Longacre and his connection to Chile [Updated with discovery!]

Boosibri

Posts: 12,502 ✭✭✭✭✭

Boosibri

Posts: 12,502 ✭✭✭✭✭

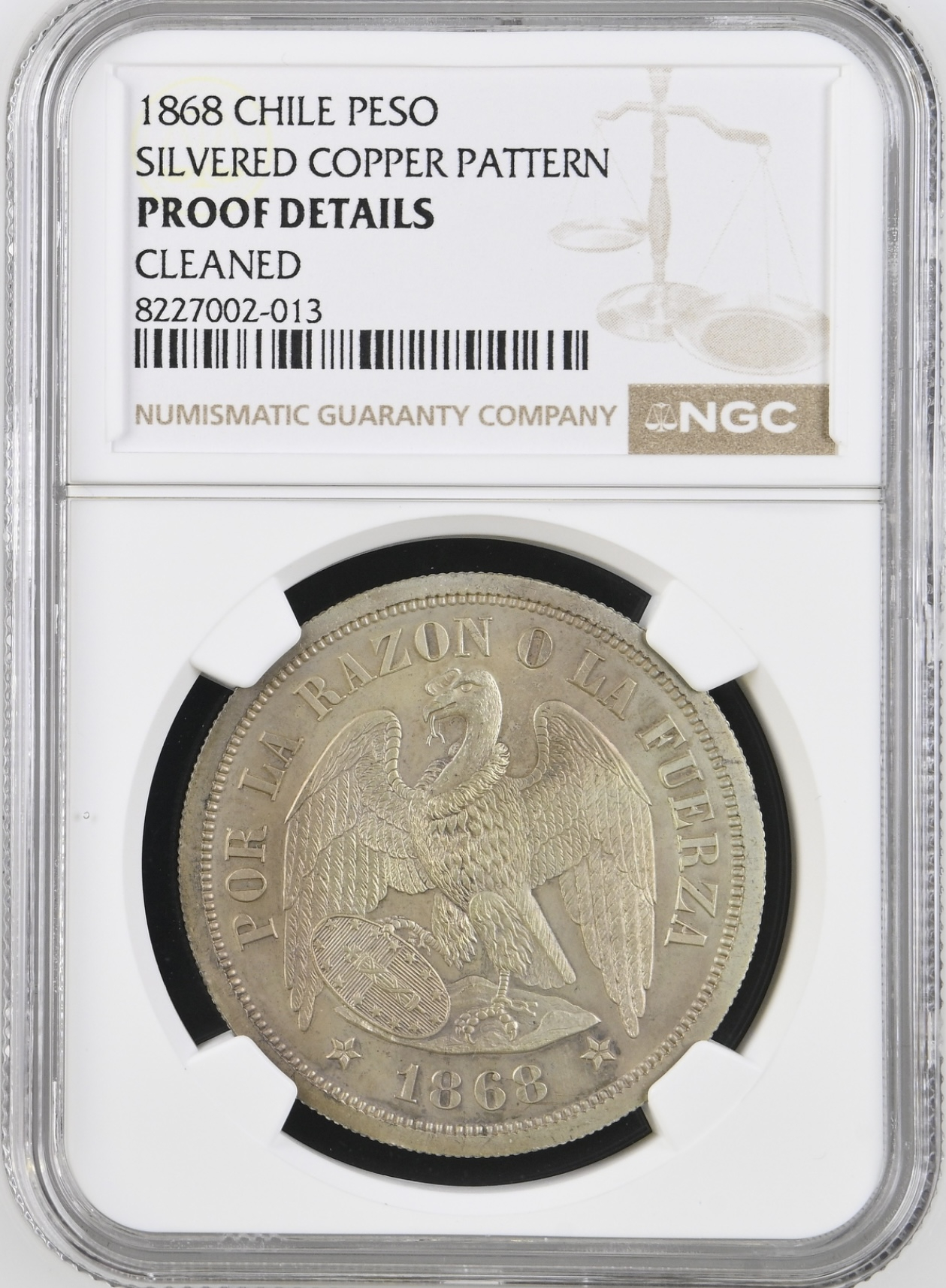

Since acquiring this 1868 Chile silver proof peso, one of two known (shown below), at the Pittsburgh ANA, I have been researching the coin and searching for a potential provenance. The other coin ironically sold at the ANA sale, a brushed details coin which was once a part of a full set whos provenance currently starts with King Farouk.

One stream to explore is the connection between Longacre and the Chilean mint at the time of this pieces manufacture. RW Julian overviews the relationship extensively below, but to summarize, Longacre agreed to furnish the dies for the new Chilean coinage to the government of Chile with Paquet completing the design. The working theory then is that this is a presentation piece, likely give to Longacre, stemming from his work and involvement in the start of this line of coinage.

I have no way of proving that, but that is the hypothesis and the work to continue.

Here is the estate sale for Longacre which contained foreign medals but no coins. https://nnp.wustl.edu/library/auctionlots?AucCoId=511814&AuctionId=515574

Longacre and the Chilean Dies of 1867

By R.W. Julian

Collectors who specialize in the coins of Chile have long known that there was a dramatic change in the dies for the gold and silver coinage beginning in 1867. It is little known, however, that the dies were executed in the United States under the personal direction of James B. Longacre, chief engraver of the United States Mint at Philadelphia.

Chile tried to obtain independence from Spain as early as 1810, but within three years the rebellion had been crushed and it was not until 1817 that a successful revolt was mounted by Bernardo O’Higgins.

The Santiago Mint had long been well known in Spanish America for its coinage, though never produced in large amounts. The area could have easily have been served by the mints at Lima or Potosi, but regional pride demanded a mint and got one in the early 1740s.

There are several vignettes found on the early Chilean coinage, but two of them have remained current until the present day while a third was used until the 1890s. The first was the national coat of arms adopted in June 1834 and which featured a condor to the right and huemul (a species of native deer) on the left surrounding a five-pointed star. Each animal bears a naval crown while surmounting the whole is a three-feathered plume. The full coat of arms first appeared in 1836 on the eight escudos gold coin.

The condor was to appear on the eight reales piece in 1837, closely followed by other silver denominations. The condor normally was shown with its feet breaking the chains of Spanish tyranny.

The third major staple of Chilean coinage was the female figure representing the Republic. Her right hand rests on the 1833 Constitution and sustains it by this action. The personification of the Republic was to disappear from the coinage in 1892.

By laws of January 9 and March 19, 1851, the National Congress decreed that the country would change to a decimal system of coinage, abolishing the old Spanish denominations of reales and escudos. The first decimal gold appeared during the same year, but apparently the first decimal silver was not coined until sometime in 1852. A few rare Medio Decimos (five centavos) are known with the 1851 date, however.

The Santiago Mint began the new coinage during 1851 and 1852 but within a few years there arose dissatisfaction over the poor workmanship of the dies. New designs were produced for the silver 50 centavos (half peso) in 1862, as well as smaller denominations by 1865, but most were judged a failure by the public at large. The principal change was to put the condor in a sitting rather than flying position.

By 1865 quality of the coinage was an open topic of discussion and the government finally decided that something had to be done. Coins from various nations were examined and those of the United States found to be of the best quality. There was also a natural dislike of European monarchial coins and it was felt that U.S. engravers would understand the Chilean emblems much better as both countries had thrown off European domination.

In early 1866 the Minister of the Treasury in Santiago instructed the Chilean Chargé d’Affaires in Washington to sound out the Americans about preparing improved coinage dies. Chargé Buraga called upon the U.S. State Department and requested permission to deal directly with the Treasury, which was granted.

Buraga obtained an appointment with Treasury Secretary Hugh McCulloch; he then asked the Secretary’s advice on how to proceed with his orders from Santiago. McCulloch suggested that Buraga visit Philadelphia to see Chief Engraver James B. Longacre, whom the Secretary felt would be able to provide all the necessary answers. In early March 1866 Buraga went to Philadelphia.

numnewus201215_article_032_01_06

The Chargé spent several hours with Longacre and was able to examine firsthand the quality of the Philadelphia dies. Buraga and Longacre agreed tentatively on a price for the work (which was to involve dies and hubs for 9 different denominations, four gold and five silver) but the chief engraver informed him that Treasury approval would have to be obtained. On that understanding Buraga returned to Washington.

(Longacre was being careful in his dealings with the Chargé because there had been an incident in the mid–1850s which left Longacre holding the financial bag. He had contracted with the Navy Department to engrave dies for the Ingraham medal voted by Congress for the rescue of an American in the Levant. Longacre was paid $2200, but an enemy in the Mint tipped off the Treasury about the payment and it was discovered that an obscure law forbid payments of this type to government employees. Longacre had to return the money.)

The next step was to apply formally for Treasury Department permission and then work could begin. The Treasury, as a matter of course, asked Mint Director James Pollock in Philadelphia for his views. Longacre had not informed Pollock of the arrangement but did not think it necessary because of McCulloch’s involvement.

Pollock took offense at the whole matter and rather pointedly informed the Treasury that it “would not be expedient” for the chief engraver to use Mint equipment or even, for that matter, to do the work at all. Pollock then suggested that another engraver be employed and that he (Pollock) and Longacre jointly superintend the engraving.

McCulloch, even though surprised at the answer, acquiesced and informed Buraga of the new arrangements. This was unexpected and Buraga wrote Santiago to ask for further instructions because of the complications. The Chilean Treasury, in a reply received in Washington during early June 1866, ordered Buraga to make the best arrangements possible.

numnewus201215_article_032_01_07numnewus201215_article_032_01_08

Buraga now wrote Longacre apprising him of the situation and asking his advice on how to proceed. The chief engraver was less than pleased to discover what Pollock had done (there still had been no consultation of any kind at Philadelphia) and wrote the Chargé that Pollock was not qualified to superintend anything of the sort as he did not have the technical background.

Longacre also wrote Buraga that it would be necessary to make out a fresh estimate of costs now that mint equipment could not be used. Longacre indicated that there was only one artist capable of doing the work under the new ground rules and that this man was tied up on another project for the time being. The chief engraver believed, however, that this as yet unnamed engraver could be persuaded to do the work under Longacre’s direction.

Although the March 1866 estimate is not available, the June one called for a payment of $10,000 in current funds (greenbacks) for nine sets of dies and hubs. $1,000 of this amount was budgeted for the necessary detailed drawings. Dies and hubs for each of the denominations would cost $1,000.

Payment was to be made at stated intervals, as the sets of dies and hubs were finished. Longacre also stipulated that letter and figure punches were to cost $1 each. It was requested by Longacre that he have some leeway in interpreting designs if improvements were found necessary for a proper work.

Although the engraving would have to be done outside the Mint, Longacre guaranteed that the finished work would equal that currently being done for the United States. The prospective engraver, Anthony C. Paquet, had formerly been an assistant engraver at the Mint, leaving to go on his own in 1864. Paquet worked directly in steel, a very difficult and demanding way of preparing dies.

Paquet is known to have done dies for several Latin American countries, including Peru in 1863 and Bolivia at a later date. He also contributed a pattern Trade Dollar to the U.S. coin series. His medals are generally of a very high quality; several were done for those awarded in gold by Congress.

Uncertain once more, Buraga again wrote his superiors for instructions. The answer came back that the proposal had been accepted and to proceed with the formal contract. The latter, which has not been seen, was signed by Buraga and Longacre about August 21, 1866, and the conditions followed the June proposals.

One reason that there was no major problem in signing the August contract was the political atmosphere of the times. Mint Director James Pollock was upset over the Reconstruction policy towards the South pursued by President Andrew Johnson. In mid-September his irritation reached the boiling point and, in a fiery letter to the Chief Executive, he resigned the post. His successor was William Millward, who left Longacre to his own devices.

On September 3 Longacre and Paquet signed their contract, which required the latter to execute the Chilean dies in the best style and as quickly as possible. Just how the work was apportioned between the two engravers is not clear, but Paquet received only $500 per denomination for his work and Longacre the other half. Paquet arranged for the detailed drawings and received a commission for this.

Buraga had furnished a detailed description of the coinage as well as samples of all coins in current use except the Peso which, for some unknown reason, was not forwarded from Santiago. These coins were turned over to Paquet, who receipted for them on September 4.

Paquet had other work to do and did not commence the Chilean dies for several weeks. In the meantime an unidentified artist prepared the drawings which Paquet would use in his work.

The engraver seems to have begun with the Half Peso (50 centavo) piece. The instructions for these dies included a strengthening of the rock upon which the condor stood as well as stronger feathers on the breast of the bird. According to Santiago officials, the feathers on the current coinage wore down much too quickly in circulation. On the shield being grasped by the condor the artist was to put 15 stars instead of the 14 then appearing in order to represent correctly the number of provinces.

For the reverse of the 50 centavos Paquet was instructed to prepare a smaller laurel wreath as the present one was much too crowded. It came too near the plumage at the top and gave the coin a poor appearance. Instructions for the other silver coins were much the same as for this piece.

By late January 1867 Paquet had finished the hubs for the 50 centavos and the Veinte (20) centavos. Working dies were prepared from the hubs and copper proofs were struck under Longacre’s direction (probably in the Mint as Pollock was no longer there) and forwarded to Buraga. The copper patterns were then sent to Santiago for a careful examination. The Chilean authorities, including President Perez, were very pleased with these first samples.

In early February 1867 Buraga was replaced as Chargé d’Affaires by Alberto Blest Gana, who proved as capable as his predecessor. On February 26 Longacre notified the Legation that another set of dies, for the Peso and Decimo (10 centavos), was completed and the copper proofs nearly ready.

Longacre had intended to deliver the fresh set of copper proofs in person, but a sudden and severe illness prevented him from doing so. Instead he sent his son, James M. Longacre, to meet with Gana and receive payment for the latest work. In March Paquet then received $1000 for the silver Peso and Decimo dies.

On April 17 Longacre notified the Legation that the gold Peso and Escudo (2 pesos) dies had been finished. It was noted, however, that there had been an accident involving the working dies for the Escudo and another die had to be made before the copper proofs could be made and sent on for inspection. It was thought that the two remaining gold denominations, the Doblon (5 pesos) and Condor (10 pesos) would be completed the following month.

The design improvements on the gold were similar to those ordered for the silver except for the figure of the Republic. The instructions noted that the “attitude” of the figure was good but, where her right hand touched the Constitution, improvement was required. In addition the word “Constitution” on the coins was split into three parts and very careful instructions were made for strengthening this lettering. Three separate punches had to be made for putting this onto the working dies. For political purposes it was necessary that the word stand out on the coins.

Longacre was able to report the last of the gold dies, for the Condor and Doblon, finished by June 17, 1867. The final payments were made shortly thereafter and Paquet also paid the last of the monies due him. In addition to the 9 sets of dies and hubs (36 pieces in all), there had been made 201 figure and letter punches intended for the working dies when being prepared in Santiago. Even the special monogram mintmark for Santiago was prepared by Paquet.

The entire shipment was carefully packed by Longacre and sent off to Washington in early July 1867. Longacre and Paquet were done with their part of the bargain and had performed their work very well. Gana then shipped the crate, which had been strongly ringed with iron hoops, to Santiago for the use of the Mint. Coinage with the new dies began almost immediately.

The Longacre/Paquet master hubs were employed for many years by the Santiago Mint although the last of the gold coins using these revised designs was struck in 1892. The gold Peso was rarely struck anyway while the Escudo and Doblon were not all that popular in commerce. For gold, only the Condor continued to be struck at Santiago after 1875.

Better use was made of the silver dies though they, too, last appeared in the 1890s. The final use appears to have been in 1891 for the 20 centavos and Peso although the 1926 restriking of the Peso (dated 1883) may have used the original 1867 hubs.

Changing economic times in Chile forced the government to abandon the high-quality silver and gold coinage of the nineteenth century for a long series of debased coins. It was the end of an interesting era in dies and coinage. ■

Comments

Fascinating context! The nascent Republican period in South America is full of numismatic treasures that don't have much documentation, at least not much that is well-known.

Great post!

I have had this Chile 50 Centavos 1870 since I bought it for 75 cents in the 1960's.

I knew nothing about the unusual US history of this coin until I read the above article.

Chile 50 Centavos 1870

Silver, 30 mm, 12.46 gm

This coin appears to have an overdate.

The Mysterious Egyptian Magic Coin

Coins in Movies

Coins on Television

One question that I think is now clear is that the So mint mark on the coin is legitimate and that it was not in fact minted in Paris, London or Birmingham which stands in contrast to most of the other Republican proofs for the era.

Latin American Collection

I thought this was going to be about forum member Longacre

excellent post-

Experience the World through Numismatics...it's more than you can imagine.

Well, after thinking that I struck out on the Longacre sale, I found out that there was a single loose page added in for sale after lot 250 containing 33 lots of Chilean copper and silver proofs! These seem to be the source of all Chilean proofs from 1867 to 1868. So, this coin is almost certainly ex. Longacre.

Latin American Collection

Great detective work on this. Hopefully enough to get the provenance put on the label but I’d think you’d have to show them that the coins in this auction were the only ones minted. Are there mintage records for the presentation prices that were struck?

No records of these being struck. It’s possible others were made of course but for example there were two 50c, and there have only been 2 ever documented. Same for the peso.

Latin American Collection

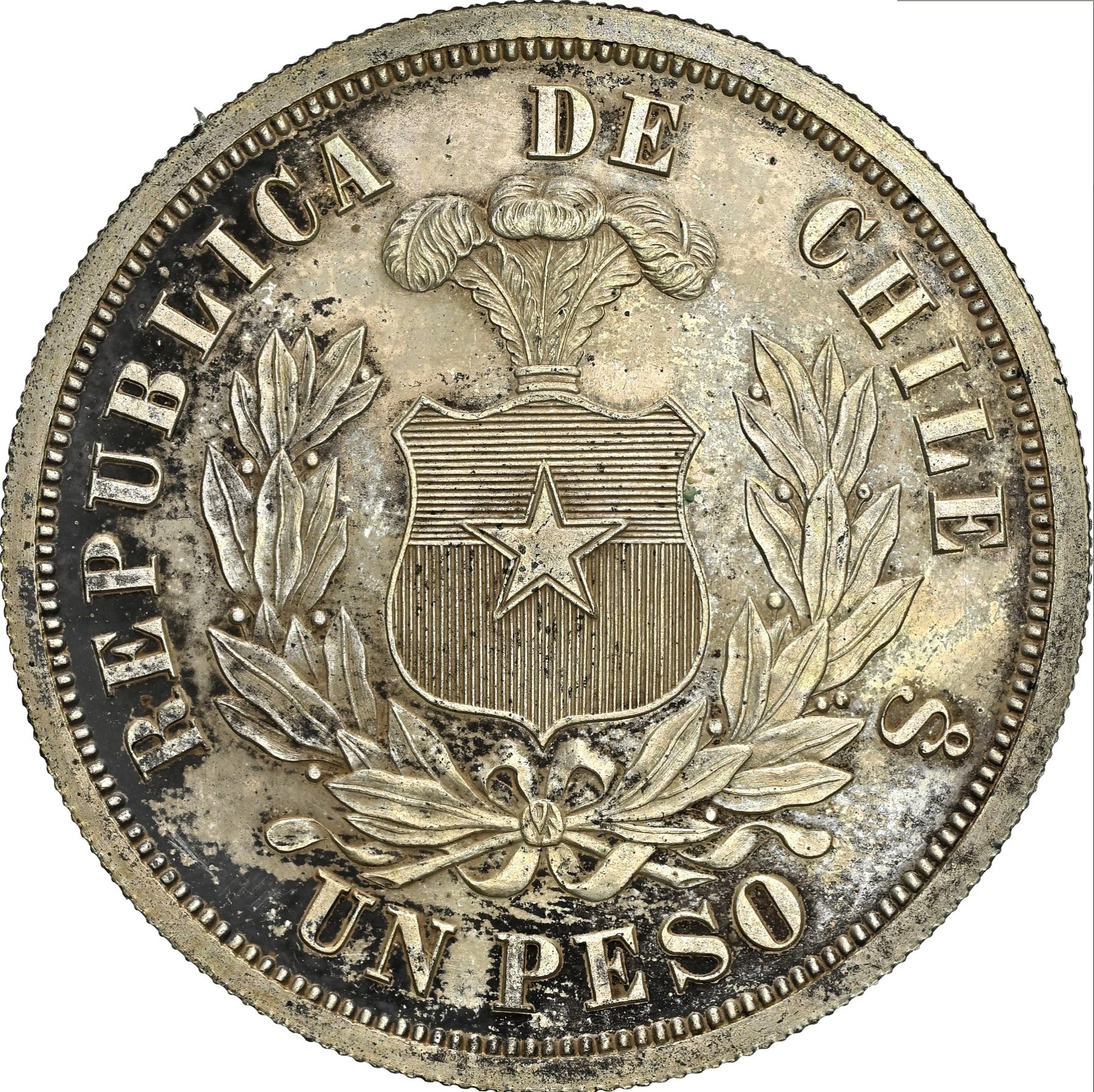

Here is the Farouk/Pittman coin in case anyone is interested.

Latin American Collection

Sold for $6000 (+20%). Someone got a huge bargain!

Well that worked

Latin American Collection

Congrats! Great detective work.

Before this thread, that’s the last name I would’ve expected to see as provenance to a Chilean Peso proof.

Found this from Mark Teller post Millennia. Wonder who the “Wonder Coin” dealer was.

Latin American Collection

It's a long shot, but perhaps its the user @wondercoin here on the US forum? https://forums.collectors.com/profile/wondercoin

Well hot-dang! You just win at everything don’t you?!

I'm BACK!!! Used to be Billet7 on the old forum.

Heritage listed a silvered copper proof, which I have never heard of. Doubtful that Longacre would have silvered a copper example, so perhaps a later concoction?

Latin American Collection

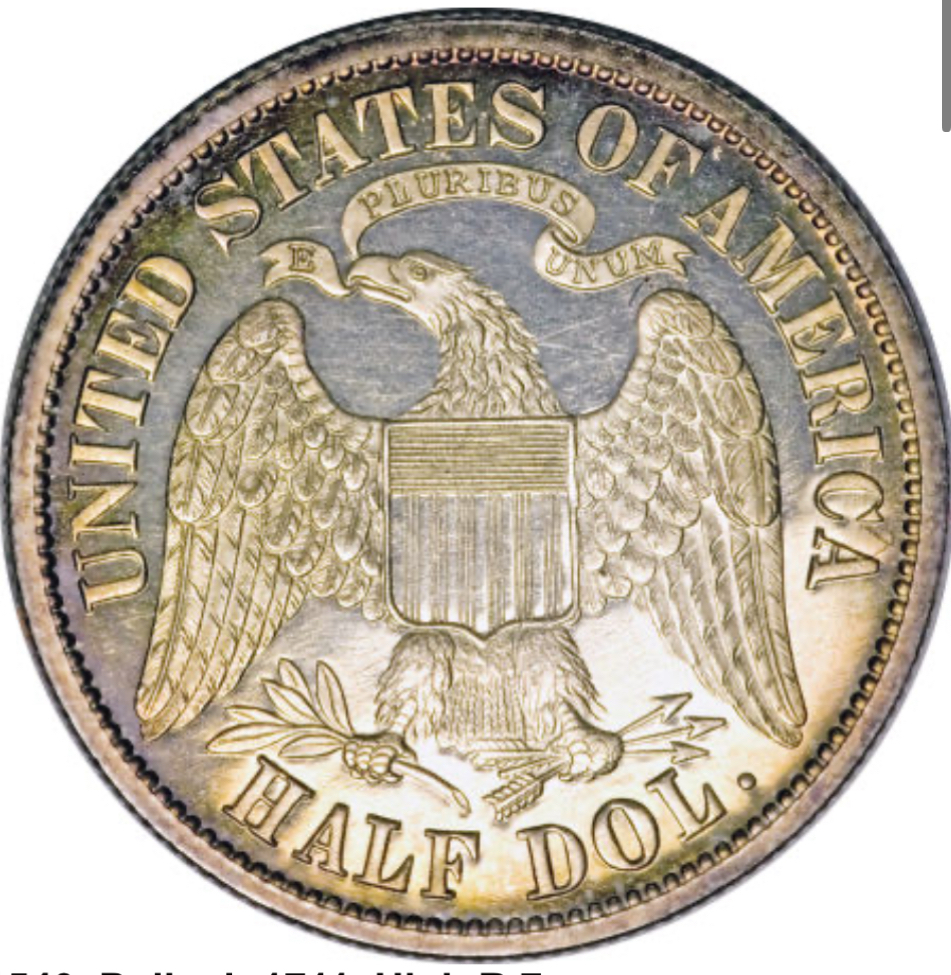

Here are a couple of pattern reverses for U.S. half dollars by Paquet, from 1859 and 1877. His style is very recognizable.

Doggedly collecting coins of the Central American Republic.

Visit the Society of US Pattern Collectors at USPatterns.com.

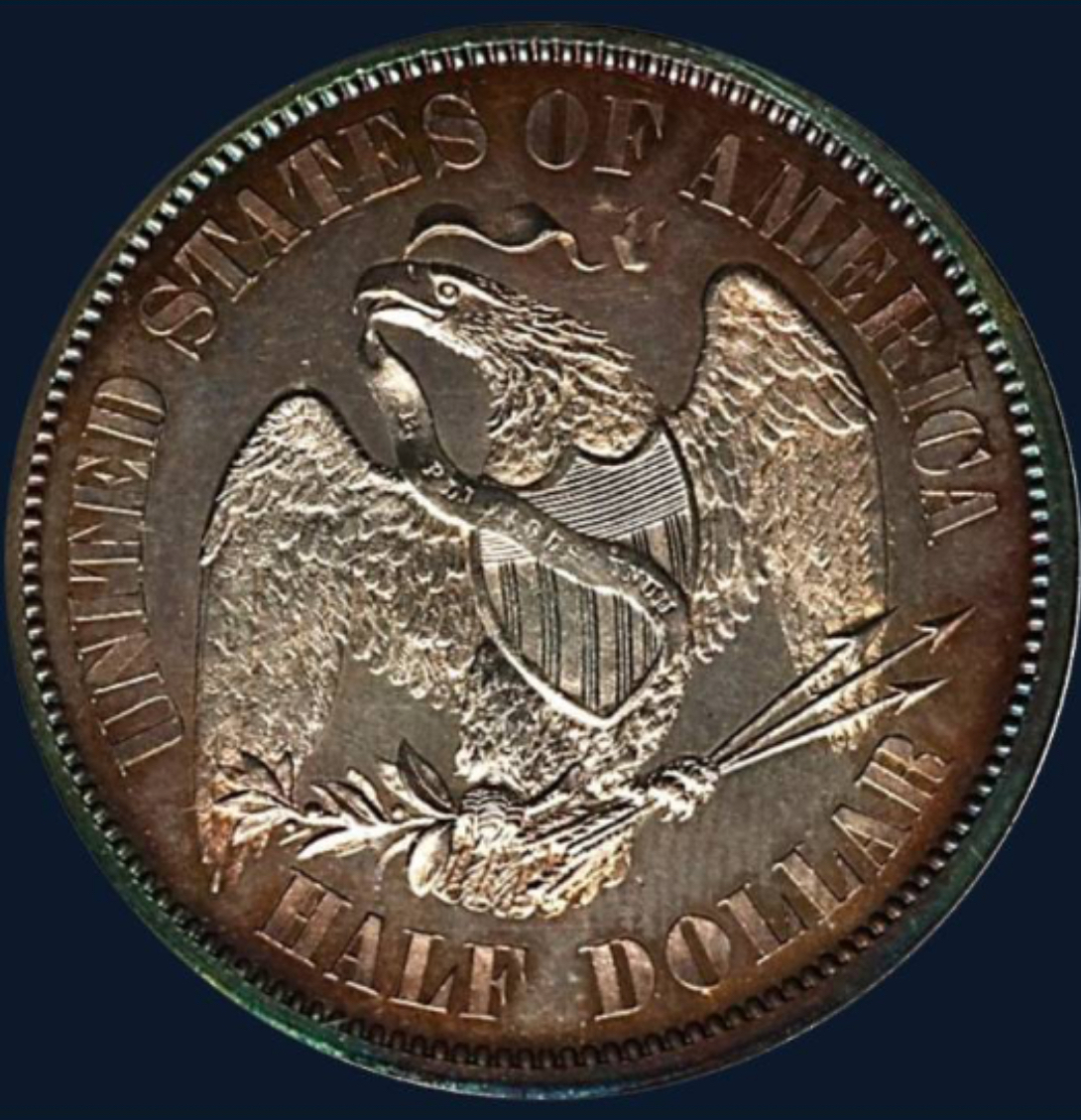

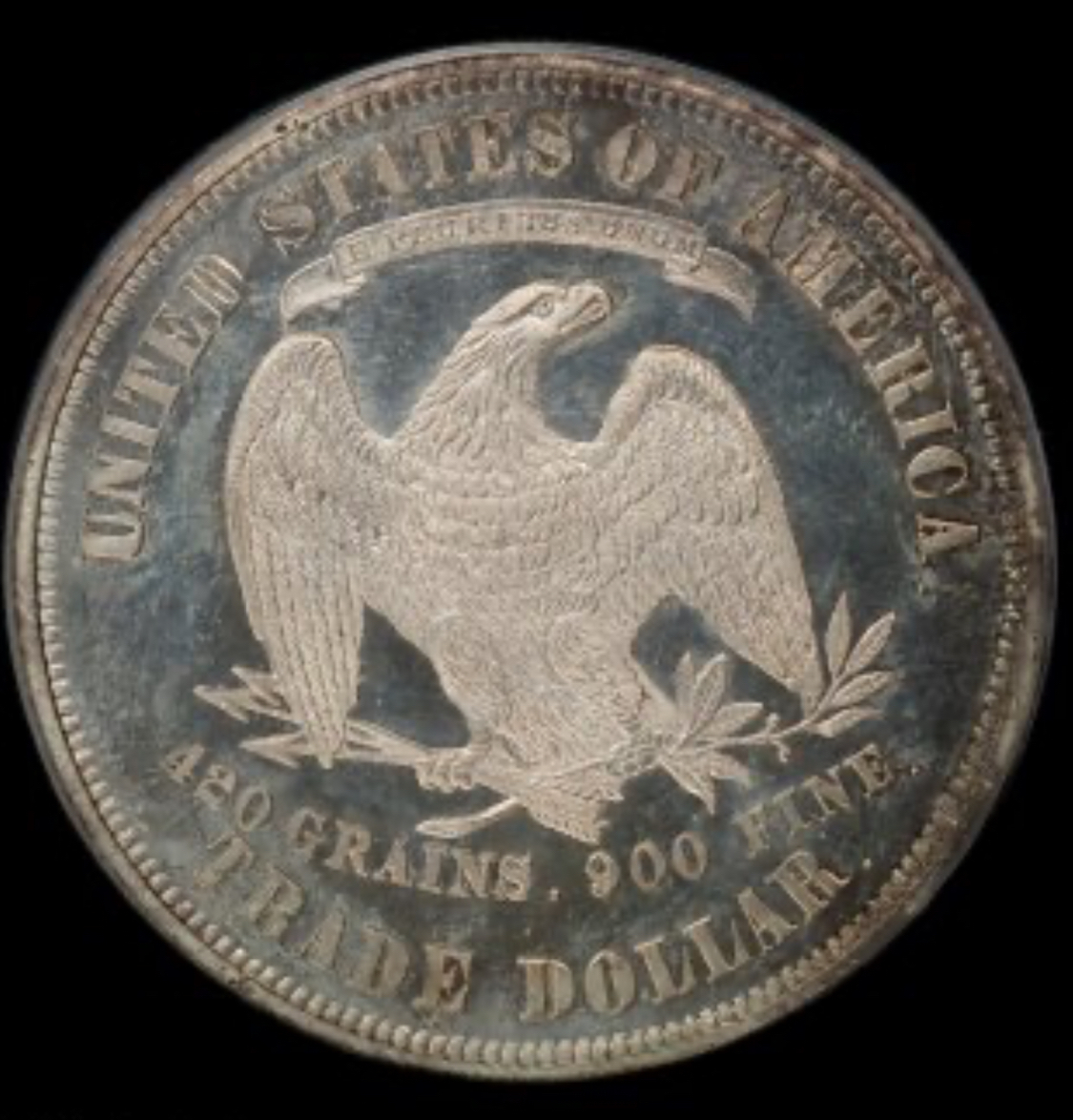

And while we’re at it, a Trade Dollar reverse by Paquet.

Doggedly collecting coins of the Central American Republic.

Visit the Society of US Pattern Collectors at USPatterns.com.

dang it, read it all again 2 years later and thought exactly the same thing - did Longacre rocking the smoking jacket, dishing about frothy frenzies and well managed promotions do something interesting in Chile?

cool