tribute to his remarkable store of stamina and explains in great measure the result. The fight held no knock-downs. There was not even an indication of a knock- down, although in the first round Goodrich sent Kansas off balance to his haunches with a left jab and push. In the latter rounds Jimmy rocked Kansas several times with crushing rights to the head and jaw. It was, however, a desperate battle, furiously waged. neither asking nor giving quarter. each pressing for an advantage every second of the way.

In Goodrich's Eye Cut.

Kansas fought methodically throughout. He went on the offensive with the first round and save for the late rounds, when Goodrich in desperation assumed the offensive, the Italian showed the way. Beaten in the first round, Goodrich came back and in a spirited recovery held his own with Kansas in the second. Through the next five rounds, however, Kansas had all the better of the milling, outboxing Goodrich at long range, and outhitting Jimmy at close quarters. Goodrich repeatedly tried to stop his rival's rushes with wicked rights to the jaw, but never quite hit the mark. In sporadic outbursts Goodrich would send Kansas's head snapping backward with straight left jabs, but Rocky always came tearing in like a young bull, returning the jabs with jabs of his own. In the fifth round they came together head on and Goodrich emerged from the collision with blood streaming from a long cut over the right eye. It was a handicap through the remainder of the fight for Kansas never lost an opportunity to peck at the injured optic, keeping up a steady crimson flow. In the eighth round Goodrich rallied and held Kansas even. Jimmy fought savagely in the ninth and, although one of Kansas's left hooks knocked some gold bridgework from his mouth, Goodrich battered his rival severely about the head and body and won the round. Through the tenth, Goodrich tried to carry his rally, but the Kansas who was expected by many to weaken grew stronger and took the lead from his rival.

Rocky's furious attack gave him the tenth, eleventh and twelfth rounds, for he fought Goodrich all over the ring. In the thirteenth session Rocky did tire a little and the weary, desperate Goodrich was enabled to come through with a rally which gained him an even break on the honors for the round. . Through the fourteenth and fifteenth rounds Goodrich was all over Kansas, pelting the Italian relentlessly, trying always to reach the jaw with a crushing right and pounding the body unmercifully when the men came to close quarters. But Kansas stood up under the battering, fighting back in spurts and at the finish had his hand raised in victory. He left the ring being mauled and pulled by frantic admirers who hopped between the ring ropes immediately when the decision was announced in Kansas's favor.

Let's get a few good photos of Rocky Kansas in here. This is a photo of Rocky (left) and Sammy Mandell facing off right before their fight in 1926, Rocky is pictured here demonstrating his punch to solar plexus of Mandell. Like I said before, Rocky Kansas was known for his wicked body punching.

This is a 1936 LA Salle Hats card of Rocky Kansas. This rare set was issued in 1936 by the La Salle Hat Company. Based in Philadelphia, that company distributed these cards featuring eight lightweight boxers. The cards themselves are basic. The fronts feature black and white pictures of the boxers along with their name and title reign at the bottom. The set was look back of sorts, as it included cards of past lightweight champions through history. It also included a card of Lou Ambers, then the world lightweight champion. Backs of the cards are blank. An envelope was used for the cards with a short description on it. Printed on the outside, the company called this, ‘A picture collection of famous lightweight champs furnished with the compliments of La Salle Hat Company, Philadelphia.’ The exact mode of distribution for these cards, however, is unknown. It is not clear if they were simply given to anyone or if a purchase was required. One interesting note here is that the cards do not appear to have been limited to only the Philadelphia area. We know that from the envelopes which, in addition to stating the cards are with the compliments of the hat company, also add, ‘and _____________.’ The blank line represents a blank box printed on the envelopes and specific stores used that area to either stamp or print their own name. Those stores were likely distributors and the envelope was used much in the way that late 1800s trade cards were used – cards with stock images that used by a variety of businesses. As this auction indicates with an envelope stamped by an Ohio business, the cards were likely distributed outside of Philadelphia. While I have listed this set in the Miscellaneous (U-Card) section, it could also be considered a trade card issue. These cards are not easy to come by. Finding one is an achievement and finding a complete set is extremely difficult.

Luis Villanova, aka Kid Azteca, legendary Mexican welterweight that fought from 1929 to 1961, his career spanned an unbelievable five decades. He was a thunderous puncher, Kid Azteca had one of the greatest left hooks in boxing history and he iced 114 opponents in his career, he's ranked number 6 for most knockouts all-time in boxing history.

Kid Azteca is one of Mexico’s legendary fighters. Azteca never won a world championship, but he was a top contender for the World welterweight title throughout most of the 1930s and 40s. He was one of Mexico’s earliest boxing stars, paving the way for the many great Mexican world champions who would take over many of the sport's lighter weight divisions from the 1950s onwards.

Born Luis Villanueva Paramo in Tepito, Distrito Federal, Mexico, Azteca’s birth date is generally given as being June 21, 1913, but some sources have placed his birth date as June 21, 1917, which would make him only 12 years old when he started his professional boxing career in 1929. Starting his career fighting under the name of ‘Kid Chino’, Azteca was a strong and fearless fighter, with a dynamite punch, that would score 114 knockouts during his career. Some of the top names that Azteca fought, included fighters such as Battling Shaw, Tommy White, Eddie Cerda, Joe Glick, Eddie Frisco, Ceferino Garcia, Manuel Villa 1, Richie Mack, Young Peter Jackson, Baby Joe Gans, Cocoa Kid, Chief Parris, Fritzie Zivic, California Jackie Wilson, Charley Salas, and Sammy Angott.

Azteca won the Mexican Welterweight title on October 23, 1932, when he out-pointed David Velasco over 12 rounds. It was the beginning of a tremendous 16-year reign, which would see him defend the title successfully 11 times, before vacating it, undefeated champion, on March 1949. Azteca would try and regain his title 10 months later, on January 28, 1951, but was stopped in 10 rounds by El Conscripto. By this time, Azteca was in his late 30s and fading, yet he carried on fighting until 1961, going 28-2-2 in his last 32 contests, although against lesser opposition than he had fought in his prime.

Kid Azteca finally ended his career with a 1st round knockout of Alfonso Malacara, on February 3, 1961. Azteca ended his career having achieved the rare feat of fighting within 5 decades, and scoring 114 knockouts, making him one of boxing’s most formidable punchers. Azteca’s final record was 192-46-11 (114 KO). Kid Azteca died on March 16, 2002.

Azteca is a legend, hard punchers are fascinating. I'm always searching ebay, looking for Kid Azteca items, cards, photos, but unfortunately he just doesn't have much to collect at all.

It's hard to believe Kid Azteca fought in five different decades, the 1920's all the way through to the 1960s, that is insane. This photo was taken as he started to get older.

Iconic photo right here. There's different kinds of shell shock, there's the shell shock of being in a real war, which nothing can compare to. But there's also the shell shock of being in physical combat with another person inside of a ring, taking physical beatings. This is one of my favorite boxing photos ever taken, Carmen Basilio aka "The Onion Farmer" being held back by the referee after stopping Tony DeMarco aka "The Boston Bomber" in round 12 of their November 1955 rematch in Boston for the world welterweight title. Basilio and DeMarco put eachother through pure hell, and this image captures the shell shock on Basilio's face at the conclusion of two brutal wars with DeMarco. Tony DeMarco was a hard hitting, relentless man, they didn't call him "The Boston Bomber" for nothing. They took years off of each other's careers and their rivalry is one of the most epic in boxing history. In the rematch, Basilio retained the world welterweight title he won from DeMarco in their first fight which ended in almost identical fashion when Basilio TKO'D DeMarco at 1:52 in round 12. At the conclusion of their rivalry, Basilio said of DeMarco, "When he hits you, you know you've been hit. All you have to do is ignore the effects. If you think it's going to hurt, then it will." Carmen Basilio was a hard man. Make no mistake about that.

I actually own one of the two known type 1 photos to exist of the above image. I love this iconic image, the expression on Carmen Basilio's face really captures what it's like to go through the physical punishment of boxing.

Virgil Akins was a hard luck fighter who fought as a professional for about 15 years and briefly held the welterweight championship. Fighting during the post-World War II era, Akins, aka "Honey Bear," was clearly a good fighter that scrapped his way to a world title.

Unfortunately, despite a good amateur career, Akins lost five of his first 20 pro fights at lightweight, one by stoppage. While it was a tough era in the division, his inconsistency pushed him more toward the category of journeyman. Akins still managed to get wins over future champions Wallace "Bud" Smith and Joe "Old Bones" Brown, but the wins didn't carry the same weight at the time.

Akins moved up in weight in the 1950s, however, and defeated contenders like Isaac Logart, Joe Miceli and Henry Hank, and former champion Tony DeMarco. The meaningful wins were apparently too few and far between, even for those close to him.

"A dark cloud has been hanging over me since the night I won [the welterweight title in 1958]," Akins later said. "Nobody expected me to beat Vince Martinez, including all my friends. They even bet on Martinez and when I saw them they'd say, 'Hey, I lost a lot of money because of you.' Even my cousin bet against me. He was mad at me for years and every time he'd see me he'd say, 'You owe me money.'"

Akins destroyed Vince Martinez with a 4th round stoppage to win the welterweight title in 1958, and lost the title by decision to Don Jordan the same year. The decision was fair, but both Jordan and Akins had direct ties to the mob figures deeply involved in boxing who would later serve time for their corrupt dealings.

In 1962, Akins suffered a badly detached retina against a fighter named Rip Randall, and the injury ended his career.

After boxing, Akins was a custodian and a construction worker. He cooked at a hotel for a time, worked in a supermarket and even was a shipping clerk at a candy company. At the candy place, Akins re-injured his left eye and lost vision completely.

Akins went on to separate from his wife and lose his career earnings from bad investments and tax issues. In 1969, a benefit fight card was held in his honor. Few showed up and Akins walked away with $200.

In the 1970s, Akins was walking home with a $100 paycheck when he was jumped by thieves who cracked him over the head with a tire iron and took his check.

"I saw the colored lights when I got hit," he said. "But I remember thinking, 'I still haven't been knocked out.'"

From his early days in St. Louis, fighting it out as a youngster, to his older days struggling through life, Akins caught few breaks.

"Some get the breaks and some don't. Being world champion was the biggest break I ever got, but it didn't lead nowhere."

Virgil Akins is fun to watch on film, win or lose he always came to fight. He was given the nickname "Honey Bear" because he could be vicious like a bear, but smooth like honey. He started off his career with the style of a pure boxer, leading to mixed results, but when he hooked up with a pharmacist/part-time fight manager named Eddie Yawitz in St. Louis, he became a really dangerous fighter. Akins always had brutal knockout power, Yawitz channeled that power, and boy, the voltage got turned up right quick. This is one of my favorite Ring magazine covers, it says "Murderous Fists! The Story of Virgil Akins' Rise To The Championship."

IBRO

Virgil Akins: His Long Journey to the World Welterweight Title

By: Dan Cuoco

Virgil Akins was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on March 10, 1928. The Akins family lived in a three-room flat at Second and Mullanphy Streets, a short distance from the Mississippi River. His father died when he was nine years old, and the family, which included three sisters and a brother, were poverty-stricken. Young Virgil chopped railroad ties, which he sold as kindling wood, and took other odd jobs to help his family. After he married and had two children, ten people were living in those three rooms.

Before turning pro, he held the St. Louis District lightweight crown in 1946 and 1947 and, later in the year, was a member of the Western Golden Gloves team. His amateur record was a respectable 72-7. Two prominent opponents he defeated as an amateur were Del Flanagan and Jesse Turner.

Pre-Prime (November 1947- December 1954)

Virgil turned pro in Kansas City on November 4, 1947, under the management of Johnny Tocco. He fought as Jimmy Foxx for his first two pro fights and changed back to his birth name on his return to St. Louis on March 10, 1948, under the management of Arthur Liebert and trainer Turuche (Chico) Larretz. Lou Wallace took over his management from 1948-1952, and George Gainford managed him in 1953.

His pro career started well, winning ten of his first eleven fights, three by kayo. His only loss occurred in his fourth pro fight on April 5, 1948. Virgil was initially announced the winner on a foul in a bristling battle with Charley Baxter of Cincinnati, but ten minutes later, the boxing commission reversed the verdict. Virgil went down in the third round of the scheduled six-round preliminary at Kiel Auditorium in St. Louis from a left hook that appeared low. When he was unable to continue and seemed semi-paralyzed for several moments, referee Paul Spic recommended the fight go to Virgil on a below-the-belt foul. However, he was overruled by Dr. Freedman, who said evidence showed he was not fouled. The commission then awarded Baxter a technical knockout.

In a rematch, sixteen days later, Virgil won a unanimous decision over Baxter in an action-packed six-rounder at Kiel Auditorium in St. Louis. But, unfortunately, his record became spotty after his ten-and-one start, looking good one night and bad another night. For every Bud Smith, Joe Brown, Freddie Dawson, Luther Rawlings, and Tommy Campbell he beat, there were losses to less talented fighters, such as Joe Fisher, Nelson Levering, and Gene Parker.

In 1951 he twice defeated Wallace “Bud” Smith, Tommy Campbell, Freddie Dawson, and Luther Rawlings. After losing two decisions to Joe Brown, Virgil won a decision over Brown in their third meeting. Virgil’s ten-round split decision win over long-standing number one ranked lightweight contender Freddie Dawson on September 26, 1951, moved him into Ring magazine’s December 1951 world lightweight ratings for the first time at number four. Dawson’s subsequent departure to the welterweight division elevated Virgil to number three in Ring magazine’s January 1952 issue. Further victories over Luther Rawlings and Joe Brown elevated Virgil to number two in Ring magazine’s ratings.

Miceli vs Akins

In 1952, Virgil retained his number two Ring rating with four consecutive kayos over Baby Leroy (TKO 4), Joe Gilmer (TKO 9), Henry Davis (TKO 9), and Jay Watkins (KO 2) until back-to-back losses to welterweights Johnny Saxton and Joe Miceli broke his streak. Saxton rallied from a first-round knockdown to win a unanimous decision. Against Miceli, Virgil fought a defensive, retreating bout as he appeared weary of Miceli’s left hook. The referee warned Virgil to pick up the pace after four rounds, but he was hurt in the fifth and returned to his cautionary tactics. These two losses saw him tumble in the Ring ratings to number eight. After the Miceli fight, Virgil stayed out of the ring for seven months and was dropped from the Ring ratings.

In 1953 his career dropped to an all-time low as he saw his losing streak reach four, losing a majority ten-round decision to Johnny Gonsalves and a devastating tenth-round stoppage loss to Hawaiian welterweight Phil Kim.

Phil Kim vs Virgil Akins

The Kim fight occurred on August 29, 1953, in a nationally televised main event at Rainbo Arena, Chicago, Illinois. Virgil, who was leading on two of the three official score cards through the first nine rounds, was knocked down twice in the final round, both from left hooks to the head. He went down for a four-count the first time and then for nine, after which referee Joey White stopped the bout at 2:11 when he was unable to raise his arms. Both fighters weighed 141 ½ pounds. Dr. Irving Slott, the athletic commission physician at the ringside, administered oxygen to him and later ordered his manager George Gainford to take him to Columbus Memorial hospital as a cautionary measure. Dr. Slott said there did not appear to be anything wrong with him except for exhaustion. After Virgil’s loss to Kim, he returned to St. Louis but was idle for ten months because he found it tough to get a fight. During that time, he left the management of George Gainford and hooked up with Bobby Gleason.

On June 2, 1954, Virgil returned to the ring after a 10-month layoff to face journeyman Joey Greenwood of Akron, Ohio, in a ten-round semi-final at St Louis Arena. Virgil, rusty after the long layoff, still had enough to pound out an eight-round TKO over Greenwood. Virgil scored a knockdown in the fifth and two more in the seventh. Greenwood wasn’t able to come out for the eighth. He was idle for another four months when he traveled to New Orleans on October 16, 1954, and lost a ten-round split decision to local fighter Andrew Brown at the Coliseum. Brown piled up a commanding lead in the early rounds, only to have Virgil come on strong in the last three stanzas. Ten days later, Virgil won a unanimous eight-round decision over Henry Hank of Detroit in the featured bout at Motor City Arena. Virgil floored Hank twice – once in the first round and again in the third. Hank made his best showing in the second round when he started a counterattack. After that, Virgil was never in difficulty and appeared to be using the final rounds of the fight as a workout. After only engaging in five fights in the past two years and no prospects in sight, Virgil, now a free agent, was ready to call it quits.

Prime (March 1955 – June 1958)

In early 1955 Virgil returned to St. Louis discouraged and ready to give up boxing. Training meant nothing to him, as he was merely going through the motions. Then, one day in the gym Eddie Yawitz, a St. Louis druggist who managed fighters as a sideline, noticed the change in Virgil’s demeanor and struck up a conversation with him. He told him that anyone who could punch like him should be a champion. Akins looked at Yawitz at first through cynical eyes. At age 27, he felt that the series of managers since he turned pro had fleeced him. But as the druggist kept repeating his words of encouragement, Virgil’s morale began to lift. Finally, Virgil blurted out, “I’d like to fight for you.” The druggist quickly backed up his enthusiasm with cash. Yawitz joined forces with Bernard Glickman, a Chicago manufacturer with good boxing connections who came on as co-manager. Before signing with Yawitz and Glickman, Akins’ record stood at 27-13-0 (KO 11/KO by 2), with five losses occurring in his last seven fights.

Conscious of Virgil’s natural punching power, they let him do what he had always wanted to, and it came naturally. He became a puncher rather than a boxer. Virgil was willing to give up some of his defense to probe opponent weaknesses and the willingness to take punches to land his own power punches. The results were immediate. During his three-year run to the world title he compiled a record of 23-4-2, 18 by knockout.

Akins vs Delaney

Virgil’s breakout year turned out to be 1955. Returning to the ring after a five-month layoff, Virgil stopped Johnny Brown in the tenth-round at Miami Stadium in Miami; stopped Tommy Maddox in four-rounds at Marigold Gardens in Chicago; drew with Johnny Brown in a rematch at the Arena in St. Louis; scored an upset eight-round knockout over middleweight contender Ronnie Delaney at St. Nicholas Arena in New York; stopped former conqueror Joe Miceli in the first-round at St. Nicholas Arena in New York; stopped Bill Sudduth in eight rounds at Marigold Gardens, in Chicago; won a ten-round split decision over welterweight contender Issac Logart at St. Nicholas Arena in New York; won a unanimous decision over Harold Jones at Victory Field in Indianapolis, Indiana; and ended the year losing a ten-round decision to Issac Logart in their rematch at Madison Square Garden in New York. Virgil’s upset of middleweight contender Ronnie Delaney of Akron, Ohio, moved him into Ring magazine’s world welterweight ratings at number six. Subsequent victories over Miceli, Sudduth, Logart, and Jones elevated him in the Ring ratings to three, but his loss to Logart dropped him to number six by year’s end.

Virgil’s stunning kayo of Delaney was one of the year’s biggest surprises. The 25-year-old Delaney entered the ring with a record of 59-1-3 (KO 27), and his only defeat had occurred seven years previously, in 1948. The Akron southpaw had been touted as one of the most dreaded fighters in the ring and was a top-heavy favorite over Virgil. At no time during the bout did the odds seem justified. Going into the eighth round, the fight was dead even. Neither fighter had been in trouble at any time during the bout, and the sudden ending was totally unexpected. As Delaney backed away from a clinch, Virgil lashed out with a left hook. It caught Ronnie flush on the chin, and he staggered. Virgil promptly stepped in with a right cross, and Delaney went down flat on his back. At eight, he tried to rise but pitched over on his face as referee Barney Felix counted him out.

Akins vs Constance

In 1956, Virgil entered the ring eight times, winning six by kayo, one by decision, and losing one by decision. He stopped Rudolph Bent in five rounds at Valley Arena in Holyoke, Massachusetts; kayoed Clarence Cook in four rounds at the Sportatorim in Dallas, Texas; stopped Mel Barker in eight rounds at the Alnard Temple, in East St. Louis, Illinois; stopped Andy Watkins in two rounds at Alnard Temple, in East St. Louis, Illinois; won a unanimous decision over Hector Constance at the Arena, in St. Louis, Missouri; stopped Don Jose at Kallio’s Arena in Monroe, Louisiana; lost a unanimous decision to Charley Sawyer, at Legion Stadium in Hollywood, California; and kayoed Pat Lowry at Biscayne Arena, Miami Florida. He ended his successful 1956 campaign as Ring magazine’s fifth-ranked world welterweight contender.

Virgil started 1957 with five consecutive victories before dropping two out of his last four fights. He won a ten-round unanimous decision over Sammy Walker at Memorial Auditorium in Buffalo, New York; stopped Al Andrews in six rounds at Kiel Auditorium in St. Louis, Missouri; won a unanimous ten-round decision over Franz Szuzina at Kiel Auditorium in St. Louis, Missouri; stopped Jimmy Beecham in three rounds at Capital Arena in Washington DC; won a ten-round unanimous decision over Walter Byars at the Arena in Norfolk, Virginia; lost a ten-round unanimous decision to Franz Szuzina in a rematch at Kiel Auditorium in St. Louis, Missouri; stopped Garnet (Sugar) Hart in eight rounds at Public Hall in Cleveland, Ohio, lost a ten-round decision to Gil Turner at Convention Hall in Atlantic City, New Jersey; and kayoed Tony DeMarco in Boston, Massachusetts, in fourteen rounds billed in Massachusetts as a welterweight title match. His impressive knockout of top-ranking Tony DeMarco elevated him to the top of the division by Ring magazine and the NBA and in prime position along with Issac Logart, Gil Turner, Vince Martinez, Gaspar Ortega, and George Barnes to compete in the welterweight elimination tournament to crown a successor to Carmen Basilio, who vacated the title when he beat Sugar Ray Robinson for the middleweight title.

Akins Rises to the Occasion

Dan Daniel of Ring magazine wrote, “Akins has proved himself eminently able to rise to an occasion. He came into the competition as an underdog. Gil Turner had beaten him. This after Virgil’s eight-round knockout of Sugar Hart and on top of a defeat by Franz Szuzina. Once entered in the welter eliminations, Akins stopped fooling around. He made Tony DeMarco retire from the ring with two knockouts in Boston.”

Akins vs DeMarco January 21, 1958

The first Akins-DeMarco fight took place on October 29, 1957, and was among the most savage and exciting fights ever held in the Boston Garden. In a war of attrition, Virgil floored DeMarco three times in the 14th round for a knockout. Virgil spent the early rounds sending out left jabs and hooks to score against the hard-hitting DeMarco and picking off Tony’s blows with a slip of the shoulder and dart of the glove. Virgil was dropped in the 12th round before finishing DeMarco with a smashing two-handed flurry at 1:17 of the 14th – the 6th time in the bout DeMarco had been on the canvas. After the fight, the NBA and the NSAC said that they did not regard the meeting as a championship bout but only as an elimination in the tournament, which would ultimately name a successor to Carmen Basilio.

Akins and DeMarco met in a rematch on January 21, 1958, again at the Boston Garden, once more for the Massachusetts version of the welterweight championship. Virgil scored a twelfth-round technical knockout in another brutal match. He finished the bout with a jarring right uppercut forcing referee Eddie Bradley to stop the fight. DeMarco had been down once in the eighth round and twice in the eleventh but didn’t know how to quit until Bradley made the decision for him before an overflow crowd of some 15,000 screaming fans.

With top-rated DeMarco out of the way, the final six vying for the vacant title were Virgil Akins, Isaac Logart, Vince Martinez, Gil Turner, Gaspar Ortega, and George Barnes. Isaac Logart advanced when he defeated Gasper Ortega in twelve rounds on December 6, 1957. Six days earlier, Vince Martinez also advanced with a twelve-round majority decision over Gil Turner. With three fighters left in the tournament due to George Barnes’ withdrawal, Julius Helfand, chairman of the state commission, and the championship committee arranged a draw to determine the next pairing. Nat Fleischer, publisher of The Ring, drew out the names, first Akins and then Logart, so Martinez automatically got the bye.

Akins vs Isaac Logart

On March 21, 1958, Virgil stopped the shifty Issac Logart in the sixth round of their welterweight tournament semi-final at Madison Square Garden. The end came with surprising suddenness. Logart had dazzled Virgil with his flashing hand speed and clever maneuvering. In the first, second, fourth, and fifth rounds, Logart landed significantly more punches than Virgil. Until the sixth, Virgil’s best round was the third, when he came on strong in the last two minutes. He scored with some right hands for the first five rounds, but none landed flush. Virgil finally caught up with Logart early in the sixth round and staggered him with two right hands to the jaw, followed by a right to the body and a push that dropped him. Logart arose groggily at three and was given the mandatory eight count. Virgil belted away at Logart with both hands. A right sent Logart sagging into a sitting position on the ropes. Although he didn’t hit the floor, referee Harry Kessler ruled it a knockdown and gave him another eight count. Virgil roared in for the knockout. He smashed Ike to the ropes with both hands. With a cut over his right eye and a bloody mouth, he was headed to the canvas when Kessler stopped the fight. This was their rubber match. They had met twice before in 1955. Virgil won the first by split decision, and Logan evened the score, winning a unanimous decision in the return bout.

Virgil hardly got a chance to enjoy his victory. Right after the bout, the New York District attorney subpoenaed both fighters and their managers as part of a continuing investigation into the influence of underworld figures on boxing in New York. Despite the odds favoring Logart, a lot of “smart money” had been placed on Virgil just before fight time. In the end, a Grand Jury cleared all parties of any wrongdoing.

On June 6, 1958, Virgil met Vince Martinez in Virgil’s hometown of St Louis, MO, for the vacant world welterweight championship. Virgil, moving fast out of his corner, didn’t waste any time. Just thirty seconds into the opening bell, the entire pattern of the fight was set. Virgil moved in and landed a left to the side of Vince’s head, a solid left hook to the body, followed by a right crossing over Martinez’s left. Down went Vince. Caught cold, Vince never was in the fight after the first knockdown. Before the round had ended, he had been down four more times.

Akins kayoes Martinez in fourth round

The second round saw Martinez remain off the canvas for only three minutes of the fight. Although he was completely on the defensive with a cut under his right eye and nose bleeding profusely, he appeared to be gaining strength. He made good use of his left jabs with one flurry of combinations more like the Martinez the fans had expected to see

But Vince’s short rally didn’t last long. Twice more in the third and twice more in the fourth session, Martinez was slugged to the canvas by Virgil’s booming right before the referee raised his hand in triumph at 52 seconds of that fateful fourth with Martinez on the deck, drained of all ability to fight. Kessler explained later that he could have counted to thirty over Martinez without him getting up.

The casual onlooker must have found it difficult to understand how a cautious, clever, experienced boxer like Vince Martinez could have been demolished in such a hurry by his hard-hitting but slower-moving opponent. Virgil explained after the fight that he had exploited a weakness he spotted in Martinez’s style in watching four of Martinez’s televised fights. Martinez telegraphed his vaunted left hook. He made a peculiar movement of his head and dropped his left hand too low before striking with it.

Philadelphia Boxing Historian Chuck Hasson shared his observations with me. “Of course, anybody can be caught cold – but I remember after Akins kayoed Isaac Logart in the welterweight tourney semi-final, he was asked his thoughts on the upcoming Martinez match, and Virgil said he would kayo Vince because Vince had a habit of double jabbing, dropping his hands and leaning back, real pretty like, and when Vince does that he has to throw two straight right hands the first probably missing but the second will be on the money. Obviously, Vince wasn’t listening because 30 seconds after the fight started, the scenario played out just as the prognosticator Akins had called it. I think Akins was one of the most dangerous welters in history from 1955 to 1958 (check his record).”

After winning the title, Virgil took his wife to Mexico. When he returned, he discussed prospective challengers with Eddie Yawitz. They both hoped that recently dethroned middleweight champion Carmen Basilio would reenter the welterweight division because he would give them their biggest payday. Moreover, they didn’t fear Carmen because they were sure Virgil hit harder than anyone in the division. This confidence made Virgil announce that if Basilio wasn’t available, he didn’t care who he fought.

Father Time Catches Up to Athletes

Father time catches up to athletes, sometimes gradually and sometimes overnight. But it is most common in professional fighters because of the punishment they endure throughout their careers. At age 30 and having engaged in over 70 fights, Virgil’s body’s physicality eventually caught up with him, and naturally so, starting with his fight against Charley (Tombstone) Smith. When he tried to counter, he found his punches were falling short and missing his target repeatedly. Moreover, his face and eyes were also paying a heavy price.

Post-Prime (August 1958 – March 1962)

Akins stops Smith in final round

On August 20, 1958, at Chicago Stadium, Virgil looked nothing like a champion against Charley (Tombstone) Smith and was a beaten fighter for nine rounds. Smith outboxed him and badly cut his left eye and bruised his right eye. Virgil was unable to land solidly on his taller opponent and was equally unable to keep Smith’s jolting left jabs from connecting. Going into the final round, he was behind on the scorecards of all three officials. Virgil came out for the tenth with a rush and swarmed all over Smith. Then, out of nowhere, he landed a crushing left hand on Smith’s face, and down he went. Smith staggered to his feet at the count of eight in obvious distress. Virgil quickly maneuvered him into a neutral corner and had him all but out on his feet when referee Frank Sikora stopped the fight at 1:18 of the final round.

On September 18, 1958, Del Flanagan won a decisive ten-round decision over Virgil at the Saint Paul Auditorium in Minnesota, utilizing his speed and neat combination punching. Virgil, apparently protecting bruises above his eyes inflicted in the Smith fight 29 days earlier, fought in spurts winning only the sixth and ninth rounds. Virgil blasted Flanagan from pillar to post in the ninth round, winning the round decisively. But Flanagan won the tenth round just as decisively, as he finished much stronger. When the fight was over, one again asked why did Virgil take the fight. It must have been for the money because even if he won, he didn’t figure to gain anything from it. To make matters worse, his one-sided beating eventually cost him his long-sought lucrative fight with Carmen Basilio.

On October 22, 1958, Don Jordan won a twelve-round split decision over top-rated Gaspar Ortega in a twelve-round elimination bout and earned a world title fight with Virgil. After viewing the fight on television, Virgil boasted confidently that he would knock out Jordan within three rounds. “There isn’t a welterweight around who can stay with me,” he said. “I’m the champion because I’m the best. I’m no second Kid Gavilan or Ray Robinson. I’m the first Virgil Akins.”

Jordan vs Akins December 5, 1958

On December 5, 1958, Virgil lost his world welterweight title in a stunning upset to 3-1 underdog Don Jordan at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles. The fifteen-round decision was unanimous by a substantial margin. Jordan maintained a torrid pace throughout the bout, whipping in a string of left jabs, left hooks, and occasional rights to the head when in close. Seldom did he allow Virgil punching room, but when he did, he often got the better of the exchanges. Jordan hurt Virgil in the tenth and eleventh rounds. By the end of the eleventh, Virgil’s face was smeared with blood. His left eye was cut and beginning to swell. Virgil picked up the pace in the latter stages and threw punches desperately in an effort to score a knockout but was never able to catch the smooth boxing and active Jordan. Referee Lee Grossman scored 145-138; Judge Mushy Callahan scored 145-132; and Judge Tommy Hart 146-136.

Virgil was so sure he would knockout Jordan within a few rounds that he had booked a 9:15 PM airplane reservation to Los Angeles international airport. He allowed himself two hours and fifteen minutes from the start of the fight to get it over with and make the fifteen-mile trip. After fifteen rounds, he had to take a later plane. Being overconfident and not mentally or physically prepared can lead to what Mike Margolies, a sports psychology consultant, describes as an athlete ‘sleepwalking through a game.’ Oh, how prophetic!

His title loss and a subsequent rematch with Jordan destroyed his confidence

His title loss and a subsequent rematch with Jordan destroyed his confidence resulting in his career spiraling downhill until his retirement in March 1962. During that time span, he fought 23 times, compiling a record of 10-12-1 (KO 5/KO by 0).

In 1959 he lost a unanimous decision to Don Jordan in a world title rematch; lost a unanimous decision to Luis Rodriguez; won a majority decision over Stan Harrington; lost a majority decision to Kenny Lane; and lost a split decision to Denny Moyer.

In 1960 he lost a unanimous decision to Don Fullmer; lost on points to Wally Swift; won on points over Fernando Barreto; won a unanimous decision over Charley Scott; lost a unanimous decision in a rematch with Luis Rodriguez; knocked out Carl Hubbard in five; and lost a split decision to Candy McFarland.

Akins vs TJ Jones

In 1961, he stopped TJ Jones in nine; won a majority decision over Gerald Gray, won a unanimous decision over Billy Collins, stopped Cecil Shorts in eight; lost a majority decision to Henry White; lost a unanimous decision in a rematch with Kenny Lane; stopped Jose Antonio Burgos in one; fought a draw with Stefan Redl; stopped Vince Bonomo in four; and lost a unanimous decision to Ralph Dupas.

On March 20, 1962, Virgil engaged in his last professional fight losing a unanimous decision to Rip Randall in Houston, Texas. He was forced to retire when it was discovered he was suffering from a detached retina in his left eye. His final ring record: 62-31-2 (KO 35/KO by 2).

But like thousands of fighters before and after him, life after boxing doesn’t always end with a happy story. His restaurant (The Honey Bear) was forced to close, and he went from one job to another. He was a construction worker, a cook at a local hotel, a shipping clerk at a candy company, and a high school custodian. An accident at the candy company reinjured his retina and cost him the vision in his left eye. His personal life also suffered as he and his wife of 23 years separated. In addition, his earnings from boxing, estimated at more than $150,000, were lost because of income tax problems, bad investments, and bad advice from men he used to trust.

In 2005, Virgil was honored with a place on the St. Louis Gateway Classic Walk of Fame, which pays special tribute to African-American men and women from St. Louis who have made significant contributions on the local and national level.

Virgil Akins died in St. Louis on January 22, 2011 at the age of 82.

This is Virgil Akins' vs Isaac Logart, Logart was a tough Cuban fighter, he and Akins fought a grueling trilogy with Logart winning the first two and Akins stopping Logart in the third fight.

Virgil Akins and Tony DeMarco fought two savage wars, both ending with DeMarco being TKO'd. The DeMarco fights really showcased how good Akins' chin was, when DeMarco hit people flush, they usually went to bed. Akins withstood multiple power combos against DeMarco and came back in a thunderous fashion. DeMarco was one of the most exciting and electrifying fighters in the sport's history and he was in some real knock down drag outs in his career, after his two fights with Akins the damage really piled up on DeMarco and he wasn't the same. This is a write-up on the second bout.

Virgil "Honey Bear" Akins nearly ended the career of Tony DeMarco when he defended the Massachusetts version of the welterweight title with a 12th round TKO at Boston Garden in Boston, Massachusetts on January 20th in 1958.

In this rematch of an exciting first bout that saw both fighters beaten up and knocked down before a wild late-rounds knockout, they once again delivered on excitement, though Akins came on late to pummel the former world champion.

One ringside report read:

"Off to a brilliant start, the gritty little, heavy-bearded DeMarco was leading by a country mile for seven rounds. The North End Italian had piled up his lead on clever boxing and throwing punches to the midriff. But then Akins came out of his shell, where he had been hiding, waiting for openings. Virgil scored the first of three knockdowns in a blazing eighth round, dumped his man twice more in the 11th and while DeMarco was stumbling around in the ring in the 12th under a heavy barrage—finished the fight with a grave-digging right uppercut to the stomach and right to the head."

Akins was reported as having "slipped to the canvas" after being hit by a hook in the 4th round, but he cut DeMarco over the eye and laid leather on him badly enough that DeMarco pledged to retire while back in his dressing room. He fought six more times over the next four years, but clearly lost portions of himself for being an exciting fighter.

"Honey Bear" Akins would confirm his claim to the welterweight championship later in 1958, but he would also go on to have severe eye issues that affected his career.

Virgil Akins vs Vince Martinez. If you're not familiar with Vince Martinez, he was one tough and clever SOB with an iron chin, going into this fight with Akins, Martinez had a record of 60-5, and had never been knocked down in a fight. This was a one-sided affair, with Akins on the attack from the opening bell, sending Martinez to the canvas seven times before the slaughter was finally stopped and the referee intervened in round four to declare Akins the new world welterweight champion by a TKO.

Don Jordan defeated Virgil Akins in their first match for the world welterweight title on April 24, 1959, by unanimous decision in 15 rounds. Jordan won the fight by outboxing the hard-hitting champion Akins with a strong left jab and right hand, despite Akins's aggressiveness. This victory upset the 7,344 attendees at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles and made Jordan the new world welterweight champion. The fight got very rough, with both fighters spilling through the ropes.

There's one more Virgil Akins fight I want to mention, his fight with Henry Hank. The fight took place in 1954 in Detroit and Hank was 26 years old at the time, Hank would later become one of the most dangerous fighters in boxing history, and much like Akins, Hank could be explosive and carry serious power. In 1962, Hank waged all-out war with Dick Tiger in one of the greatest fights I've ever seen, it was basically "bombs away" for 10 rounds with Tiger emerging victorious, both fighters unloaded some brutal leather on each other, it was the kind of fight that can leave a man scarred for life. Anyway, in 1954, Virgil Akins took on a green Henry Hank and Virgil Akins defeated Henry Hank. Akins won the 8-round bout by unanimous decision. During the fight, Akins knocked Hank down twice, once in the first round and again in the third. Unfortunately there's no photos available of that fight, but here's a photo of Henry Hank.

Good shot of Akins, this is a promo photo, these types of photos were given out to the press by the trainers and managers of fighters to promote their fighter. If you'll notice it has Eddie Yawitz's name and contact info on it. These promo photos with the trainers contact info can be extremely rare and hard to find.

Israel Vazquez vs Rafael Marquez, 2010. These two put on four legendary fights that no fan could say didn’t entertain, each fight had the blood, sweat and tears you would expect when two bantamweights put it all on the line. The fourth fight was undoubtedly one too far for Vazquez, who it was rumoured wore a face-mask in camp due to fears his numerous cuts over the years would open up. As expected that is exactly what happened in Part IV against fellow Mexican Marquez. Vazquez’s left eyebrow looked like it wanted to escape at the end and he had a big slit above the right eye as well.

In 2018, Zolani Tete knocked out Siboniso Gonya in just 11 seconds in the quickest-ever ending in a world title fight.

The 29-year-old Tete landed a brutal right hook just six seconds into the bout to retain his WBO bantamweight title at Belfast's SSE Arena.

And the ref officially waved away the contest just five seconds later as the South African lay sprawled on his back.

Thankfully, the challenger Gonya made it back to his feet with the help of an oxygen mask, but came up well short in his first world title fight, suffering his second loss in his 13th outing.

The previous record for fastest ending in a world title fight belonged to former WBO super-bantamweight champion Daniel Jimenez, who swiftly dealt with Harald Geier in 17 seconds back in 1994.

“I want to be remembered as the man who changed the pay scale for featherweights, who put the sparkle back in boxing after Muhammad Ali left, the man who took risks with his ring entrance, the man who, before the fight, would do a front flip into the ring without even thinking about turning an ankle, and then knocking his man out. I mean out.”

— Prince Naseem Hamed

Prince Naseem wasn’t just a boxer; he was a showman who changed how people saw the sport.

One of the best chins in the original weight divisions and we come to featherweight Nel Tarleton, who had a 19-year career in which he fought 147 times and was never knocked down, stopped or knocked out, Nel was a fairly light puncher so most of his fights went the distance with the majority of those going 10 rounds or more. Tarleton also had a potentially big disadvantage with stamina as he only had one lung but his stamina and chin were both at the very top level as he fought 1617 rounds and was never off his feet. If you have the heart you may be able to do some amazing things. Born in 1906, Nelson Tarleton was slinder of build and from age of two he had only one lung. He went on to become a successful British boxer winning the Lonsdale Belt twice and twice fighting for the National Boxing Association Championship losing both fights to American fighter Freddie Miller. His professional record was 118 wins, 8 draws, and 21 losses in 147 fights. He was the British Featherweight Champion three times and was the first boxer to twice win the coveted Lonsdale Belt. Lacking natural physical power, his boxing skills and speed were such that he scored 43 knockouts in his 118 wins. Missing a lung but with the heart of a lion, Nel Tarleton over came his physical limitations to become a 3 times British Champion.

Never judge a book by its cover...

'The doctor looked amazed when I stepped on the scales and failed to move them. He looked at me pityingly and said: 'No, my son, you are too weak and frail. I can't pass you.' I pleaded with him to allow me to enter the ring, and he put me through all sorts of exercises to see if I had any strength. He brought his stethoscope to my chest and went over me as if I were going a medical examination.

Eventually, to my joy, he agreed to let me fight, though I knew at the time he was doubting whether he acted wisely. Anyway, I got into the ring against a certain Sergeant Telford, I wondered whether it had not been better to stay at home. Here was a well-developed bantamweight who, I could see, carried plenty of beef. I confess I felt nervous and am sure the the spectators sympathized with me. There and then I made up my mind the sergeant would not catch me, and he certainly did not.

I boxed him with my left hand, and being lighter was much quicker, so I could get in my punch and slip away again before he could counter. I made the sergeant chase me all around the ring. Every minute his temper got worse. He kept saying to me: 'Come here, you little devil, and have a fight,' but I kept on the move.

Then he said 'I'll knock you into the middle of next week when I get you,' but I just prodded out my left hand and was away again before he could do it. I knew that if once I got close it would be the end of me. However, he didn't catch me, and I won the contest on points. Still, I was glad to get out of the ring and away from the bloodthirsty sergeant.

The first man who spoke to me as I jumped out of the ring was the doctor who had examined me and he was the first to offer his congratulations. I do not think that doctor will ever judge by appearances again." - Nel Tarleton

I love photos that were used on trading cards, and this is the photo of Nel Tarleton that was used on his 1935 JA Pattreiouex Sporting Celebrities card. There are two different variations of this card, the normal size and the thinner version, the thinner version can be more difficult to find. This is the same set that features the iconic Joe Louis rookie card, the thinner version of the Louis rookie card can be quite pricey, regardless of the grade. Here are both versions of the Nel Tarleton card. I would love to own the type 1 original photo that was used for this card.

Michael Moorer stopped an undefeated Francois Botha while making his first defense of the IBF heavyweight title with a 12th round TKO at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, Nevada in 1996.

Though he was 35-0, Botha was lightly-regarded in the U.S. Moorer won the vacant IBF belt several months earlier, but he was in the midst of bouncing back from his knockout loss to George Foreman.

During the fight, Moorer had to be convinced to fight harder by his trainer Teddy Atlas a few times. Moorer slowed his pace in the middle rounds after a good start and Botha had a few good rounds himself. Atlas yelled at Moorer in the corner after the 7th, and on cue Moorer fought harder and turned the tide.

In round 11, Moorer put Botha down two times. Moorer then forced referee Mills Lane to step in with a sustained attack in the final round.

Terry Downes, "The Paddington Express" on boxing and writers:

"I also found out not to believe everything I read, because there are writers, I think, who know about writing but little about fighting. And since fighting became my business I spent a lot of time at it. That's what makes me give opinions that often differ from the writers. I'm not an obstinate guy and I hope I'm always willing to learn, but I can count the writers on one hand whose opinions really count with me.

If I'd listened to them all I'd have been retired years ago, without even winning a world title, and very likely skint. Tom Phillips, then with the Daily Herald, said I should retire before I went on to win the world crown, had three world-title fights, and I finished up with a fourth shot. How wrong can you get?

I just wish all writers would get out of this habit of writing-off a boxer because of one defeat. Did anyone write-off Dempsey or Louis when they were both knocked out long before they became world heavyweight champions?

I made up my mind pretty young that there were just as many mugs among newspapermen as there were among us fighters. Yet it was publicity and, to some extent, newspaper support that got me to the top. Fighters can't survive without it." - Terry Downes

Terry Downes actually had two nicknames, "The Paddington Express", and "Dashing, Bashing, Crashing", both nicknames were a reflection of his come forward, aggressive style. He was a good puncher – though not a one shot KO kind of fighter – he broke you with an accumulation of blows and the pace he set. His style made for a lot of very entertaining fights, he was a crowd pleaser. Downes could take a punch, he was never counted out in a fight, but his face — especially his nose, which he called his “perishin’ hooter” — suffered for it. He was a bleeder who needed plastic surgery to remove scar tissue and 364 stitches over all to close the many cuts to his face. Terry Downes was a good fighter, good enough to beat Paul Pender and become undisputed world middleweight champion, and also good enough to beat the great Joey Giardello and Sugar Ray Robinson, albeit a faded Robinson. But Terry was a class act and as honest as it gets, after his victory over Sugar Ray Robinson, Terry famously said, "I didn't beat Sugar Ray Robinson, I beat his ghost." Terry was also quick witted and humorous, after his loss to Dick Tiger in 1957, in which Downes was floored, cut and then stopped in six, a member of the press went to his locker room and asked him, "who do you want to fight next?' To which Terry replied, "The fu.... who made that match."

THE PADDINGTON EXPRESS - TERRY DOWNES

Contributed by Paul Zanon

On 9 May 1936, Luis Firpo fought Saverio Grizzo and Jimmy Wilde fought Domingo Sciaraffia. In other boxing news, a certain Terence Richard Downes was born in Paddington, London.

Downes father, Richard, a mechanic by trade was the first person to teach young Terry the basics, which apparently came in handy for his encounters on the streets of Paddington. However, his skills were honed at Fischer ABC, where he amassed silverware in numerous school tournaments and area championships.

Keen to prepare for one particular bout against Ron Hillier in the semi-finals of a tournament in London, Downes picked up a boxing book, looking for a few essentials pointers. As he was browsing through, he came across a photo of Hillier demonstrating boxing technique. Downes reportedly said, ‘Bloody hell. How am I supposed to beat him? He’s showing me how to fight!’

Despite losing to Hiller, through a dark twist of fate Downes ended up progressing his career in the United States. His 18 year old sister Sylvia, who was in the circus, was involved in a bus accident in 1952 and lost her arm. The Downes family raised money to send Sylvia’s mother to be with her, then Terry and his dad followed. Within no time the family were residing in America. Young Downes was 17 at the time.

Downes continued boxing, initially representing the YMCA, but after gaining victory against a U.S. Marine, he was convinced to join the corps. He fought over 50 times for the Marines all over the U.S. losing only a handful of contests along the way, on points.

As a Marine, Downes won his fair share of silverware, including the Amateur Golden Gloves and the All Services Championship, defeating Pearce Lane. Despite fighting in the Olympic trials, Downes was refused entry onto the U.S. Boxing Team due to not holding U.S. citizenship. Instead, Lane represented the U.S. in the welterweight division at the Olympics in Melbourne in 1956, although he failed to achieve medal status. Aged 89, Lane is still alive today.

With his Olympic dream shattered and an estimated 150 amateur fights to his name, with Downes claiming only four losses, the crowd pleasing sensation returned to the UK and made his debut on 9 April 1957, aged 20 years old. The Paddington Express ran over Peter Longo in the opening session at the Harringay Arena, then 21 days later stopped 38 fight journeyman, Jimmy Lynas in the third round.

By now Downes was managed by Sam Burns, who at the time worked with world renowned promoter Jack Solomons, as his right hand man. However, over the years, Burns joined forces with the likes of Jarvis Astaire, Mike Barrett, Mickey Duff and Harry Levene, guiding many top grade boxers to world title challenges over several decades. With an acute business brain, he acted as a good financial guide to Downes over his career.

Downes next fight could only be described as abysmal matchmaking from Mickey Duff. Only two weeks after the Lynas fight and barely one month into his professional apprenticeship, Downes was pitted against a fearsome young Nigerian called Richard Ihetu, more commonly known in boxing circles as Dick Tiger.

On paper, Tiger brought a 20-8 record to the ring, but all eight of those fights came via points losses and many had been highly debated for years. Duff had chosen Tiger as a stiff test for Downes, but the two fight novice had no business being in the ring with a future two weight world champion. Downes took a one-sided beating at the hands of Tiger and didn’t make the final bell. After the contest, Downes was quoted as saying, ‘I thought, fucking hell they’ve put me in with a giant. Then I realised I was flat on my back looking up at him!’

Bouncing back a mere three weeks after his fifth round defeat, Downes knocked out Alan Dean and in his next 15 contests, Downes improved his record to 16-3, with 13 stoppages. His come forward aggressive style, which earned him almost 400 stiches to his face over the years, was a guaranteed crowd pleaser and on 30 September 1958 he was rewarded with a shot at the British middleweight title.

Only 17 months on from his debut, on 30 September 1958, Downes was back at the Harringay Arena, but this time against an opponent with an impressive 46-3-3 record. Welshman Phil Edwards had held the Welsh Area middleweight title and despite putting up a gutsy performance, was simply worn down by the audacious Londoner in the 13th round.

The same year, Downes married Barbera Clarke. They would remain together until his death, totalling almost 60 years of marriage. They went on to have five children, one of whom became a sports writer and renowned comedian, James McNicholas.

Back to the boxing. Six weeks after being crowned British champion, Downes knocked out Algerian born Frenchman, Mohammed Ben Taibi in three rounds. However, his next four fights wouldn’t indicate a future world champion in the making. With the exception of a seventh round stoppage of Frenchman Andre Davier on 7 July 1959, Downes lost against American, Spider Webb (great name), Frenchman Michel Diouf and more painfully, an eighth round disqualification against John ‘Cowboy’ McCormack (22-1 at the time) on 15 September 1959, losing his British title and also the opportunity to amass the Commonwealth strap. Downes now boasted a professional record of 19-6.

The rematch against McCormack was set up six weeks after the first encounter, but this time, Downes was on blistering form stopping ‘The Cowboy’ in the eighth session and by doing so picking up the British and Commonwealth middleweight titles. Over the next 11 months, Downes clocked up five further victories, four by stoppage. However, it was the win against 107 fight veteran Joey Giardello on 11 October 1960 at Empire Pool, Wembley which gained worldwide acclaim. Many thought cheeky Downes would try to steamroll Giardello, but it was the Londoner’s boxing skill which generated the victory.

Incredibly, despite his 82-18-7 record, Giardello was far from peaking in his career. Six months prior to his clash with Downes he walked away with a split decision draw against Gene Fullmer, for the NBA world middleweight title and three years after his clash with Downes, in 1963, he beat Dick Tiger to become the WBC and WBA world middleweight champion. He held the crowns for two years.

With the media spotlight on Downes, three months after Giardello he packed his bags and headed Stateside to Boston, Massachusetts to take on the reigning middleweight world champion, Paul Pender. The American was fresh off two back to back split decision wins against ring legend, Sugar Ray Robinson and on 14 January 1961 at the Arena, Boston, Pender proved too much for the eager 24 year old Londoner. Stopping Downes in the seventh round, three months later Pender successfully defended his title against ‘The Upstate Onion Farmer’ Carmen Basilio.

Not one to rest on his laurels, while Pender took on Basilio, Downes improved his record by another two stoppage victories, putting him in pole position for another shot at Pender’s world title. Less than six months after their first encounter, Pender made the bold move to travel to the other side of the pond, which didn’t work out as he expected. On 11 July 1961, with an insatiable desire to win, Downes forced Pender into retirement in the ninth round at the Empire Pool Wembley.

While the punters were backing Downes at the bookies, Downes, alongside his manager Burns, invested heavily into the bookmaking industry, opening a string of shops on the back of his newly crowned status. The investment would prove to be more than prudent, providing them both with a lifetime fortune far beyond boxing.

Nine months after being crowned world champion, Downes travelled back to Pender’s backyard for the third and final installment of the rubber match. On 7 April 1962, Pender regained his world title with a debatably close points victory at Boston Garden and retired straight after the fight. After the first two fights Pender realised the risks in standing toe to toe with Downes and opted to use his height and reach to full advantage, suffocating Downes’ attacks.

In the next five months Downes clocked up two further points victories against big name Americans, Don Fullmer and ageing Sugar Ray Robinson, albeit, a humble Downes was the first to acknowledge, ‘I didn’t beat Sugar Ray Robinson. I beat his ghost.’

Over the next two years, Downes won a further five fights, including four by stoppage, before taking on Louisiana’s favourite fighting son, reigning light heavyweight champion Willie Pastrano. Back then, there wasn’t the luxury of super middleweight. You either fought at 160lbs or moved up to 175lbs, which was a gutsy move for Downes because he was far from a natural light heavyweight. Despite only weighing 171lbs on the evening, Downes emptied his tank on 30 November 1964 at King’s Hall, Belle Vue, Manchester and went out on his shield with an eleventh round stoppage at the hands of Pastrano.

Downes retired after that fight at only 28 years old, boasting British, Commonwealth and world titles. With a healthy record of 35-9, Downes stuck to his word and was never lured back by the old boxing adage of ‘one more fight’. Financially he was set with his bookmakers investment and later on owned a car dealership and a nightclub in London.

Downes maintained a strong interest in boxing after retirement and would often be the first port of call for sports commentators when looking for a colourful opinion of a fighter or fight. Despite not publicising his charitable efforts, Downes was a well known figure on the fundraising circuit and in 2012 was justly awarded the BEM (British Empire Medal) for services to sport and philanthropic efforts. Dabbling in film and television appearances, the final curtain came down on the vastly charismatic Downes on 6 October 2017, aged 81. He reportedly died from kidney failure.

July 11th, 1961, Terry Downes defeats Paul Pender for the undisputed world middleweight championship. Pender was a firefighter turned boxer from Brookline Massachusetts, clever boxer, a thinking man's fighter, one of the underrated middleweights from the 1950s. Pender was one tough SOB, I mean we're talking about a guy that broke both hands in a fight against the great Gene Fullmer and somehow finished the fight, and even floored Fullmer before it was over. Pender held two wins over Sugar Ray Robinson and a win over Carmen Basilio, although both Robinson and Basilio were past their best. Nevertheless, Pender was a good fighter, and Pender and Downes fought a trilogy with Pender winning the first and third fights, and Terry Downes winning the second one for the undisputed world middleweight crown.