Emile Griffith and Nino Benvenuti fought three times, one of the greatest trilogies in boxing history, with Benvenuti winning the furst one and becoming the first Italian in boxing history to become middleweight champion, Griffith, great at making adjustments and winning rematches, won the second fight to regain his middleweight crown, and Benvenuti lifted the title back from Griffith in the rubber match. It was a great, hard fought trilogy, and every fight was close.

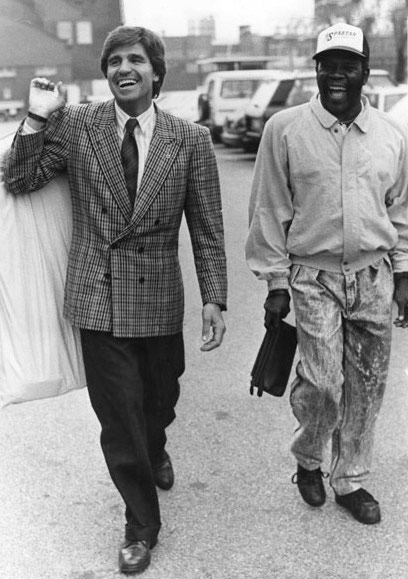

Nino Benvenuti and Emile Griffith walking in Rome, Italy

Benvenuti-Griffith was a trilogy for the ages

By Jack Hirsch

Published Sep 17 2024

By the time the year 1967 rolled around, Emile Griffith was on top of the boxing world. As a former three-time world welterweight champion and current middleweight title holder, Griffith’s credentials put him on a par with many of the all-time greats.

One of the busier fighters of his era, it took a court order to prevent Griffith from being both the world welterweight and middleweight champion simultaneously. Only weighing 151lbs when he dethroned Dick Tiger for the middleweight crown, Griffith could have still made the 147lbs welterweight limit to defend that title.

In succeeding fights, Griffith would frequently weigh-in under the junior middleweight 154lbs limit as well, But there was no serious consideration to him campaigning in that weight class due to the lack of significance it held during that time. But Griffith was doing just fine ruling the middleweights, making two successful title defenses against New Yorker Joey Archer, before agreeing to defend his title against Italy’s Nino Benvenuti on April 17, 1967 at the old Madison Square Garden.

Despite having impressive credentials, Benvenuti was lightly regarded entering the contest, this in large part to the stigma that hung over European fighters at the time. Although they occasionally came to the United States and had success, such as France’s Marcel Cerdan stopping Tony Zale to win the middleweight crown, for the most part the forays of the Europeans did not end well.

That Benvenuti’s challenge was not taken more seriously at the time is baffling on reflection. At the Rome Olympics in 1960, he was voted as the best boxer of the tournament, beating out a teenage phenom named Cassius Clay. Benvenuti was also a former world champion as well, winning the junior middleweight title from fellow Italian Sandro Mazzinghi, then making two defenses of that crown, before dropping it on a split decision to South Korean, Ki Soo Kim in Seoul. Benvenuti had only lost once in 72 fights, and had beaten credible opposition such as Don Fullmer and Denny Moyer among others.

In this age of social media, Benvenuti would have been fully exposed to the public who would recognise the threat he posed to Griffith, but at the time few people attending their fight at Madison Square Garden had seen Nino box. Griffith was another matter. He had fought so many times in Madison Square Garden, that his manager/trainer, Gil Clancy, described it as the house that Griffith built. Griffith was also well known outside of the boxing community primarily because of the ill-fated match with Benny Paret five years previously. Paret’s death had a profound effect on the sport with many calling for it to be abolished due to its brutality. Some said that Griffith was never the same in the ring afterwards, that he eased off on his punches because he was haunted by the spectre of Paret’s death. While it is easy to surmise such a theory, the truth is that Griffith was more of a grinder than a puncher. His keys to victory were a high workrate, his physical strength, and fundamentally being able to do things better than his opponents. As Clancy said, “Griffith did nothing great, but he did everything well.”

Although Griffith knocked Tiger down for the first time in his career during the ninth round of their fight, the Nigerian rebounded and some thought was unfortunate not to be given the decision. The two title defenses against Archer were also close. The first one could have easily gone to Archer, which actually might have aided Griffith’s legacy in that he would then have regained the crown in their rematch instead of just retaining it. A three-peat of the middleweight title to match what he did at welterweight, would have made Griffith truly immortal if he is not considered so already.

Although he was born in the Virgin Islands, Griffith lived and trained in New York, where he continued to reside for the rest of his life. He was a New Yorker and a crowd favorite, but on the night of April 17, 1967 at MSG, Emile was startled by the noise level directed toward his opponent. New York boasted a huge Italian population who came out in force for Italy’s Benvenuti, making themselves heard unlike any other night that Griffith fought. “Nino, Nino, Nino” their voices rose in unison from the rafters all the way down to ringside.

The Garden was rocking. The noise reached a fever pitch when Benvenuti dropped Griffith heavily on his backside in round two. How hurt Griffith was he only knew, but what is indisputable is the stunned look on his face as he lay on the canvas before getting up a few seconds later. It was Benvenuti introducing himself to the American audience at Griffith’s expense.

Benvenuti, 28, spoke no English, but he was oozing with charisma, a matinee idol, handsome, and long hair that was pronounced. He was a boxer-puncher. who liked to dart in and out, not adverse to using tactics that stretched the rules a little, but at the same time would look toward the referee if he felt victimised.

Benvenuti’s strong start had the Garden in an uproar, but disaster nearly struck in the fourth round when Griffith delivered a thunderbolt, a right hand that sent Benvenuti down and sprawling along the ropes. Nino was badly hurt with more than enough time in the round for Griffith to finish him. Later, Griffith would put the blame on himself for Benvenuti escaping the crisis. “I went right hand crazy,” he said. It is hard to fathom what would have become of Benvenuti had he not survived the round. Perhaps he would have regrouped and won the title at a later date, but his career as we know it and his rivalry with Griffith never would have materialized.

From the fifth round on it was basically Benvenuti’s fight. Griffith moved forward, but could never get comfortable. Benvenuti darted in and out, rushing the Virgin Islander who could not get off. When the final bell rang it appeared that Benvenuti had done more than enough to take the title. The judges concurred in scoring it unanimously for him by margins of 10-5, 10-5 and 9-6.

Ring Magazine voted it the ‘Fight of the Year’, but that was more a result of the stir that Benvenuti’s victory caused. The action inside the ring from the fifth round on was not especially exciting. This was reflected by the blow-by-blow account of the legendary broadcaster Don Dunphy. Criticised as to why he did not show a touch more enthusiasm, Dunphy said, “I won’t fake a fight call.”

Italy rejoiced. If Benvenuti was not a national hero in his country before he certainly was now. In 11 days, Muhammad Ali would refuse induction into the United States military. His license to box was suspended. The sport needed a shot in the arm. Benvenuti provided that. He was now a genuine star in his own right, whose victory over Griffith was not regarded as a one-off. The day after beating Griffith, Benvenuti was interviewed alongside Rocky Marciano who said, “Last night I did not see a good fighter, I saw a great one.” Nino was the talk of the boxing world.

It was generally reported that Griffith had taken a beating in the fight. While that might have been a slight stretch, there is no question that his pride was deeply hurt to the point of being bitter. Griffith knew how poorly he had performed by his standards. He had something to prove in the rematch which took place on September 29, 1967 at New York’s Shea Stadium, the big outdoor ballpark that served as the home to the New York Mets and New York Jets.

Benvenuti’s victory in the first fight was decisive enough for people to question how much more Griffith could do to turn the tables in the rematch. Griffith had lost before, but there was a resolve to avenge this defeat like there had never been previously. When asked how he would defeat Benvenuti, Griffith got right to the point. “I’m gonna knock him out,” he said confidently. Clancy wasn’t so sure. Clancy knew that more likely than not they would go to the scorecards again. “I want judges who won’t be influenced by all the chants of Nino, Nino,” he said.

Griffith was more focused the second time around, controlling the match by staying a gentle step ahead of Benvenuti throughout. Griffith would work his way inside where he scored with uppercuts while smothering Benvenuti’s attack. But Benvenuti landed the occasional jarring hook which kept him in the fight. It was not until Griffith dropped Benvenuti in the 14th round that it became apparent that he would regain the title. Yet, according to one scorecard, 7-7-1 he didn’t, but the other two came in at 9-5-1, giving Griffith a well-deserved victory. By the way, the rules at the time said that if a judge had the fighters even at the end of the fight he should break the tie by going to the supplemental point system. Mysteriously, the judge failed to give Griffith credit for the knockdown he scored, making it officially a majority decision instead of a unanimous one. No matter, Griffith rejoiced.

Afterward in his jubilant dressing room Griffith’s mother, a big strong woman, picked up her son and held him in the air like a baby. Emile, who was always a momma’s boy, grinned widely. “I had to show a lot of so-called friends that I was better than Nino,” he said.

Griffith’s victory restored order, not only in the middleweight division where he once again reigned supreme, but in his head-to-head comparison with Nino. As a result, he was favoured to win the rubber match. The new Madison Square Garden (the one of today), opened on March 4, 1968 with a doubleheader featuring Griffith and Benvenuti as the co-main event along with Joe Frazier vs Buster Mathis.

Both Griffith and Frazier set up camp for their respective fights at the Concord Hotel in upstate New York. The two became great friends.

Griffith trained hard as always and was in great form going into the fight. The same could not necessarily be said about Benvenuti.

Interestingly enough, both took a tune-up match in Italy, during the interim. Griffith had little trouble disposing of Italy’s Remo Golfarini in six rounds. Benvenuti struggled, needing to come on in the second half of the match to win a 10-round decision over American, Charley Austin. But Benvenuti remained confident and took issue with those who felt he was decisively beaten by Griffith. “My second fight with Griffith was very close,” he opined.

Clancy had described Griffith as a fighter who did nothing great, but everything well. If Griffith’s greatest asset was his enormous strength, his biggest drawback was his tendency to get lackadaisical from time to time. Admittedly, it drove Clancy crazy. He would try to wake Griffith up from his stupor by slapping him hard across the face as the fighter sat on the stool in the corner. In this day and age, such an action would have evoked a tremendous uproar, but at that time it was not seen as anything outrageous. The men had been together from the time Griffith had started to box as an amateur. They reportedly never had a contract, doing all of their business dealings on a handshake. The two genuinely cared for one another. Clancy’s partner Howie Albert who also served as Griffith’s co manager and cornerman, formed a tight knit unit.

Benvenuti got off to a fast start in the third encounter. He was generally beating Griffith to the punch and was faster on his feet than he was in the last match.

In the ninth round, Benvenuti dropped Griffith in a heap with a right. It was a hard, solid blow that hurt the defending champion. Emile quickly recovered, but at that point everyone knew his title was in serious jeopardy.

At the end of 12 rounds, Benvenuti appeared to have a commanding if not insurmountable lead. Griffith furiously rallied over the last three rounds, creating high drama in the last minute when he hurt Benvenuti with a right that had the challenger reeling. Griffith desperately tried to finish the job, but ran out of time not only in the round, but on the final scorecards, losing a unanimous decision by margins of 8-6-1, 8-6-1, and 7-7-1 (points 9-8 Benvenuti). The decision in Benvenuti’s favour was not controversial, the closeness of the scorecards withstanding. Even Clancy who veteran boxing aficionado Lew Eskin once said never agreed with a decision that went against one of his fighters, did not claim they were hard done by the verdict. Instead, Clancy lamented what took his man so long to get going. Griffith though disagreed, convinced he had won, later saying, “If they had given me the decision, Benvenuti’s fans would have torn down Madison Square Garden.”

A fourth fight was not ruled out, but never quite transpired. The closest it came to happening was the following year when Griffith avenged a highly controversial loss to Philadelphian Stan ‘Kitten’ Hayward. Entering Griffith’s dressing room afterward to help take his gloves off was old friend Benvenuti. Although Griffith won decisively on points, Garden Matchmaker Teddy Brenner felt that he lacked spark. Brenner put off the notion of a fourth fight with Benvenuti until it gradually faded away.

Griffith would go on to score many fine victories in the succeeding years and receive four more cracks at a world title, never winning it. He dropped down to welterweight to challenge the great Jose Napoles for his old welterweight crown and was beaten decisively on points. Twice Carlos Monzon turned back Griffith’s challenges. The first by a 14th round stoppage when Griffith, behind on points, doubled over due to leg cramps. In their rematch, Griffith was beaten on the cards by two, three and four points respectively. According to Clancy, British promoter Mickey Duff peaked at the scorecards before they were announced, then hurried excitedly over to him and said, ‘The old man did it, Griffith is champion again.” Not quite, officially at least.

Afterwards, Monzon said that it was the toughest match of his career. Three years later, when he was on the downside of his career, Griffith’s name was enough to get him one last chance at a world title when he challenged Eckhard Dagge for the WBC junior middleweight title in Germany. Griffith got himself into supreme condition and turned back the clock to an extent, appearing to hold a slight lead at the end of 15 rounds. But Dagge, boxing in his home country, was awarded a majority decision.

After defeating Griffith the second time, Benvenuti performed erratically in non-title matches, losing a couple and boxing a draw, but with the title on the line he was his old self, successfully defending it four times before being knocked out by Monzon in 12 rounds in November of 1970 in Italy. It was a result which no one saw coming. In the rematch, Benvenuti fared worse, being halted in three. That would be his last fight.

Because of the Paret tragedy, Griffith’s legacy will always be linked to him more than any other opponent. Not so for Benvenuti. Griffith was far and away his greatest rival, the one who brought out the best in him, the one who always invoked the warmest memories. Their bond would turn into a lifetime friendship outside of the ring until the day Griffith died in 2013 at the age of 75. So close were the two that Griffith was Benvenuti’s son’s godfather.

Benvenuti would go a step further, periodically flying Griffith to Italy where the two men sat with a crowd of people who watched the tapes of their fights. And, according to Griffith, he had quite a bit of support in Benvenuti’s homeland.

Former world middleweight champion Vito Antuofermo can vouch for that. As a young teenager living in Italy who had not yet laced on a glove, Antuofermo stayed up late to watch the Benvenuti vs Griffith fights. “They were both my idols, maybe Griffith a little more so,” he once told me. Antuofermo never imagined that one day he and Griffith would share a ring at Madison Square Garden and that he would win the cherished middleweight title that both of his idols held.

Obviously, Ali vs Frazier is the greatest trilogy in boxing history. But, aside from that, there has arguably never been another three-fight series in which the fighters were as evenly matched and stirred the emotions of the public as did Benvenuti and Griffith.

Emile Griffith and Nino Benvenuti became good friends during their trilogy, going through ring wars together will sometimes do that, it's a bond that's forged in fire, you can't really understand it unless you've been in a ring war.

One more series I want to talk about was the Emile Griffith-Carlos Monzon series, they fought twice but Griffith was past his prime. Yet despite being past his prime, he damn near took the middleweight title from Monzon. If you're not familiar with Carlos Monzon, he's one of the greatest middleweights in history, top three, right there with Hagler, Greb, Robinson, he ruled the middleweight division with an iron fist for seven years in the 1970s, making 14 defenses of his title. Carlos Monzon was from Argentina, but he was a violent bastard of a man, he was evil, he physically beat his girlfriends and even murdered his wife by throwing her off a balcony, she actually shot him before he threw her off the balcony but he survived the shooting. He was charged for her death, convicted, and sentenced to 11 years in prison. He died in a car crash in 1995 while on furlough from prison. Carlos Monzon was brilliant in the ring, he was tall and had a long reach, an iron chin, a phenomenal ring technician, but a real POS excuse of a man. Anyway, Emile Griffith made another bold as hell move by trying to take Monzon's crown, Griffith was past prime but he went for it anyway. Griffith was at a disadvantage against the taller and rangier Monzon, he made it to the 14th round in the first fight before being stopped, but Griffith was never one to give up, and he was great at making adjustments and winning rematches, so he took another crack at Monzon, and damn near took Monzon's crown but gassed out at the end. Despite losing the rematch, he took Monzon the distance, it was one of Griffith's greatest moments, a past prime, smaller, natural welterweight almost taking down one of the top three middleweights of all-time, not too shabby.

The great Carlos Monzón made his seventh defense of the middleweight championship with a tough 15 round unanimous decision in a rematch with former champ Emile Griffith at the Stade Louis II in Fontvieille, Monaco in 1973.

Griffith, former welterweight and middleweight champion, did well attacking Monzón in their first bout at Estadio Luna Park in Buenos Aires a few years earlier. But he had serious issues with Monzón's reach and style, as most did.

Monzón rattled off a few defenses after their first bout, including righting a wrong in a rematch with Bennie Briscoe. Griffith had clearly lost a step, but he'd gotten enough wins in the meanwhile to justify a rematch.

A ringside report said:

"Middleweight champion Carlos Monzon of Argentina struggled through 10 rounds, often outboxed and outpunched, but turned on a late spurt Saturday night to beat Emile Griffith and deprive him of a sixth world title.

Monzon, 31, staggered in the 8th round by a Griffith right, cut the 35 year old New Yorker in the 14th round, culminating the rush that saved his title. In the 8th round, when Griffith seemed to be leading on points, Monzon scored a good left-right combination but was staggered by a Griffith right hand when he sought to press the attack.

Griffith was unable to take advantage of the situation and two rounds later showed signs of tiredness for the first time. There were no knockdowns."

After the final bell, Monzón ignored Griffith, who tried to embrace or at least salute his opponent. The announcement of a decision to the champion was met with a mixed reaction from the crowd of about 10,000.

"It was the most difficult fight of my career," Monzón said. "I thought it was a draw up to the 11th. Griffith is very strong, but I won."

"It was a rough decision," Griffith said. "I really thought I became champion again."

This is an interview conducted with Emile Griffith in 2001. I always love to read what the legends have to say about their careers, their battles, their opponents.

Interview: Emile Griffith

Ike Enwereuzor

Emile Griffith began his professional debut June 2, 1958 as he won a fourth round decision over Joe Parham. He was first introduced to amateur boxing by his uncle in St Thomas, West Indies when he was 18 years old. Six time champion Emile Griffith was inducted into the International Hall of fame in 1990 and world hall of fame.

IE: I'm here with 6 time champ..What are you doing these days?

EG: I've been busy training fighters and attending special events

IE: You're considered as one of the greatest middleweight of our time. What did you think of Hopkins-Trinidad fight, if you watch it?

EG: Yes, I watched the fight. Hopkins did well but I don't think I saw the same Trinidad I know. I think Trinidad fought good too but Hopkins was the better man that night. If they ever fight again I think Trinidad will get him this time. Maybe Trinidad underestimated Hopkins or he didn't train hard enough.

IE: Why did you decide to box?

EG: I wanted to play Baseball but I was small to play. Howard Albert asked if I ever boxed. He took me to the gym department parks on 28th Street, NY. After that, I would go over to the gym after work to workout with the guys and I get beat up but I stayed around to learn. I won the Golden Gloves in 1956 then turn pro in 1958.

IE: What do you remember from your pro debut?

EG: It's been a long time. It was at Old St Nicks in New York City and I beat the guy by decision.

IE: Your toughest professional fight?

EG:My toughest fight was with Dick Tiger. Nino was tough too and Carlos Monzon was too. I was lucky to beat Tiger. I always say I was lucky to win all my fight but I trained very hard for all of them. Kids today don't train as hard as we did those days. They want it easy but it can't work if you don't prepare very hard. This is what I teach my fighters.

IE: Where did you use to camp for your fights?

EG: We use to go Upstate New York, called Concord Hotel in Caskills. We took training very serious, I would be practizing moves, body punches, right hand and throwing left hooks. My trainer Gill Chancy was a good trainer and one of the best in the business.

IE: How would you compare the fight to your fights with Dick Tiger?

EG: Tiger was my good friend, we use to spar together at Gleason gym in Bronx, NY then. Few years later I got a chance to fight him, I guess that help me to beat him because I knew his style. I learn a lot from Tiger and learn from me too. When we sparred together I was like 147 and he was a full middleweight. We use to go to central park together to do our road walk too. My two fights with Dick Tiger was a heal of a fight. I think we had a tougher fight than Hopkins-Trinidad.

IE: Your thoughts on Tyson-Nelsen bout?

EG:Are you making jokes, Ike? Tyson fought a white guy who was strong but can't fight, Tyson should have stopped him earlier. He kept holding Tyson but Ref. Steve Smoger just kept breaking them up. Mike needs more work before he fights for any title.

IE: What else can you tell me about your meetings with Dick Tiger?

EG : I was like a boxer, he was a puncher and boy, Dick Tiger can hit. I was fast and my trainer Gill Chancy use to tell me not to let my opponent throw shots first at me, I should be the one throwing first. I was the better man that night.

IE: Which fight of your career was your highest payday?

EG: It was my fight with Nino Benvenuti. I made almost quarter of a million.

IE: Can you compare you fights with Nino Benvenuti

EG: We had three good fights. He was tough on all 3 fights, 2 in 1967 & third one in the garden took place in 1968 but I was a little tougher. I think I won all our fights but they gave me only the second one. One of the fight with him I slipped but they called it a knock down and we protected.

IE: How would you compare the old Madison Square Garden to the new?

EG: The old Garden was good but now we have something better and larger. Now, they have various major events there like Music, basketball, Hockey, Boxing and more.

IE: How did you feel to capture your first title against Benny Paret on April 1, 1961?

EG: It was a great fight for me and I was a happy man. I knocked him out in 13th round and I did a back flip in the ring after I won the title. I felt like I owned the whole world. It was definitely a great feeling to win the title. I received a lot of congratulations from my sparring partners, many fans, my baseball team (The Griffs) family & friends.

IE: Tell us about "The Griffs" ?

EG: It was a baseball team I formed to teach kids how to play. I started it after I turned professional in early 1960's.

IE: What was it like to be inducted into International Hall of Fame in 1990?

EG: It was fun. A lot of my friends, New York Commissioners were there. It was very exciting moment for me and my family.

IE: Your most memorable moment of your career would be...?

EG: My third fight with Benny Paret....... Oh my God, it was a disaster. I almost lost my career. Benny passed away, may his soul R.I.P after that fight, I didn't want to fight any more. My mind can't get me to fight. I was getting hate mails from Cubans calling me a murderer but I also got positive mails from fans who cared about me. The fans wrote to me saying it wasn't my fault, that was boxing. I even received a mail from a fan who's a truck driver he told me how a little boy ran in front of his truck and he couldn't save the kid's life. He said, that never made him to quit his job. It was an accident after receiving a lot of mail as such my trainer encouraged me to get back in the ring so I tried to go back. The advise and support from fans made me get back into it. They said, we love you and want to see you fight again champ. I didn't know I was much appreciated till then.

IE: Can you please describe your fights with Carlos Monzon?

EG: He was taller and had a longer reach than so it was hard to get into him but I do get in, I made him feel my punches.

IE: Tell us about your Fight with Hurricane Carter?

EG: They did a movie on him. I lost to him but it's time for Emile. I trained Wesley Snipes for a movie "Street of Gold" and I was show a little in that movie too. Wesley knows his stuff and I think he could play my role very well.

IE: Your favorite fighters during your era would be ....?

EG: I like "Sugar" Ray Robinson, I use to do road walks with him and I sparred with him one at Gleason Gym in the Bronx. Joe Louis, I met him few times in Las Vegas and New York. Archie Moore was a very good man, he showed me a lot in the gym too. One thing I liked about him was that he never show off.

IE: What's your impression of Jose Torres?

EG: Another friend, he was the captain of the Golden Gloves and we sparred a lot then. I learn a lot from him though we always tried to out run each other.

IE: Your advise to those who may be interested in becoming a boxer?

EG: Firstly, start with running, get in shape but they should leave me alone if they are not doing well in school. I was lucky to make it it's not going to be easy for anyone who decides to box. If they find someone who cares they must constantly listen to trainer and do what they ask you to do.

IE: Where are you training fighters?

EG: I've my gym at gleason gym and I go to other gyms too.

This is one of my favorite photos of Emile Griffith, I actually own this photo. He was always training hard, in phenomenal shape, living the life, boxing isn't just a sport, it's a way of life, and if you're not 150% dedicated and in shape, you won't last long in the hurt business.

Stranger than Fiction: Mexican Joe Rivers, who controversially lost a double-knockout title fight to Ad Wolgast in 1912, was rediscovered by a journalist in late-1950s Los Angeles living alone in a windowless room, his only possession a 200-year-old violin which he played daily.

During his career from 1910 to 1923 they called him Mexican Joe Rivers, "The Lethal Latin." A Californian phenom, he burned his way through the bantamweight and lightweight ranks and was part of the notorious double-knockdown bout with Ad Wolgast, "The Michigan Wildcat", in which both men went down simultaneously but Wolgast was helped up by the ref while Rivers was counted out. Rumors had Rivers dying in WW1 on the SS Tuscania but in 1955 a sportswriter for the LA Times named Frank Finch heard about a Joe Rivers who had been hospitalized and recalled the name.

Sure enough, it was Mexican Joe Rivers, living in a little room on West Second Street with no windows. He wasn't a Mexican, he explained, to the first man who ever listened. His name was Jose Ybarra and he was a 4th-generation Californian of Spanish/Native blood. Once upon a time a boxing promoter had asked him where he lived and he'd replied, "Down by the river" so he became Joe Rivers and then a Mexican because Mexicans came to fights.

He'd earned a quarter million dollars in the ring, had dozens of suits, a touring car with his initials on the side, bought his mother a nice home. All gone now. Kids like him in the fight game had no idea what to do when the money came in, and nine times out of ten the people around them who understood money were only there to take it away.

His only possession of any value was his father's 200 year-old violin. He played it every day.

“I guess I had a million friends,” he said. "Gone now, most of them. The others - they don’t come around much anymore.”

Joe Louis made the 16th successful defense of his world heavyweight title with a ninth-round stoppage of Blue island, Illinois' Tony Musto in Saint Louis, Missouri in 1941. Musto was still on his feet and still willing to fight when referee Arthur Mercante had seen enough after a methodical beating by the champion. Never before knocked down in thirty-nine fights, Musto found himself on the canvas in the third round. But the sturdy challenger bounced up and proceeded to present stubborn opposition to Louis. Musto's right eye required stitches when the fight was over.

35 years ago, 73-year old Billy Conn, "The Pittsburgh Kid", walked into a convenience store for some coffee only to find it being robbed by 27-year old Nick Conyer.

Conn rushed the robber and in his words, “fixed him” with his favorite punch, a left hook. What a legend.

Maciej Sulecki wasn’t exactly enjoying all the punches to the head that Diego Pacheco was dishing out at him in August 2024, but he could take them. Across 14 years and 35 fights as a pro, the Polish super middleweight had acquired all the veteran savvy needed to roll with shots, buy time when buzzed, use his legs and get through every sticky situation he had ever been in. But when Pacheco put the full torque of his 6-foot-4 frame into a whipsaw left hand that landed just under the right elbow 41 seconds into the sixth round, there was nothing Sulecki could do. Veteran wiles didn’t count for much. Steely resolve didn’t do him any good. His body spun around 270 degrees clockwise as it crumpled. Sulecki went into the fetal position. Then he rolled onto his back, and he couldn’t lift any part of himself off the canvas before referee Ray Corona counted 10. Body-shot knockouts aren’t usually as eye-popping as a crack to the jaw that renders a fighter unconscious, a reality reflected in the fact that only once in the 35 years that “The Ring” magazine has been naming a Knockout of the Year has that honor gone to a pure body-shot KO. But body-shot knockouts are beautiful in their own way. There’s an accompanying agony on the face of the victim that we don’t get with head shots. And there’s a cerebral appeal to a boxer going downstairs to end matters when faced with a stubborn opponent who can take everything being dished out above the neck – as Sulecki, who had never been stopped before, did for a little over five rounds.

Zora "Bell" Folley was a top 10 ranked heavyweight contender for eleven years in a row from 1956 to 1966 and a nine-time top 5 contender throughout his career, reaching a peak as number 1 contender in 1959. He was Mr. Consistency, every time you opened a Ring magazine between 1956 and 1966, his name was right there in the top 10 heavyweights. Born in Dallas, Texas, and raised in Chandler, Arizona, Zora Folley’s journey to the boxing ring began in the U.S. Army. It was during his military service that he first laced on a pair of gloves, setting in motion a career that would see him become one of the most respected heavyweights of his era. Folley was a decorated Korean War veteran who almost lost toes to frostbite while serving. In 1960 in a showdown with Sonny Liston, Folley Entered the bout with a record of 50-3-2. But after being dropped early in the second round, he made the bold decision to fight fire with fire – only to be floored again and stopped in the third. Despite the setback, Folley carved out a very respectable career and resume. In his prime, Folley was a superb technician: a slick, intelligent boxer with good power. He beat fighters such as Eddie Machen, George Chuvalo, Oscar Bonavena, Henry Cooper, world light-heavyweight champion Bob Foster, Nino Valdez, Doug Jones, Johnny Summerlin, Henry Clark, Mike DeJohn, Bob Cleroux and drew against Karl Mildenberger. Folley fought once for the world heavyweight title, losing to Muhammad Ali in March 1967. Tragically, Folley died in 1972 at just 41 years old, after striking his head on the edge of a swimming pool at a motel in Tucson, Arizona in unexplained circumstances. Though his death sparked speculation and conspiracy theories, it was officially ruled an accident.

Zora Folley was something else, any true boxing fan respects the hell out of him. He had 9 children, a genuinely good human being, brave as can be, one heck of a fighter, it's sad the way his life tragically ended so young. Great book about Folley right here, and an article going a bit more into his life.

Zora Folley

Legendary Contender

Zora Folley is a name that often comes up when discussing the golden era of heavyweight boxing, yet he remains somewhat underappreciated by the broader public. An elegant boxer known for his technical skills, sportsmanship, and the respect he earned from peers, Folley was one of the most feared and respected heavyweight contenders of the 1950s and 1960s. His quiet demeanor outside the ring contrasted with his sharp skills within it, earning him the reputation of being a 'gentleman boxer.' This article delves into the life and career of Zora Folley, a man whose legacy in the world of heavyweight boxing deserves far more recognition.

Early Life and Military Service

Born on May 27, 1931, in Dallas, Texas, Zora Folley grew up during an era of racial segregation, economic hardship, and societal challenges. His family moved to Chandler, Arizona, where he would develop a passion for boxing. However, his entry into the sport was delayed by a stint in the U.S. Army, where Folley began his boxing career in earnest.

Folley’s time in the military was not just a diversion from his civilian life—it was the crucible where his boxing skills were forged. While stationed in Japan, he participated in military boxing tournaments, sharpening his natural abilities and gaining attention for his crisp jab and polished technique. Upon his discharge, Folley returned to the U.S., determined to pursue a professional boxing career.

Early Career and Rising Through the Ranks

Zora Folley made his professional debut on July 9, 1953, defeating Jimmy Ingram by decision. The early years of his career were characterized by a meteoric rise through the ranks, with Folley displaying an elegant, textbook boxing style. He had a composed demeanor in the ring, relying on his jab, defensive skills, and technical precision. Unlike some of the other heavyweights of his era, who were brawlers or power punchers, Folley preferred to box smart, picking apart his opponents with patience and strategy.

Throughout the 1950s, Folley compiled an impressive record, defeating notable fighters such as Bob Foster, Oscar Bonavena, Henry Cooper, Nino Valdes, Eddie Machen, and George Chuvalo. His victories often came through his ability to outthink and outmaneuver his opponents, rather than through brute force. Folley’s fight against Eddie Machen in 1958 was particularly significant, as Machen was considered one of the top contenders at the time. Folley’s victory solidified his place among the elite in the heavyweight division.

Style and Approach

Folley's style was a reflection of his personality: calm, methodical, and respectful. He had one of the best jabs in the heavyweight division and was often described as a "complete" fighter. He had solid defensive instincts, good movement, and could punch with power when needed, though he often opted for a more tactical approach. Folley was a master at controlling the pace of a fight, keeping his opponents off balance with his jab and footwork.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Folley was not a trash-talker or showman. He was a disciplined athlete who let his skills do the talking. His quiet professionalism earned him the respect of both fans and fellow fighters. Muhammad Ali, after fighting Folley, commented on how much respect he had for him, calling Folley a "good boxer" and a "gentleman."

The Championship Pursuit

Despite his success, Zora Folley found it difficult to secure a title shot during the prime of his career. The heavyweight division in the 1950s and 1960s was packed with talent, and Folley, despite being highly ranked, often found himself overlooked in favor of more marketable fighters. His steady, no-frills style did not capture the public's imagination the way fighters like Floyd Patterson or Sonny Liston did.

Folley’s championship ambitions remained unfulfilled throughout much of the 1950s, but his persistence paid off when he finally got his chance at the heavyweight title in 1967. By this time, Muhammad Ali was the reigning champion, and Folley was seen as a seasoned veteran who had earned his shot. However, Folley was also past his prime by this point. At 34 years old, he was no longer the sharp, quick boxer who had dominated much of the previous decade.

The Fight with Muhammad Ali

On March 22, 1967, Zora Folley stepped into the ring with Muhammad Ali at Madison Square Garden for the heavyweight championship. Ali, at the peak of his career, was known for his speed, reflexes, and brashness, while Folley was seen as the underdog, albeit a dangerous one. Ali, who typically engaged in pre-fight verbal sparring with his opponents, refrained from doing so with Folley, showing respect for the older fighter.

The fight itself was a testament to Folley's technical ability, but it also highlighted the gap in physical prowess between the two men. Ali's speed and agility proved too much for the aging Folley, and in the seventh round, Ali knocked him out with a powerful right hand. Folley fought valiantly, but the fight marked the end of his dream to win the heavyweight title. Still, he earned admiration for his performance and the dignified way he handled defeat.

Life After Boxing

After the Ali fight, Zora Folley continued to box but never regained his position as a top contender. He fought sporadically, winning some and losing others, before retiring in 1970 with a professional record of 79 wins, 11 losses, and 6 draws. His career was marked by victories over some of the best heavyweights of his era, and although he never won a world title, he was consistently ranked among the top contenders for much of his career.

Outside of the ring, Folley was a devoted family man. He had ten children and was known for his charitable work and involvement in his community. Unlike many fighters of his era, Folley managed his finances well and avoided the pitfalls of fame and fortune that claimed so many of his peers.

Tragic Death

Tragically, Zora Folley’s life came to an untimely end on July 7, 1972, under mysterious circumstances. He was found dead in a swimming pool in Tucson, Arizona, after what was described as a freak accident. The official cause of death was listed as drowning, but questions have remained about the circumstances surrounding his death. Some have speculated foul play, though no definitive evidence has ever emerged to support these claims.

Legacy

Zora Folley’s legacy in boxing is that of a consummate professional, a gentleman, and a fighter who never quite got his due. His technical prowess, intelligence in the ring, and sportsmanship set him apart from many of his contemporaries. He fought in one of the most competitive eras in heavyweight history and held his own against some of the greatest fighters of all time.

Though he never won the heavyweight title, Zora Folley’s career is a reminder that greatness in boxing is not always measured in championships. His longevity, his skill, and his integrity as a person and a fighter are what make him a legend in the sport. For those who study boxing history, Zora Folley is remembered as one of the finest heavyweights never to win the crown, a testament to the fact that even in a sport often dominated by loud personalities and trash talk, quiet excellence can leave a lasting legacy.

Gosh, honestly, looking at Zora Folley's resume and overall career, I think he should be in the Hall of Fame, just a solid fighter. It's ridiculous to be ranked in the top 10 as long as he was, eleven straight years, that's absurd. There are fighters in the Hall right now with less impressive resumes than Folley.

This is an interesting incident that took place right before Zora Folley and Muhammad Ali were about to fight in 1967. They were both out training, jogging in Central Park, and they just happened to encounter each other. Of course Ali being Ali just couldn't help himself but to start talking trash to Folley and a bit of a scuffle broke out. Drew "Bundini" Brown is pictured in the middle separating them, and Jimmy Ellis, a great fighter himself, is in the background looking on.

Panama's Eusebio Pedroza, aka "El Alacran" which means "The Scorpion", former world featherweight champion. He successfully defended his WBA featherweight title 19 times in 7 years between 1978 - 1985. Unlike boxers today Pedroza was a very active champion. Known for his sharp jab, he could outbox his opponents when he wanted to or end the fight prematurely with a rain of hard blows. He was known for getting stronger in the later rounds of a fight, a quality that made him a formidable foe, he was nearly unbeatable in the final third of a fifteen round ring duel.

Comments

Emile Griffith and Nino Benvenuti fought three times, one of the greatest trilogies in boxing history, with Benvenuti winning the furst one and becoming the first Italian in boxing history to become middleweight champion, Griffith, great at making adjustments and winning rematches, won the second fight to regain his middleweight crown, and Benvenuti lifted the title back from Griffith in the rubber match. It was a great, hard fought trilogy, and every fight was close.

Nino Benvenuti and Emile Griffith walking in Rome, Italy

Benvenuti-Griffith was a trilogy for the ages

By Jack Hirsch

Published Sep 17 2024

By the time the year 1967 rolled around, Emile Griffith was on top of the boxing world. As a former three-time world welterweight champion and current middleweight title holder, Griffith’s credentials put him on a par with many of the all-time greats.

One of the busier fighters of his era, it took a court order to prevent Griffith from being both the world welterweight and middleweight champion simultaneously. Only weighing 151lbs when he dethroned Dick Tiger for the middleweight crown, Griffith could have still made the 147lbs welterweight limit to defend that title.

In succeeding fights, Griffith would frequently weigh-in under the junior middleweight 154lbs limit as well, But there was no serious consideration to him campaigning in that weight class due to the lack of significance it held during that time. But Griffith was doing just fine ruling the middleweights, making two successful title defenses against New Yorker Joey Archer, before agreeing to defend his title against Italy’s Nino Benvenuti on April 17, 1967 at the old Madison Square Garden.

Despite having impressive credentials, Benvenuti was lightly regarded entering the contest, this in large part to the stigma that hung over European fighters at the time. Although they occasionally came to the United States and had success, such as France’s Marcel Cerdan stopping Tony Zale to win the middleweight crown, for the most part the forays of the Europeans did not end well.

That Benvenuti’s challenge was not taken more seriously at the time is baffling on reflection. At the Rome Olympics in 1960, he was voted as the best boxer of the tournament, beating out a teenage phenom named Cassius Clay. Benvenuti was also a former world champion as well, winning the junior middleweight title from fellow Italian Sandro Mazzinghi, then making two defenses of that crown, before dropping it on a split decision to South Korean, Ki Soo Kim in Seoul. Benvenuti had only lost once in 72 fights, and had beaten credible opposition such as Don Fullmer and Denny Moyer among others.

In this age of social media, Benvenuti would have been fully exposed to the public who would recognise the threat he posed to Griffith, but at the time few people attending their fight at Madison Square Garden had seen Nino box. Griffith was another matter. He had fought so many times in Madison Square Garden, that his manager/trainer, Gil Clancy, described it as the house that Griffith built. Griffith was also well known outside of the boxing community primarily because of the ill-fated match with Benny Paret five years previously. Paret’s death had a profound effect on the sport with many calling for it to be abolished due to its brutality. Some said that Griffith was never the same in the ring afterwards, that he eased off on his punches because he was haunted by the spectre of Paret’s death. While it is easy to surmise such a theory, the truth is that Griffith was more of a grinder than a puncher. His keys to victory were a high workrate, his physical strength, and fundamentally being able to do things better than his opponents. As Clancy said, “Griffith did nothing great, but he did everything well.”

Although Griffith knocked Tiger down for the first time in his career during the ninth round of their fight, the Nigerian rebounded and some thought was unfortunate not to be given the decision. The two title defenses against Archer were also close. The first one could have easily gone to Archer, which actually might have aided Griffith’s legacy in that he would then have regained the crown in their rematch instead of just retaining it. A three-peat of the middleweight title to match what he did at welterweight, would have made Griffith truly immortal if he is not considered so already.

Although he was born in the Virgin Islands, Griffith lived and trained in New York, where he continued to reside for the rest of his life. He was a New Yorker and a crowd favorite, but on the night of April 17, 1967 at MSG, Emile was startled by the noise level directed toward his opponent. New York boasted a huge Italian population who came out in force for Italy’s Benvenuti, making themselves heard unlike any other night that Griffith fought. “Nino, Nino, Nino” their voices rose in unison from the rafters all the way down to ringside.

The Garden was rocking. The noise reached a fever pitch when Benvenuti dropped Griffith heavily on his backside in round two. How hurt Griffith was he only knew, but what is indisputable is the stunned look on his face as he lay on the canvas before getting up a few seconds later. It was Benvenuti introducing himself to the American audience at Griffith’s expense.

Benvenuti, 28, spoke no English, but he was oozing with charisma, a matinee idol, handsome, and long hair that was pronounced. He was a boxer-puncher. who liked to dart in and out, not adverse to using tactics that stretched the rules a little, but at the same time would look toward the referee if he felt victimised.

Benvenuti’s strong start had the Garden in an uproar, but disaster nearly struck in the fourth round when Griffith delivered a thunderbolt, a right hand that sent Benvenuti down and sprawling along the ropes. Nino was badly hurt with more than enough time in the round for Griffith to finish him. Later, Griffith would put the blame on himself for Benvenuti escaping the crisis. “I went right hand crazy,” he said. It is hard to fathom what would have become of Benvenuti had he not survived the round. Perhaps he would have regrouped and won the title at a later date, but his career as we know it and his rivalry with Griffith never would have materialized.

From the fifth round on it was basically Benvenuti’s fight. Griffith moved forward, but could never get comfortable. Benvenuti darted in and out, rushing the Virgin Islander who could not get off. When the final bell rang it appeared that Benvenuti had done more than enough to take the title. The judges concurred in scoring it unanimously for him by margins of 10-5, 10-5 and 9-6.

Ring Magazine voted it the ‘Fight of the Year’, but that was more a result of the stir that Benvenuti’s victory caused. The action inside the ring from the fifth round on was not especially exciting. This was reflected by the blow-by-blow account of the legendary broadcaster Don Dunphy. Criticised as to why he did not show a touch more enthusiasm, Dunphy said, “I won’t fake a fight call.”

Italy rejoiced. If Benvenuti was not a national hero in his country before he certainly was now. In 11 days, Muhammad Ali would refuse induction into the United States military. His license to box was suspended. The sport needed a shot in the arm. Benvenuti provided that. He was now a genuine star in his own right, whose victory over Griffith was not regarded as a one-off. The day after beating Griffith, Benvenuti was interviewed alongside Rocky Marciano who said, “Last night I did not see a good fighter, I saw a great one.” Nino was the talk of the boxing world.

It was generally reported that Griffith had taken a beating in the fight. While that might have been a slight stretch, there is no question that his pride was deeply hurt to the point of being bitter. Griffith knew how poorly he had performed by his standards. He had something to prove in the rematch which took place on September 29, 1967 at New York’s Shea Stadium, the big outdoor ballpark that served as the home to the New York Mets and New York Jets.

Benvenuti’s victory in the first fight was decisive enough for people to question how much more Griffith could do to turn the tables in the rematch. Griffith had lost before, but there was a resolve to avenge this defeat like there had never been previously. When asked how he would defeat Benvenuti, Griffith got right to the point. “I’m gonna knock him out,” he said confidently. Clancy wasn’t so sure. Clancy knew that more likely than not they would go to the scorecards again. “I want judges who won’t be influenced by all the chants of Nino, Nino,” he said.

Griffith was more focused the second time around, controlling the match by staying a gentle step ahead of Benvenuti throughout. Griffith would work his way inside where he scored with uppercuts while smothering Benvenuti’s attack. But Benvenuti landed the occasional jarring hook which kept him in the fight. It was not until Griffith dropped Benvenuti in the 14th round that it became apparent that he would regain the title. Yet, according to one scorecard, 7-7-1 he didn’t, but the other two came in at 9-5-1, giving Griffith a well-deserved victory. By the way, the rules at the time said that if a judge had the fighters even at the end of the fight he should break the tie by going to the supplemental point system. Mysteriously, the judge failed to give Griffith credit for the knockdown he scored, making it officially a majority decision instead of a unanimous one. No matter, Griffith rejoiced.

Afterward in his jubilant dressing room Griffith’s mother, a big strong woman, picked up her son and held him in the air like a baby. Emile, who was always a momma’s boy, grinned widely. “I had to show a lot of so-called friends that I was better than Nino,” he said.

Griffith’s victory restored order, not only in the middleweight division where he once again reigned supreme, but in his head-to-head comparison with Nino. As a result, he was favoured to win the rubber match. The new Madison Square Garden (the one of today), opened on March 4, 1968 with a doubleheader featuring Griffith and Benvenuti as the co-main event along with Joe Frazier vs Buster Mathis.

Both Griffith and Frazier set up camp for their respective fights at the Concord Hotel in upstate New York. The two became great friends.

Griffith trained hard as always and was in great form going into the fight. The same could not necessarily be said about Benvenuti.

Interestingly enough, both took a tune-up match in Italy, during the interim. Griffith had little trouble disposing of Italy’s Remo Golfarini in six rounds. Benvenuti struggled, needing to come on in the second half of the match to win a 10-round decision over American, Charley Austin. But Benvenuti remained confident and took issue with those who felt he was decisively beaten by Griffith. “My second fight with Griffith was very close,” he opined.

Clancy had described Griffith as a fighter who did nothing great, but everything well. If Griffith’s greatest asset was his enormous strength, his biggest drawback was his tendency to get lackadaisical from time to time. Admittedly, it drove Clancy crazy. He would try to wake Griffith up from his stupor by slapping him hard across the face as the fighter sat on the stool in the corner. In this day and age, such an action would have evoked a tremendous uproar, but at that time it was not seen as anything outrageous. The men had been together from the time Griffith had started to box as an amateur. They reportedly never had a contract, doing all of their business dealings on a handshake. The two genuinely cared for one another. Clancy’s partner Howie Albert who also served as Griffith’s co manager and cornerman, formed a tight knit unit.

Benvenuti got off to a fast start in the third encounter. He was generally beating Griffith to the punch and was faster on his feet than he was in the last match.

In the ninth round, Benvenuti dropped Griffith in a heap with a right. It was a hard, solid blow that hurt the defending champion. Emile quickly recovered, but at that point everyone knew his title was in serious jeopardy.

At the end of 12 rounds, Benvenuti appeared to have a commanding if not insurmountable lead. Griffith furiously rallied over the last three rounds, creating high drama in the last minute when he hurt Benvenuti with a right that had the challenger reeling. Griffith desperately tried to finish the job, but ran out of time not only in the round, but on the final scorecards, losing a unanimous decision by margins of 8-6-1, 8-6-1, and 7-7-1 (points 9-8 Benvenuti). The decision in Benvenuti’s favour was not controversial, the closeness of the scorecards withstanding. Even Clancy who veteran boxing aficionado Lew Eskin once said never agreed with a decision that went against one of his fighters, did not claim they were hard done by the verdict. Instead, Clancy lamented what took his man so long to get going. Griffith though disagreed, convinced he had won, later saying, “If they had given me the decision, Benvenuti’s fans would have torn down Madison Square Garden.”

A fourth fight was not ruled out, but never quite transpired. The closest it came to happening was the following year when Griffith avenged a highly controversial loss to Philadelphian Stan ‘Kitten’ Hayward. Entering Griffith’s dressing room afterward to help take his gloves off was old friend Benvenuti. Although Griffith won decisively on points, Garden Matchmaker Teddy Brenner felt that he lacked spark. Brenner put off the notion of a fourth fight with Benvenuti until it gradually faded away.

Griffith would go on to score many fine victories in the succeeding years and receive four more cracks at a world title, never winning it. He dropped down to welterweight to challenge the great Jose Napoles for his old welterweight crown and was beaten decisively on points. Twice Carlos Monzon turned back Griffith’s challenges. The first by a 14th round stoppage when Griffith, behind on points, doubled over due to leg cramps. In their rematch, Griffith was beaten on the cards by two, three and four points respectively. According to Clancy, British promoter Mickey Duff peaked at the scorecards before they were announced, then hurried excitedly over to him and said, ‘The old man did it, Griffith is champion again.” Not quite, officially at least.

Afterwards, Monzon said that it was the toughest match of his career. Three years later, when he was on the downside of his career, Griffith’s name was enough to get him one last chance at a world title when he challenged Eckhard Dagge for the WBC junior middleweight title in Germany. Griffith got himself into supreme condition and turned back the clock to an extent, appearing to hold a slight lead at the end of 15 rounds. But Dagge, boxing in his home country, was awarded a majority decision.

After defeating Griffith the second time, Benvenuti performed erratically in non-title matches, losing a couple and boxing a draw, but with the title on the line he was his old self, successfully defending it four times before being knocked out by Monzon in 12 rounds in November of 1970 in Italy. It was a result which no one saw coming. In the rematch, Benvenuti fared worse, being halted in three. That would be his last fight.

Because of the Paret tragedy, Griffith’s legacy will always be linked to him more than any other opponent. Not so for Benvenuti. Griffith was far and away his greatest rival, the one who brought out the best in him, the one who always invoked the warmest memories. Their bond would turn into a lifetime friendship outside of the ring until the day Griffith died in 2013 at the age of 75. So close were the two that Griffith was Benvenuti’s son’s godfather.

Benvenuti would go a step further, periodically flying Griffith to Italy where the two men sat with a crowd of people who watched the tapes of their fights. And, according to Griffith, he had quite a bit of support in Benvenuti’s homeland.

Former world middleweight champion Vito Antuofermo can vouch for that. As a young teenager living in Italy who had not yet laced on a glove, Antuofermo stayed up late to watch the Benvenuti vs Griffith fights. “They were both my idols, maybe Griffith a little more so,” he once told me. Antuofermo never imagined that one day he and Griffith would share a ring at Madison Square Garden and that he would win the cherished middleweight title that both of his idols held.

Obviously, Ali vs Frazier is the greatest trilogy in boxing history. But, aside from that, there has arguably never been another three-fight series in which the fighters were as evenly matched and stirred the emotions of the public as did Benvenuti and Griffith.

Some great shots from the Griffith-Benvenuti trilogy.

Emile Griffith and Nino Benvenuti became good friends during their trilogy, going through ring wars together will sometimes do that, it's a bond that's forged in fire, you can't really understand it unless you've been in a ring war.

One more series I want to talk about was the Emile Griffith-Carlos Monzon series, they fought twice but Griffith was past his prime. Yet despite being past his prime, he damn near took the middleweight title from Monzon. If you're not familiar with Carlos Monzon, he's one of the greatest middleweights in history, top three, right there with Hagler, Greb, Robinson, he ruled the middleweight division with an iron fist for seven years in the 1970s, making 14 defenses of his title. Carlos Monzon was from Argentina, but he was a violent bastard of a man, he was evil, he physically beat his girlfriends and even murdered his wife by throwing her off a balcony, she actually shot him before he threw her off the balcony but he survived the shooting. He was charged for her death, convicted, and sentenced to 11 years in prison. He died in a car crash in 1995 while on furlough from prison. Carlos Monzon was brilliant in the ring, he was tall and had a long reach, an iron chin, a phenomenal ring technician, but a real POS excuse of a man. Anyway, Emile Griffith made another bold as hell move by trying to take Monzon's crown, Griffith was past prime but he went for it anyway. Griffith was at a disadvantage against the taller and rangier Monzon, he made it to the 14th round in the first fight before being stopped, but Griffith was never one to give up, and he was great at making adjustments and winning rematches, so he took another crack at Monzon, and damn near took Monzon's crown but gassed out at the end. Despite losing the rematch, he took Monzon the distance, it was one of Griffith's greatest moments, a past prime, smaller, natural welterweight almost taking down one of the top three middleweights of all-time, not too shabby.

The great Carlos Monzón made his seventh defense of the middleweight championship with a tough 15 round unanimous decision in a rematch with former champ Emile Griffith at the Stade Louis II in Fontvieille, Monaco in 1973.

Griffith, former welterweight and middleweight champion, did well attacking Monzón in their first bout at Estadio Luna Park in Buenos Aires a few years earlier. But he had serious issues with Monzón's reach and style, as most did.

Monzón rattled off a few defenses after their first bout, including righting a wrong in a rematch with Bennie Briscoe. Griffith had clearly lost a step, but he'd gotten enough wins in the meanwhile to justify a rematch.

A ringside report said:

"Middleweight champion Carlos Monzon of Argentina struggled through 10 rounds, often outboxed and outpunched, but turned on a late spurt Saturday night to beat Emile Griffith and deprive him of a sixth world title.

Monzon, 31, staggered in the 8th round by a Griffith right, cut the 35 year old New Yorker in the 14th round, culminating the rush that saved his title. In the 8th round, when Griffith seemed to be leading on points, Monzon scored a good left-right combination but was staggered by a Griffith right hand when he sought to press the attack.

Griffith was unable to take advantage of the situation and two rounds later showed signs of tiredness for the first time. There were no knockdowns."

After the final bell, Monzón ignored Griffith, who tried to embrace or at least salute his opponent. The announcement of a decision to the champion was met with a mixed reaction from the crowd of about 10,000.

"It was the most difficult fight of my career," Monzón said. "I thought it was a draw up to the 11th. Griffith is very strong, but I won."

"It was a rough decision," Griffith said. "I really thought I became champion again."

Ok, let's get some great shots from Emile Griffith's career in here. Look at that masterful jab, right in the face of Benvenuti.

This image was actually used on his 2010 Ringside Boxing Round 1 trading card, very cool.

Griffith with Dave Charnley in England before their bout. Griffith was a globetrotter, I believe he fought in something like 13 different countries.

Griffith with his mom.

Griffith vs Luis Rodriguez.

Griffith with his legendary trainer Gil Clancy, one of the most dynamic duos in boxing history.

Great shot of Griffith and Benvenuti about to go into battle.

Griffith and his team after winning back the middleweight title.

Griffith and Jose Stable battle during a clinch, Griffith was a master at clinch warfare.

Griffith lands a right hand against the great Jose Napoles.

This is an interview conducted with Emile Griffith in 2001. I always love to read what the legends have to say about their careers, their battles, their opponents.

Interview: Emile Griffith

Ike Enwereuzor

Emile Griffith began his professional debut June 2, 1958 as he won a fourth round decision over Joe Parham. He was first introduced to amateur boxing by his uncle in St Thomas, West Indies when he was 18 years old. Six time champion Emile Griffith was inducted into the International Hall of fame in 1990 and world hall of fame.

IE: I'm here with 6 time champ..What are you doing these days?

EG: I've been busy training fighters and attending special events

IE: You're considered as one of the greatest middleweight of our time. What did you think of Hopkins-Trinidad fight, if you watch it?

EG: Yes, I watched the fight. Hopkins did well but I don't think I saw the same Trinidad I know. I think Trinidad fought good too but Hopkins was the better man that night. If they ever fight again I think Trinidad will get him this time. Maybe Trinidad underestimated Hopkins or he didn't train hard enough.

IE: Why did you decide to box?

EG: I wanted to play Baseball but I was small to play. Howard Albert asked if I ever boxed. He took me to the gym department parks on 28th Street, NY. After that, I would go over to the gym after work to workout with the guys and I get beat up but I stayed around to learn. I won the Golden Gloves in 1956 then turn pro in 1958.

IE: What do you remember from your pro debut?

EG: It's been a long time. It was at Old St Nicks in New York City and I beat the guy by decision.

IE: Your toughest professional fight?

EG:My toughest fight was with Dick Tiger. Nino was tough too and Carlos Monzon was too. I was lucky to beat Tiger. I always say I was lucky to win all my fight but I trained very hard for all of them. Kids today don't train as hard as we did those days. They want it easy but it can't work if you don't prepare very hard. This is what I teach my fighters.

IE: Where did you use to camp for your fights?

EG: We use to go Upstate New York, called Concord Hotel in Caskills. We took training very serious, I would be practizing moves, body punches, right hand and throwing left hooks. My trainer Gill Chancy was a good trainer and one of the best in the business.

IE: How would you compare the fight to your fights with Dick Tiger?

EG: Tiger was my good friend, we use to spar together at Gleason gym in Bronx, NY then. Few years later I got a chance to fight him, I guess that help me to beat him because I knew his style. I learn a lot from Tiger and learn from me too. When we sparred together I was like 147 and he was a full middleweight. We use to go to central park together to do our road walk too. My two fights with Dick Tiger was a heal of a fight. I think we had a tougher fight than Hopkins-Trinidad.

IE: Your thoughts on Tyson-Nelsen bout?

EG:Are you making jokes, Ike? Tyson fought a white guy who was strong but can't fight, Tyson should have stopped him earlier. He kept holding Tyson but Ref. Steve Smoger just kept breaking them up. Mike needs more work before he fights for any title.

IE: What else can you tell me about your meetings with Dick Tiger?

EG : I was like a boxer, he was a puncher and boy, Dick Tiger can hit. I was fast and my trainer Gill Chancy use to tell me not to let my opponent throw shots first at me, I should be the one throwing first. I was the better man that night.

IE: Which fight of your career was your highest payday?

EG: It was my fight with Nino Benvenuti. I made almost quarter of a million.

IE: Can you compare you fights with Nino Benvenuti

EG: We had three good fights. He was tough on all 3 fights, 2 in 1967 & third one in the garden took place in 1968 but I was a little tougher. I think I won all our fights but they gave me only the second one. One of the fight with him I slipped but they called it a knock down and we protected.

IE: How would you compare the old Madison Square Garden to the new?

EG: The old Garden was good but now we have something better and larger. Now, they have various major events there like Music, basketball, Hockey, Boxing and more.

IE: How did you feel to capture your first title against Benny Paret on April 1, 1961?

EG: It was a great fight for me and I was a happy man. I knocked him out in 13th round and I did a back flip in the ring after I won the title. I felt like I owned the whole world. It was definitely a great feeling to win the title. I received a lot of congratulations from my sparring partners, many fans, my baseball team (The Griffs) family & friends.

IE: Tell us about "The Griffs" ?

EG: It was a baseball team I formed to teach kids how to play. I started it after I turned professional in early 1960's.

IE: What was it like to be inducted into International Hall of Fame in 1990?

EG: It was fun. A lot of my friends, New York Commissioners were there. It was very exciting moment for me and my family.

IE: Your most memorable moment of your career would be...?

EG: My third fight with Benny Paret....... Oh my God, it was a disaster. I almost lost my career. Benny passed away, may his soul R.I.P after that fight, I didn't want to fight any more. My mind can't get me to fight. I was getting hate mails from Cubans calling me a murderer but I also got positive mails from fans who cared about me. The fans wrote to me saying it wasn't my fault, that was boxing. I even received a mail from a fan who's a truck driver he told me how a little boy ran in front of his truck and he couldn't save the kid's life. He said, that never made him to quit his job. It was an accident after receiving a lot of mail as such my trainer encouraged me to get back in the ring so I tried to go back. The advise and support from fans made me get back into it. They said, we love you and want to see you fight again champ. I didn't know I was much appreciated till then.

IE: Can you please describe your fights with Carlos Monzon?

EG: He was taller and had a longer reach than so it was hard to get into him but I do get in, I made him feel my punches.

IE: Tell us about your Fight with Hurricane Carter?

EG: They did a movie on him. I lost to him but it's time for Emile. I trained Wesley Snipes for a movie "Street of Gold" and I was show a little in that movie too. Wesley knows his stuff and I think he could play my role very well.

IE: Your favorite fighters during your era would be ....?

EG: I like "Sugar" Ray Robinson, I use to do road walks with him and I sparred with him one at Gleason Gym in the Bronx. Joe Louis, I met him few times in Las Vegas and New York. Archie Moore was a very good man, he showed me a lot in the gym too. One thing I liked about him was that he never show off.

IE: What's your impression of Jose Torres?

EG: Another friend, he was the captain of the Golden Gloves and we sparred a lot then. I learn a lot from him though we always tried to out run each other.

IE: Your advise to those who may be interested in becoming a boxer?

EG: Firstly, start with running, get in shape but they should leave me alone if they are not doing well in school. I was lucky to make it it's not going to be easy for anyone who decides to box. If they find someone who cares they must constantly listen to trainer and do what they ask you to do.

IE: Where are you training fighters?

EG: I've my gym at gleason gym and I go to other gyms too.

This is one of my favorite photos of Emile Griffith, I actually own this photo. He was always training hard, in phenomenal shape, living the life, boxing isn't just a sport, it's a way of life, and if you're not 150% dedicated and in shape, you won't last long in the hurt business.

One last photo of Griffith.

The great Emile Griffith, 1x junior middleweight, 3x welterweight, 2x middleweight = 6x world champion.

The defensive brilliance of Emile Griffith.

Wicked shot from Fabio Wardley-Joseph Parker this past Saturday.

Stranger than Fiction: Mexican Joe Rivers, who controversially lost a double-knockout title fight to Ad Wolgast in 1912, was rediscovered by a journalist in late-1950s Los Angeles living alone in a windowless room, his only possession a 200-year-old violin which he played daily.

During his career from 1910 to 1923 they called him Mexican Joe Rivers, "The Lethal Latin." A Californian phenom, he burned his way through the bantamweight and lightweight ranks and was part of the notorious double-knockdown bout with Ad Wolgast, "The Michigan Wildcat", in which both men went down simultaneously but Wolgast was helped up by the ref while Rivers was counted out. Rumors had Rivers dying in WW1 on the SS Tuscania but in 1955 a sportswriter for the LA Times named Frank Finch heard about a Joe Rivers who had been hospitalized and recalled the name.

Sure enough, it was Mexican Joe Rivers, living in a little room on West Second Street with no windows. He wasn't a Mexican, he explained, to the first man who ever listened. His name was Jose Ybarra and he was a 4th-generation Californian of Spanish/Native blood. Once upon a time a boxing promoter had asked him where he lived and he'd replied, "Down by the river" so he became Joe Rivers and then a Mexican because Mexicans came to fights.

He'd earned a quarter million dollars in the ring, had dozens of suits, a touring car with his initials on the side, bought his mother a nice home. All gone now. Kids like him in the fight game had no idea what to do when the money came in, and nine times out of ten the people around them who understood money were only there to take it away.

His only possession of any value was his father's 200 year-old violin. He played it every day.

“I guess I had a million friends,” he said. "Gone now, most of them. The others - they don’t come around much anymore.”

Joe Louis made the 16th successful defense of his world heavyweight title with a ninth-round stoppage of Blue island, Illinois' Tony Musto in Saint Louis, Missouri in 1941. Musto was still on his feet and still willing to fight when referee Arthur Mercante had seen enough after a methodical beating by the champion. Never before knocked down in thirty-nine fights, Musto found himself on the canvas in the third round. But the sturdy challenger bounced up and proceeded to present stubborn opposition to Louis. Musto's right eye required stitches when the fight was over.

35 years ago, 73-year old Billy Conn, "The Pittsburgh Kid", walked into a convenience store for some coffee only to find it being robbed by 27-year old Nick Conyer.

Conn rushed the robber and in his words, “fixed him” with his favorite punch, a left hook. What a legend.

Maciej Sulecki wasn’t exactly enjoying all the punches to the head that Diego Pacheco was dishing out at him in August 2024, but he could take them. Across 14 years and 35 fights as a pro, the Polish super middleweight had acquired all the veteran savvy needed to roll with shots, buy time when buzzed, use his legs and get through every sticky situation he had ever been in. But when Pacheco put the full torque of his 6-foot-4 frame into a whipsaw left hand that landed just under the right elbow 41 seconds into the sixth round, there was nothing Sulecki could do. Veteran wiles didn’t count for much. Steely resolve didn’t do him any good. His body spun around 270 degrees clockwise as it crumpled. Sulecki went into the fetal position. Then he rolled onto his back, and he couldn’t lift any part of himself off the canvas before referee Ray Corona counted 10. Body-shot knockouts aren’t usually as eye-popping as a crack to the jaw that renders a fighter unconscious, a reality reflected in the fact that only once in the 35 years that “The Ring” magazine has been naming a Knockout of the Year has that honor gone to a pure body-shot KO. But body-shot knockouts are beautiful in their own way. There’s an accompanying agony on the face of the victim that we don’t get with head shots. And there’s a cerebral appeal to a boxer going downstairs to end matters when faced with a stubborn opponent who can take everything being dished out above the neck – as Sulecki, who had never been stopped before, did for a little over five rounds.