Muhammad Ali famously said of the "Thrilla in Manila," "It was like death. Closest thing to dying that I know of". He also later reflected on the brutal fight by stating, "We went to Manila as champions, Joe and me, and we came back as old men".

Up next, "Mi Vida Loca" Johnny Tapia, 1990s and 2000s three-division champion from Albuquerque, New Mexico whose nickname meant "My Crazy Life."

Johnny Tapia, a man whose life was as wild and unpredictable as his boxing career was legendary. Born into unimaginable tragedy in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Johnny’s life seemed destined for hardship from the start. His father was reportedly murdered before he was even born, and at just eight years old, his mother was kidnapped, brutally attacked, and murdered—a trauma that left an indelible scar on his young soul. Raised by his grandmother, Johnny found solace in the boxing ring at the tender age of nine, channeling his pain and anger into a sport that would define his turbulent journey. Known to the world as "Mi Vida Loca"—a nickname tattooed on his body and a reflection of his chaotic life—Tapia’s rise in boxing was as thrilling as it was improbable.

As an amateur, he was a standout, winning multiple Golden Gloves titles. By 1988, he turned professional and began a career that saw him crowned as a five-time world champion across three weight divisions, holding titles in the super flyweight, bantamweight, and featherweight classes. But Tapia’s triumphs in the ring were constantly overshadowed by personal demons. Early in his career, he was banned for over three years after testing positive for cocaine, and his battles with addiction would haunt him for the rest of his life. Despite these setbacks, he returned with unmatched vigor, capturing the WBO super flyweight title in 1994 and thrilling fans with his unique blend of aggression, skill, and heart.

His rivalry with fellow Albuquerque boxer Danny Romero became one of the sport’s most heated showdowns, culminating in a unification bout in 1997 that Tapia won by unanimous decision, cementing his place as a local hero and an international star. The following year, he moved up to bantamweight, capturing another world title. However, his undefeated streak came to an end in 1999, in a Fight of the Year clash against Paulie Ayala—a loss that devastated Tapia and led to a harrowing suicide attempt. Yet, true to his nature, he bounced back, reclaiming a title in 2000 and continuing to defy the odds.

As Tapia moved up to featherweight, he became a three-division world champion, achieving a lifelong dream despite the turmoil in his personal life. Outside the ring, his story took more twists and turns. From battles with drug addiction and brushes with death to revelations that the man he believed was his father might not have been, Tapia’s life seemed to unfold like a Hollywood drama. Despite his struggles, Tapia maintained an incredible connection with his fans, who admired his fighting spirit both in and out of the ring.

Even in retirement, Tapia’s life was anything but quiet. He survived multiple overdoses, legal troubles, and devastating personal losses, including the deaths of close family members in a tragic car accident. Yet, he continued to fight, not just for himself but for the legacy he hoped to leave behind. His untimely death in 2012 at just 45 years old was a heartbreaking end to a life that had seen so much triumph and tragedy. In 2017, Tapia was posthumously inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, a fitting recognition for a man who fought every day of his life, both inside and outside the ring.

Johnny Tapia’s story is not just about boxing; it’s about resilience, the fight against the odds, and the unbreakable spirit of a man who refused to be defeated. His "Crazy Life" remains an inspiration to fans and fighters alike, a testament to the human capacity for perseverance even in the face of kindness.

Gosh, how do you even begin to talk about Johnny Tapia, he was an absolute legend in boxing. He was electrifying, intense, crazy, balls to the wall, he brought it all, and a gladiator in every sense of the word. The legendary boxing trainer Freddie Roach said Johnny Tapia and James Toney were the two greatest talents he ever trained. Tapia was seriously well-schooled in the ring with great physical assets: reflexes, speed, chin, recuperation, and stamina. He was on the downside, with 48 fights in and a heavy drug habit before he finally lost. He is one of the greatest body punchers in the history of the sport, he would just rip nasty shots to your body, with everything he had, it was beyond your normal body punching, almost like he was trying to cave your ribs in.

Tapia was involved in so many great wars in the ring, but my favorite would probably have to be his first fight with Paulie Ayala, two tough as nails warriors going to war in the trenches, it was a prototypical fight in a phone booth, a great back and forth battle with neither guy giving an inch. Tapia came up just short in this fight, it would be the first loss of his legendary career, but it really showed what an intense fighter and warrior he was. This was named fight of the year in 1999.

Johnny Tapia's best performance in my opinion was his fight with Danny Romero Jr, the fight was billed "the battle for Albuquerque" because both Tapia and Romero were from Albuquerque New Mexico, and it's one of the greatest boxing stories ever told because of the history between the two. Danny Romero was a monster puncher, nicknamed "Kid Dynamite", some of his knockouts were genuinely frightening, he had an overhand right that was absolute murder if it landed. Tapia and Romero had grown up together in Albuquerque, they first met at a gym when Tapia was 14 and Romero was 7. Romero's father had actually trained and worked with Tapia before they parted ways, so they all knew eachother closely. Romero Sr would go on to train his son Danny and develop him into a great fighter, by 1997 Danny was 23 years old and had a record of 30-1 and he was the IBF super flyweight champion. Danny was thought of as a young up-and-coming superstar, and had developed quite a fanbase in Albuquerque. Meanwhile Johnny Tapia was already a Superstar, he was 30 years old and was the WBO super flyweight champion and had a record of 41-0 and had his own fanbase in Albuquerque, so naturally there was some competition as to who was going to be Albuquerque's top dog so to speak. Danny Romero and Johnny Tapia were in a collision course that could only be settled in the ring, and the fact that this fight would be a unification bout just added to the drama. As the fight drew closer, both fighters began to hurl insults at eachother, it became personal, and their fanbases were also fighting, Albuquerque was basically divided into two camps that were constantly at eachother's throats, you were either pro-Tapia, or pro-Romero. The fighting between fans go so bad that the promoters of the fight had trouble trying to find a venue to host the bout, nobody wanted to host it out of fear of rioting between the fans. This fight really had it all, a personal feud between two guys that grew up together, unification of titles, the loyal fanbases that neither fighter wanted to disappoint, and of course the battle to be Albuquerque's top dog. It's a crazy story, all the drama surrounding the fight. This is what Johnny Tapia's wife Teresa had to say about the weeks leading up to the fight:

Tapia’s wife and manager Teresa remembers the fight and the training camp leading up to the showdown. It was the camp that terrified her and kept her up at night:

“You want to talk about being scared, that would be an understatement,” said Teresa. “He trained three and a half weeks for that fight.

Johnny was in a mess. Here I am his manager and his wife and I am watching footage of Danny training hard. He has all these special people. He’s in the mountains. Johnny’s in jail. We have no trainer. That was the kind of things leading up to this fight.”

Teresa’s concern for the fight only grew as the date got closer. “I was so worried I wanted to cancel the fight. I was already trying to get him to pull out. You know Johnny, he refused. He use to always say I refuse to lose.” The late great Eddie Futch came in to train Tapia. Jesse Reed also came aboard to handle mitts.

This is a write up from a man that was at the Tapia-Romero fight and remembers the whole thing very well.

Johnny Tapia versus Danny Romero — What a Night!

By: Ivan G. Goldman

One of my favorite boxing stories grew out of the storied July 18, 1997 clash between Albuquerque natives Johnny Tapia and Danny Romero at the basketball stadium of the University of Nevada Las Vegas campus.

The fight had percolated for years as both men stormed through opponent after opponent. There was no specific belt designated for Albuquerque’s favorite fighter, but you wouldn’t guess that from talking to Tapia or Romero. Tapia seemed to think it wasn’t fair for Romero to go around winning fights and fans while Tapia had to suffer a four-year banishment from the sport for his cocaine abuse. (He’d resumed his career three years earlier) And Romero looked upon Tapia as a has-been coke fiend who ought to slink back to the gutter where he belonged.

There was so much bad blood between the two camps and their respective fans that the promoters had trouble finding a venue willing to take their money. After the University of New Mexico refused to even consider it, lead promoter Bob Arum of Top Rank made a deal with the Las Vegas Hilton. But the hotel execs were always skittish about hosting thousands of die-hard fight fans from Billy the Kid territory. News media hinted that such a crowd could be uncontrollable, like Visigoths sacking a city.

Then in the third round of their June 28 rematch, Mike Tyson bit off a piece of Evander Holyfield’s ear at the MGM Grand. It sparked such a violent riot that the casino ejected paying customers and closed down gaming tables for hours. It’s hard to imagine anything more sacred in Vegas than the principle of round-the-clock gambling. To gaming executives, calling a recess was like being forced to throw their mothers out the back of a speeding pickup truck.

The Las Vegas Hilton panicked, and less than a month before the fight, annulled the contract, claiming the promoters hadn’t fulfilled some obscure insurance clause. Arum, whose relationships with Latino communities was a bedrock of his promotional business, didn’t need a scorecard to know who to side with. He insulted the hell out of the Hilton. “This is an insult to the Hispanic people,” he said, encouraging a boycott against the casino. After the big bad casino turned chicken it was cast out of the fight community. No promoter would ever trust it to keep its word again, and the divorce was final. Arum scrambled and came up with UNLV. The fight was still on.

Super flyweights Romero and Tapia were like a rock and a hard place. This would be like Leonard-Hearns, a mystery that everyone wanted to see solved in the ring. Tapia, a graceful boxer with a killer instinct, was up against a younger man who hit so hard he reminded fight guys of Roberto Duran. His punches sounded like hammers pulverizing human flesh.

Sitting next to me that night was Ramiro Gonzalez, now a publicist for Golden Boy Promotions. Then he was the boxing writer for La Opinion. Gonzalez had $50 riding on Romero. But a couple rounds into the great, give-and-take fight, Gonzalez, as excited as everybody else, started yelling things like, “Go underneath, Johnny. Step over and throw your right.”

Ramiro, I said, what the hell are you doing? You bet on the other guy! “I know,” he screamed waving his fist in triumph, “but Johnny’s boxing so beautifully I can’t help myself.” That was a true fan, what boxing is all about. I’ll never forget it.

After one of the early rounds Johnny leaned over to the media section and announced, “He doesn’t hit so hard.” Actually, Romero did hit amazingly hard, just not hard enough to worry Johnny. His life had been so difficult that to him, taking punches was a walk in the park. He fought like a magician in there, making sweet, unpredictable moves to hit and not be hit, the way it’s supposed to be done.

FIGHTHYPE FLASHBACK: THE BATTLE FOR ALBUQUERQUE...JOHNNY TAPIA VS. DANNY ROMERO

By Brad Cooper

With a verbal assault from Rock Newman, manager of former heavyweight champion Riddick Bowe, and a crack to the back of Andrew Golota's head delivered by Jason Harris, a cell phone wielding member of the Bowe entourage/management team, a riot ensued, both inside the ring and out, that would soon spread throughout the Mecca of Boxing and result in numerous arrests, including Harris himself.

The scene at Bowe-Golota I is well-known to boxing fans and general sports fans alike, linked forever to the image of Golota, affectionately known as the Foul Pole, crippling Bowe with repeated low blows until referee Wayne Kelly had seen enough in round seven and disqualified the Polish underdog who had otherwise dominated Bowe from the sound of the opening bell. Beginning the next day and lasting for several days after, the often used phrase "a black eye for boxing" was indelibly etched on headlines, a reminder to the sporting world that boxing had again let everyone down, allowing the worst to hide the light of the best. In the 53 weeks that followed Bowe-Golota I, the black eye that began in New York became an unrecognizable, bloodied mask thanks to a series of unrelated but seemingly endless streak of unthinkable, ridiculous moments, aired live around the globe, leaving some observers wondering if the days for the Sweet Science as one of the top sports in the world were numbered.

Indeed, July 11, 1996 was only the beginning. Later that year, in Atlantic City, Golota once again dominated Bowe for nine rounds in their pay-per-view rematch before, inexplicably, getting himself disqualified by referee Eddie Cotton for repeated low blows, for the second time in six months. In February of 1997, Lennox Lewis was awarded the WBC Heavyweight Championship that he lost to Oliver McCall in 1994 when McCall suffered a nervous breakdown in the ring, crying as Mills Lane attempted to control the situation, ultimately ending the bout in one of the most bizarre technical knockouts in boxing history. In June 1997, Mike Tyson was disqualified from his rematch with Evander Holyfield, again by Mills Lane, when Tyson bit Holyfield twice in round three. In July 1997, with trouble seeming to follow the diminutive official, Lane was forced to disqualify Henry Akinwande from his WBC Heavyweight Championship fight with Lennox Lewis due to excessive holding. Four high profile fights, four disqualifications, all within little more than a year. Boxing was in desperate need of a fix, a call to fans who had gone astray to come back to the sport that had once stirred their passion rather than churning their stomach. The last chance, or so it seemed, rested with two super flyweights who hailed from the same hometown.

Although Johnny Tapia and Danny Romero were born into completely different worlds, the two young prizefighters grew up only miles apart in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The vida loca life of Tapia included the tragic, violent death of his mother Virginia under incredible circumstances, as well as the absence of his biological father. With his turn to boxing came a relationship with a local trainer associated with the Police Athletic League: Danny Romero Sr., who was also training his young son in the same weight class as Tapia. Tapia and Romero split after a brief partnership. After turning professional in 1988 following two national Golden Gloves titles, Tapia would win the USBA Super Flyweight Championship, defending it twice and placing himself in prime position for a world title shot when three positive tests for cocaine resulted in a three year suspension from boxing in 1991.

The stability that Tapia lacked proved to be a driving force in both the life and professional career of Romero. Nicknamed "Kid Dynamite" for the explosive punching power that would ultimately rank him among the pound-for-pound hardest hitters in the sport during the mid-to-late 1990s, the father-and-son team of Danny Sr. and Danny Jr. quickly ascended through the ranks of the 112 and 115 lb. weight divisions in what would prove to be a collision course with Tapia, the former Albuquerque stable mate. After winning the New Mexico State super flyweight championship in 1993 and the NABF Flyweight title in 1994, Romero realized his world championship dreams in April of 1995, on the undercard of George Foreman's title defense against Axel Schulz, with a unanimous decision win over IBF flyweight champion Francisco Tejedor.

Despite a seventh round technical knockout loss to journeyman Willy Salazar in a 1995 non-title bout, Romero would go on to win the IBF super flyweight championship in 1996 with a quick knockout of Harold Grey. With Romero's violent and exciting entrance into the super flyweight division, the unification with Tapia, then the WBO champion, was deemed both inevitable for the careers of both fighters and necessary for the good of the sport in light of troubling times.

Set to be aired before an international television audience on HBO World Championship Boxing, the long-awaited clash of the New Mexican icons was scheduled for July 18, 1997 at the Las Vegas Hilton in Las Vegas, Nevada. Although The Pit on the campus of the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque seemed like the perfect venue for the Tapia-Romero clash, concerns regarding violence between the vigorous supporters from both camps forced the relocation of the bout to a more supportive neutral site. However, the event itself was threatened in short order when an incident between Tapia and Romero supporters on a Southwest Airlines flight to Las Vegas, along with worries concerning the aftermath of the Tyson-Holyfield debacle at the MGM Grand just a month before, prompted the Hilton to pull out of the fight, leaving the Thomas and Mack Center to serve as a replacement on less than a month's notice.

The unexpected venue change was but one contributor to the volatile environment surrounding the Tapia-Romero event, with another major component existing in the form of the Tapia camp itself. In the final crucial weeks of his training camp, Tapia managed to hire and fire trainer Jesse Reid, recruit legendary trainer Eddie Futch, and later rehire Reid to work the corner as co-trainer with Futch on the night of the fight. In usual fashion, Romero remained stable, consistent, reliable, poised to work toward the task before him with brutal efficiency and a calm confidence that had defined his five year career.

Following the introductions by ring announcer Mark Beiro, the ten-thousand plus in attendance were worked into a frenzy before the sound of the opening bell. "Round one begins," HBO's Jim Lampley said as they moved to the center of the ring. "They've waited years." Indeed they had. Tapia winged hooks to Romero's body in the first minute of the opening round, dropping lead right hands on Romero as he slowly moved forward, darting in and out with the Tapia energy that brought a roar from the crowd with every significant move. With his trademark energy and defiance, Tapia finished the first round with a solid left hook and a staredown for his crosstown rival, fixing his glare on Romero as he walked back to the corner.

Despite the early effectiveness of their collective game plan, trainers Jesse Reid and Eddie Futch expressed concerns regarding Tapia's focus, urging him to remain disciplined, to move in and out, counter when necessary, and to avoid a toe-to-toe war with his power punching counterpart who had scored 27 knockouts in his 30 wins. The Tapia body attack and frenetic pace continued in rounds two and three, but Romero would finally come alive and capture the momentum in round four, moving inside the Tapia attack while landing jabs and right hands with regularity. With Romero taking charge, landing his best punches of the fight in round five, making his physical presence felt, and disturbing Tapia's rhythm, the fight appeared to be in a dead heat going into the final six rounds.

In the opening seconds of round seven, a Romero right hand cracked Tapia flush on the jaw, prompting Tapia to clown, feign being hurt, and touch his gloves to the canvas. That shot from Romero would prove to be one of his final big moments in the ebb and flow of the fight. Later in the round, following an accidental clash of heads, as Mitch Halpern checked both fighters, Tapia walked toward the corner and asked, "Are you okay, Danny?", an event thought impossible little more than an hour before. The resurgent Tapia worked back into the game plan that won the first three rounds, boxing Romero in rounds seven and eight, circling to his right, working behind the jab, and avoiding a Romero attack that was growing progressively slower and more predictable as the IBF champion looked for the knockout blow that would settle the score between the longtime rivals.

"Play with him! Play with him! He's getting frustrated," Jesse Reid said emphatically, dispensing almost unheard of advice in the Tapia corner before the start of the tenth round, and yet that is exactly what Tapia would do in the final three rounds. With energy now shown since the first third of the bout, Tapia exploded with combinations to the body and head of Romero in round eleven, drilling his opponent in the center of the ring and raising his hand between the attacks, prompting cheers and chants from the predominantly pro-Tapia crowd.

Before the twelfth and final round, Jesse Reid told Tapia to have some fun with Romero and to look like a true champion. Across the ring, Danny Romero was given more tactical advice, to fire punches at Tapia and keep him from doing too much. For the boxing world, the question that remained was not which fighter would be awarded a decision when the final three minutes had elapsed, but how much the fight could do to heal the wounds of the last 53 weeks and whether or not the final verdict would settle the score between Tapia and Romero in a sense that extended far beyond the ring at the Thomas and Mack Center.

In the twelfth, Tapia boxed and Romero stalked, but neither fighter took the round decisively. As the bell sounded, Tapia delivered a trademark backflip and was raised in the air by Jesse Reid. Both fighters raised their arms to the crowd, with Tapia receiving the louder ovation as he stood on the ropes and pointed skyward. The same gesture from Romero drew a chorus of boos just seconds before Mark Beiro called for the bell and read the decision.

Judges Clark Sammartino and Jerry Roth scored 116-112, while Glen Hamada scored 115-113, all in favor of Johnny Tapia, but the sport in desperate need of a great fight on a big night, full of excitement and free of controversy, was the true winner. A tearful Tapia celebrated with the grandfather who raised him during the postfight interview while a disappointed Romero considered the possibility of a rematch and pondered his own future, one no longer linked to Tapia, with the class that was expected of the two-time world champion. More importantly, both men sought to let the comments and events of the past stay in the past.

In an unexpected turn of events, the careers of Tapia and Romero would ultimately go in different directions. Tapia would continue on at the highest levels of the sport, defending his unified IBF/WBO championship twice before defeating Nana Konadu for the WBA bantamweight championship, a title he would lose to Paulie Ayala in 1999, the first defeat of Tapia's career. There was one more title belt for the collection, an IBF featherweight championship won from Manuel Medina in 2002, before the erosion of his skills was made evident in a lopsided twelve round loss to Mexican legend Marco Antonio Barrera in 2002.

For Romero, the narrow loss on the biggest stage of his career would serve as his personal pinnacle. His bid for the IBF super bantamweight title fell just short in a majority decision loss to champion Vuyani Bungu on Halloween night 1998 in Atlantic City. Romero would not challenge for a major world title again. There were eight more wins for the record, followed by a decision loss to Ratanachai Sor Vorapin in 2001 and a TKO loss to Cruz Carbajal in 2002. A short comeback netted two wins and a draw for Romero, who has not fought since 2006.

Neither Tapia nor Romero stepped into the ring in 2008 or 2009, with Romero seemingly retired and Tapia recently serving a jail sentence that actually caused the cancellation of a possible comeback fight in Albuquerque. Looking back, it's hard to believe that the long-awaited clash to unify the IBF and WBO super flyweight championships, and to award bragging rights over the mutual hometown of two of the best small fighters in the world, took place nearly twelve years ago. Although the official record shows Johnny Tapia winning a unanimous decision over Danny Romero in Las Vegas, boxing fans around the world should remember that night as an example of what the sport can ultimately be: an exhibition of pure boxing skills, filled with controlled emotion, a wealth of talent, and incredible energy, devoid of controversy, violence, and disgrace. For that night, while forgotten by some, those who passionately follow the sport should be forever grateful, because on a hot July night in the Las Vegas desert, rather than being administered another black eye, the world of boxing was presented with a Silver Star.

The New York Times write-up in the battle for Albuquerque the day after the fight.

Tapia Pounds Romero To Win Grudge Match

One of them tried the oldest move in the book (sticking out his tongue) and the other tried a more up-to-date tactic (the right jab). They held the battle of Albuquerque in the suburb of Las Vegas tonight, and some think the loser should have to walk home to New Mexico.

In that case, Danny Romero had better start thumbing a ride. Romero, 23 and fed most of his life from a silver platter, lost to a 30-year-old showboat, Johnny Tapia, this evening in a junior bantamweight (114 pound) title bout that got boxing back to its basics: brawling.

Tapia, in a unanimous decision, unified the International Boxing Federation and World Boxing Organization belts at the Thomas and Mack Center -- and nearly broke Romero's pug nose.

''Go get me that belt; go get me that belt,'' Tapia said afterward. ''Put that belt on me.''

The fight was officially three years in the making, but it was actually more like 16 years. The fighters first met at a Police Athletic Club (Tapia was 14, Romero was 7), although Romero would go home to his father and trainer, Danny Sr., and Tapia would go home to absolutely nothing.

Tapia, at the age of 8, witnessed the murder and rape of his mother, and he had been estranged from his father from birth. ''I've been poor,'' he said before the fight. But he left the building tonight with a $400,000 check and was an absolute wreck, too.

''I dedicated this fight to my mom,'' he said, ''because I miss her. And I did it.''

Danny Romero Sr. had actually once been Tapia's trainer, but they split unceremoniously, and the grudge remains.

Tapia on Romero Jr. before the fight: ''I hate him, I hate him.''

Romero Jr. on Tapia: ''Going out and acting like an idiot is not my nature. I'll leave that to someone else.''

Now there appears to be no end to the grudge. After the unanimous decision -- the judges had it even after eight rounds but scored it 116-112, 116-112 and 115-113 in the end -- Tapia said: ''Let's let bygones be bygones. It's over.''

But Romero Sr. would not buy it. In fact, when Tapia sauntered over to shake the younger Romero's hand, the father waved Tapia off.

''He's a you-know-what,'' Tapia said of Romero Sr. ''Always has been.''

Romero Jr.'s response was, ''I thought I won.''

Of course, Tapia (41-0-2) cannot keep a straight face anywhere, much less in the ring. He stuck out his tongue at Romero, and when Romero landed a rare dead-on punch in the seventh round, Tapia feigned that he was about to fall down.

''He never caught me clean,'' Tapia said of Romero (30-2).

Certainly, they prepared for this fight differently. Romero did not spar a single round, drilling with his father instead, while Tapia spent the last few months firing three trainers.

''Well, when there's nothing going wrong in my life, there's nothing right,'' he said of his parade of trainers. ''All I really need is somebody to give me water in the corner, anyway. I'll take care of the rest.''

Actually, he had Jesse Reid and the Hall of Famer Eddie Futch in his corner tonight, and he executed their plan exquisitely. He went to Romero's body with left hooks, to his face with straight rights, and moved to the right after every punch.

The rematch would sell out any arena in New Mexico, but do not hold your breath.

''No, no rematch,'' Tapia said. ''It's too easy of a fight.''

More comments from Tapia and Romero after the fight:

“I never wanted to knock him out – I just wanted to punish him,” said 30-year-old Tapia who retained his WBO strap and took Romero’s IBF belt.

“The game plan was to stick and move, keep moving to my right and make it an easy fight. And that’s what it was. It was so easy.”

“I thought I won,” Romero, 23, said. “A few things maybe I could’ve done better, but that’s the way it goes. It didn’t come out the way it should’ve, but hey, more power to him.”

After all the drama that unfolded in the story of the battle for Albuquerque, Johnny Tapia and Danny Romero Jr became good friends. They forgave each other for all the ugly things they’d said and became buddies, even traveling to fights together. There's a lot of heat in the boxing world, a lot of pride, a lot of competitiveness, it is after all the business of battle. But at the end of the day, there's really a deep respect between fellow warriors.

The Tapia-Romero fight was a master performance from Tapia, a 30-year old outwitting a 23-year old young hungry lion with a monster punch, and using the science of boxing to get it done. Just a masterful performance from Tapia.

Tapia is a legend, a polarizing figure in not only boxing history but sports history. He wrote his own autobiography entitled "Mi Vida Loca" before he died, and has another book written about his life entitled "The Ghost of Johnny Tapia", the foreword to that book was written by the famous Van Halen frontman Sammy Hagar, Hagar was a huge Tapia fan, and Tapia also has an HBO documentary about him. He had to fight his whole life, inside the ring, outside the ring, he was always fighting something, whether it be personal demons, fighting for his sanity after all the tragedy that was bestowed upon him, or literally fighting for his very life. Even before he was born, tragedies were already occurring in Tapia’s life with the murder of his father while his mother was pregnant with him. Then the tragedy of his mother being murdered, At just eight-years-old Johnny witnessed his mother, Virginia, being kidnapped away from their home. She was chained to a truck, brutally assaulted, raped, stabbed 22 times, and left for dead, but she fought and crawled more than a hundred yards before being found by police and taken to the emergency room. Sadly, she passed away a few days later. The sights and sounds of his mother’s last days forever haunted him. He told Boxing News in 2011, “My mom’s death kills me every day…I just want to say ‘Good night mama.’ I want to hug my mama.” By the age of eight, Tapia found himself an orphan. There was a lot of pain and pent-up frustration within Tapia, and it was no surprise when he turned to boxing at the age of nine while under the care of his grandparents. Rich kids don't fight, poor kids fight, and Tapia had to fight his way out of poverty, and the insanity around him. As a young boy, Tapia was matched in fights against other neighbourhood children for his family to bet on. By now, boxing wasn’t a hobby. It was a necessity. Tapia described his life as: “Raised as a Pitbull. Raised to fight to the death.” And in his life, there were many fights with death. Tapia's brother-in-law, Robert "Gordy" Gutierrez, and nephew, Ben Garcia, were killed in a car crash on March 13, 2007. They were on their way to visit Tapia in the hospital in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he had been admitted for a cocaine overdose, Tapia blamed himself for the tragedy. He overdosed on drugs and was declared dead four separate times in the hospital, he fought his addiction until the day he died, but ultimately lost his life to drugs. The man was a fighter. Put it this way, if I was going to fight in a war and had to share a foxhole with someone, besides my family, Tapia would be next to me in that foxhole, because like me, he knew what it was like to have to fight the hells of life everyday and would never stop fighting for the good. I think Johnny Tapia knew he was never going to make it alive into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. He had way too many addictions, way too many demons. The only place Tapia ever felt peace was in the ring itself. Johnny always said that when his career was over, he didn't know what he was going to do with himself and probably wouldn't last long. He lasted one year from when he quit boxing. Tapia himself never thought he would live past the age of 40. He reached 45 before his tormented life finally came to an end at his home in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

This is a photo of Johnny Tapia with his wife Teresa Tapia, she managed his career and was a steady influence in his life. Johnny never defeated his demons, but he fought them, because of his relationship with his wife Teresa he had hope until the very end despite all the darkness he walked through.

Let's get a few photos of Johnny Tapia in here. This is an image of Tapia with the legendary Mexican fighter Marco Antonio Barrera, aka "The Baby Faced Assassin", they were good friends and had a deep mutual respect for each other. They actually fought in 2002 with Barrera getting the decision victory. They respected each other so much that they had eachother's last names embroidered on their trunks when they fought, and after Tapia passed away Barrera always fought with Tapia's name on his trunks.

34-year-old Carl Froch, aka "The Cobra", mauled the murderous punching IBF super-middleweight champion Lucian Bute in five rounds in his hometown of Nottingham in 2012.

"After the Andre Ward defeat I was very, very deflated. I was here to put right a wrong," Froch told Sky Sports. "I was more determined than ever before.

"I was very switched on, focused and determined. I came here to do a job. If it had gone 12 rounds it would have been 12 rounds of that. I was on it.

"A lot of people wrote me off. The bookies got it wrong, and a lot of people in Nottingham have won some money tonight.

"I could not afford to be lazy and flat-footed. Big respect to Lucian, he can punch, and he hit me with some good shots in there. But I came back."

My favorite Carl Froch moment was his one punch knockout of George Groves in 2014 at Wembley stadium, it was the knockout of the year. This was the epic rematch that saw Carl Froch knock out George Groves with what proved to be the final punch of Froch's legendary career and close the book on their bitter rivalry. Groves was a damn good fighter himself, but got caught cold with a brutal right hand. Froch was in his 12th year as a pro and had mentioned retirement. He just missed winning the Super Six tournament against Andre Ward, then rebounded with a massive stoppage of Lucian Bute and two more wins before facing Groves in their first fight.

Groves, a former British super middleweight champion from London who was undefeated but hadn't scored a signature victory. He was a good puncher with solid technique, and his speed advantage helped him drop Froch in the 1st round of their first bout. Froch then clawed his way back before scoring a controversial stoppage, setting up a rematch.

Both fighters talked trash going into the rematch and the drama helped lead to good ticket sales as 80,000 or so spectators watched a classic—a figure Froch wouldn't soon let anyone forget.

Groves was more tentative this time around even though he pledged to knock Froch out in three rounds. Froch was sharper and clipped Groves when he did open up, making him even more tentative. Froch's singular focus on a knockout helped him avoid a war in round 5.

In round 7, Froch appeared to rock Groves. And in the 8th, Froch unloaded a sizzler of a right hand that flattened his rival. Grove went down awkwardly and his left leg got bent grotesquely to the side of his body, he stayed motionless, then the fight was waved off as Groves moved to get to his feet as it became clear it was over, but it was way too late.

“This was a legacy fight,” Froch said. “Unfortunately in boxing, people remember you for your last fight. I didn’t want to go out to be remembered as being a loser, and I would have retired if I’d lost tonight.”

‘It took years off my life’ – heavyweight Fabio Wardley lived off ice cream and noodles after his brutal fight with Frazer Clarke in March of 2024.

Wardley resorted to a diet of ice cream and noodles after the pair put on a thriller over 12 rounds that ended in a draw.

Wardley was left covered in blood due to his busted nose and a jaw injury that left him barely able to chew in the days after.

He told The Sun Times: “It’s a fate that you have to accept if you do this sport properly.

“I probably should’ve gone to the hospital afterwards. I remember being sat in my hotel room and I couldn’t sleep because my head was pounding, like vibrating.

"When I lay down, I felt sick. If I sat up, I felt sick. My face looked like the Elephant Man. My nose was stitched up."

"I’d bitten my tongue about 100 times. I couldn’t chew for three days because of my jaw, so I just ate ice cream and noodles, but that’s part of it."

“Those fights are going to happen and you might get knocked out, but if you carry that around with you and hesitate because you’re scared of it, it could have a negative impact on how you fight and almost make it more likely to happen. You’ve got to just take it on the chin.”

Wardley scored a knockdown in round five and Clarke had a point taken off to even the judges scorecards.

But Wardley won the rematch six months later with a brutal first-round knockout that left Clarke hospitalised.

Just five months after Tim Witherspoon captured the WBC Heavyweight Title by defeating Greg Page, he stepped into the ring to defend it against the undefeated Pinklon Thomas. With Larry Holmes vacating the title to be recognized as the IBF champion, the stage was set for a new heavyweight king to emerge.

The opening round saw both fighters feeling each other out, but from Round 2 on, Thomas took control. His jab—powerful and relentless—repeatedly found its target, frustrating Witherspoon and leading to complaints to referee Richard Steele. No fouls were called, and Thomas continued to dominate with skillful distance control and sharp boxing.

By Round 9, Thomas had built a clear lead. He coasted through the final rounds, avoiding risk and staying in command. Though one judge controversially scored it a draw, the other two awarded Thomas a well-deserved majority decision. Most observers agreed that Thomas was the rightful winner.

What made this victory even more powerful was Thomas's backstory. Raised in Pontiac, Michigan, his youth was consumed by addiction and violence. He was using heroin by 12 and hooked by 14. But his life changed when he married Kathy Jones, followed her into the Army, and discovered boxing with the help of trainer Joe West. Under the guidance of the legendary Angelo Dundee, Thomas turned his life around and became a world champion.

For Witherspoon, the loss was tough. It ended his title reign after just one defense, and financial distractions had weighed heavily on him throughout the fight buildup.

Thomas would go on to defend the WBC title twice before losing it to Trevor Berbick in 1986. Witherspoon, too, bounced back, briefly reclaiming a portion of the heavyweight crown before losing it again.

This fight remains a symbol of Pinklon Thomas’s incredible journey—from addiction and hardship to the very top of the boxing world.

The legendary trainer Angelo Dundee was once asked who was the hardest puncher he ever trained, and he said Florentino "The Ox" Fernandez was the hardest puncher he trained, but he also said "Pinklon Thomas could really whack." One thing about Pinklon Thomas, he had a masterful left hand, he could really punish you with that left. He could use it as a jab and pepper you with it, or he could use it as a hook, either way he could really bust you up with it.

The great Emile Griffith with his legendary trainer Gil Clancy. Clancy trained Griffith throughout his professional career, guiding him to world championships in the welterweight and middleweight divisions. He began training Griffith in the amateur ranks and continued with him for his entire 19-year professional career.

"I worked Emile Griffith's corner for over 120 rounds, and after every one I'd say something to him. He asked me, 'Don't I ever do anything right?' I said, 'You do almost everything right. But I'm looking for the perfect round.'' - Gil Clancy

The immortal Emile Griffith is one of the greatest pound-for-pound fighters that ever lived, great welterweight, great middleweight. Unfortunately he's probably best known for his third bout in 1962 with Benny Paret, in which Paret died as a result of his injuries. But Griffith was a true all-time great, you're talking about a man with victories over Dick Tiger x2, Luis Rodriguez x2, Bennie Briscoe, Joey Archer x2, Nino Benvenuti, Gaspar Ortega x2, Florentino Fernandez, Holly Mims, Yama Bahama, Dave Charley, Benny "Kid" Paret x2, Willie Toweel. Griffith was the first man to ever knock down the iron chinned Dick Tiger, and he was the first and only man to defeat the legendary "Gypsy" Joe Harris. Simply put, you drop prime Emile Griffith in any era and he raises hell.

EMILE GRIFFITH - AGAINST THE ODDS

Feb 2, 2025

‘If I lost, I was determined to get them back and beat them. Losing made me more determined.’ -Emile Griffith

Emile Alphonse Griffith was born on 3 February 1938 on the U.S. Virgin Island of Saint Thomas. Shortly after birth, his father took off and unfortunately, the most prominent male figure in his childhood memories was a man who molested young Emile, traumatising and emotionally scaring the youth for life.

Griffith’s legacy is remembered by many for a few reasons - namely, being involved in a fight which resulted in his opponent’s death, but also his sexual orientation. What many fail to initially mention is that he was a multi-weight world champion who was only stopped twice in 112 professional fights.

At the age of 19, Griffith moved to the bright lights of New York, working as a stock boy at a hat factory run by former amateur boxer, Howard Albert. Despite setting his heart on a future as a milliner, one day, Griffith was working shirtless, when Albert spotted his physique and encouraged him to try boxing at his friend’s gym, run by non-other than Gil Clancy. This was the start of an incredible friendship and partnership between the trio, which would see Griffith managed and trained by the pair. Young Emile went from dreams of making hats to making pugilistic history.

Within months of first donning the gloves in 1957, Griffith reached the finals of the welterweight division, but was defeated by Charles Wormley, who fought out of the Salem Crescent Athletic Club. However, in 1958 Emile’s fistic trajectory started to rise at a step gradient. Still competing in the 147lbs division, Griffith won three tournaments on the bounce, namely, the New York Daily News Golden Gloves Championship, where he defeated Osvaldo Marcano on 24 March 1958, the Intercity Golden Gloves Championship against Dave Holman and lastly, the New York Golden Gloves Tournament of Champions.

Guided by Clancy and Albert, the 20-year-old, standing a touch over 5ft 7 inches, made his professional debut on 2 June 1958, defeating Joe Parkham on points at St. Nicholas Arena, New York. Over the next 11 months, Griffith fought a further 11 times at the same venue, bringing his record to 12-0, with five stoppages.

On 7 August 1959, Griffith headlined at Madison Square Garden against the former Cuban welterweight champion, Kid Fichique, winning a comfortable points decision over 10 rounds. On the undercard was another Cuban by the name of Benny Kid Paret, who would play a big part in Griffith’s future.

Two months later, Griffith lost his first pro contest against Randy Sandy (great name) via split decision. Undeterred by the loss, the Virgin Islands native fought a further 10 times over the next 14 months against some study opposition, including world title challenger and Commonwealth champion, Willie Toweel, bringing his record to 22-2.

Less than three years after turning professional, on 1 April 1961, Griffith took on the world welterweight champion, Benny Kid Paret at the Convention Centre, Miami Beach. One minute and 11 seconds into the thirteenth stanza, Griffith stopped Paret, in a contest which was neck and neck up to that point, with one judge edging it to Griffith, one to Paret and the other who saw it a draw. The pair would inevitably meet again very soon.

Griffith v Paret 1961

Two months later, Griffith defended his title against Mexican, Gaspar Ortega, knocking him down twice in the seventh round, before stopping him in the twelfth. The first title defence tasted that much sweeter, because the pair had locked horns in February 1960, which saw Griffith taking a split decision victory, whilst the crowd booed, believing Ortega had dominated the contest. Griffith took the decision out of the judges hands this time round.

On 30 September 1961, Griffith attempted to defend his welterweight crown against Paret at Madison Square Garden, in another brutal contest, which saw the Cuban clinch a split decision victory over 15 rounds.

Not one to lick his wounds, Griffith fought three times in the next five months, clinching victories in Bermuda, America and his native Virgin Islands. Inevitably, the rubber match with Paret was set up and the pair met for the third time on 24 March 1962 at Madison Square Garden. However, this time the mood was different going into the fight. Paret had thrown homophobic slurs at Griffith, calling him a ‘maricón,’ which was the English slang equivalent of fa..... At a later date, Griffith said in an interview with Sports Illustrated, ‘I like men and women both. But I don't like the words, homosexual, gay or fa..... I don't know what I am. I love men and women the same, but if you ask me which is better, I like women.’ You have to remember that homosexual behaviour was illegal in some form, in most states in America, right up until the 1970’s and Griffith had no issue in expressing his sexual tendencies, which caused him to endure some disgusting treatment from society throughout his existence. His admission of being bisexual was believed to have been the transparent cover up for being gay in an alpha male existence.

To say Griffith went into the third Paret fight enraged was an understatement. The fight kicked off in its usual high octane manner, which saw Griffith take an eight count in round six and was close to being stopped if the bell hadn’t sounded for the end of the round. From the seventh onwards, Griffith came out like a man possessed, unleashing suffocating volumes of punches on Paret in what can only be described as a merciless beating. Going into the twelfth round, Griffith was well ahead on points and knocked Paret out cold. The ropes unfortunately held up the unconscious Cuban, whilst Griffith took no chances and continued to unload his arsenal until the referee finally stepped in. The fight was being transmitted live by ABC and was so shocking that they refused to run a live boxing show for a further 20 years.

Unfortunately, Paret never regained consciousness and passed away 10 days later on 3 April 1962 at the Roosevelt Hospital. Many believed Griffith wanted to intentionally kill Benny, but this was far from the truth. Yes, he was angry, but he was no murderer. In the minutes and hours that passed immediately after the fight was halted, Griffith realized Paret’s condition was very serious and immediately headed to the hospital, albeit, he was never allowed access to see his foe. The fight was investigated by the New York Governor, Nelson Rockefeller and despite both Griffith and the referee being cleared for any wrongdoing, the Paret death is an episode that would haunt Griffith until his dying days.

Griffith said at a later date, ‘I kill a man and most people understand and forgive me. However, I love a man, and to so many people this is an unforgivable sin; this makes me an evil person.’ Thankfully, over 40 years after the tragedy, Griffith was able to meet with Paret’s son, who told Emile, ‘I need you to know something. There’s no hard feelings.’

Four months after Paret’s passing, Griffith defended his welterweight strap against Ralph Dupas, defeating the New Orleans resident comfortably on points over the 15 rounds duration. In his next two fights, he fought north of 150lbs, defeating natural middleweights, Don Fullmer (Gene’s brother) and Denny Moyer, who he had previously lost to in 1960.

Griffith v Dupas 1962

On 17 October 1962, Griffith beat Michigan boxer, Ted Wright in Vienna, Austria, to be crowned the world light middleweight champion, in a one-sided contest. However – the title was only recognised by the Austrian Boxing Board of Control, which meant in the public’s eyes, he was not a true champion. Ironically, as the alphabet soup of straps started to emerge, the first two officially recognised middleweight champions (WBA & WBC), from 20 October 1962 – 7 April – 1963, were……Denny Moyer and Ralph Dupas, both of whom Griffith had defeated back to back three months earlier.

After defending his Austrian recognised light middleweight world title against Dane, Chris ‘The Gentleman’ Christensen in Copenhagen, Griffith fought Cuban born Miami resident, Luis Rodriguez for the WBC world welterweight crown. The WBC title had already been awarded to Griffith in December 1962, as an inaugural title, but he never felt like the champion until he fought in the ring for it. Unfortunately, after 15 hard fought rounds, Griffith lost the fight on all three judges scorecards, however, not all was lost.

Just over two months later, on 8 June 1963, the pair locked horns again at Madison Square Garden. Once again, both fighters worked their trunks off in a close fight, but this time, Griffith did enough to grind out a split decision victory and in doing so became the new WBC world welterweight champion.

Griffith fought three more times in 1963, in non-sanctioned contests, one of which included a shock defeat against hard hitting Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter on 20 December, which saw Emile hit the canvas twice, before the contest was called to a halt in only two minutes and 13 seconds of the opening round.

1964 saw Griffith hit the road as he travelled to Australia, Italy, Hawaii, Las Vegas and even a couple of visits to the UK. Emile added five further victories to his CV, which included one no-contest, a title defence and rubber match victory over Luis Rodgriguez, plus a points defence over Brian Curvis at the Empire Pool, Wembley, which saw Curvis hist the canvas in rounds six, 10 and 13. Two months after beating Brian, Griffith beat fellow Brit, ‘The Dartford Destroyer,’ Dave Charnley via ninth-round stoppage.

The year after was a mixed bag. Griffith lost his opening contest of the year against on points in a non-sanctioned fight against Manuel Gonzalez, followed two months later in March 1965 by a successful WBC welterweight title defence against Jose Stable. Two fights later he lost a points decision against old foe, Don Fullmer for the WBA American middleweight title, followed by three victories, which included another successful title defence against Manuel Gonzalez, avenging his loss earlier in the year.

Griffith only fought three times in 1966, which in current day terms would be considered a full quota for a world champion. However, it was certainly the quality of the fights that counted, not the quantity.

After a warmup fight in February 1966, on 25 April, Griffith defeated teak tough Nigerian, Dick Tiger to retain his welterweight crown. Three months later, on 13 July 1966, Griffith beat Joey Archer on a majority decision for the WBC world middleweight title, cementing his place in history as a two-weight world champion. It’s worth noting that Dick Tiger was a natural 160lbs fighter and former world middleweight champion and only eight months after his defeat to Emile, beat Jose Torres to become world light heavyweight world champion. He was far from a washed-up fighter and a further clash with Griffith down the line was inevitable.

Griffith’s time at middleweight was far from a flash in the pan. It would in fact be a defining period in his fistic career, which unfortunately was littered with some of the best middleweights to walk this planet. In another era, Emile may have ruled the 160lbs roost for several years.

Six months after winning the title against Archer, he rematched the New York native and once again won by a slim margin on points. Three months later, on 17 April 1967 at Madison Square Garden, Griffith lost his middleweight crown against future Hall of Famer, Nino Benvenuti in a barnburner of a contest. After being floored in the second round, Griffith repaid the favour to the Italian in the fourth round and the pair battled it out for the full 15, with Benvenuti taking a convincing points decision in what was 1967 Fight of the Year for Ring Magazine.

Over the next 11 months, Griffith and Benvenuti fought a further two times. On 29 September 1967, Griffith knocked down Benvenuti in the fourteenth and despite one judge seeing the contest a draw, the other two had Emile winning by four rounds. He was now a two-time middleweight champion.

Six months later, on 4 March 1968, the pair met once again at Madison Square Garden, in a contest which was down to the wire going into the championship rounds. Unfortunately for Griffith he hit the canvas in the penultimate round, which marginally swayed the judges Benvenuti’s way. This would be Griffith’s last fight as world champion, albeit he was still in the mix at world level for several years to come.

Over the next three years, Griffith extended his record to 70 victories, 11 losses, which included an unsuccessful attempt at the WBC welterweight title against Jose Napoles and a non-sanctioned victory over Dick Tiger.

On 25 September 1971, Griffith made a gutsy attempt to dethrone the new WBC middleweight king, Carlos Monzon in his backyard of Estadio Lunar Park, Buenos Aires. Monzon, possibly one of the best ever middleweights, had ripped the title away from Benvenuti with a twelfth round stoppage in 1970. Four months prior to facing Griffith, he fought Benvenuti once again, but this time crushing the Italian in three rounds. Despite giving it his very best shot, Monzon was far too much for 33-year-old Emile, who was stopped by the Argentinian in the fourteenth round.

Over the next three years, Griffith clocked up a further six victories, one draw and one disqualification loss (due to a low blow) and attempted to beat the iron fisted Monzon once again, but this time at the Stade Louis II, Monaco. Despite many writing Griffith off as the heavy ageing underdog, he put up a solid performance, taking Monzon the distance in a fight which saw two judges giving the Argentine victory by three rounds and one by two rounds.

On 18 September 1976, Griffith took on German, Eckhard Dagge for the WBC world super welterweight title. Since the last Monzon loss, Emile’s resume now read, 82 victories, 20 losses and two draws, which included losses against the likes of Tony Mundine, Vito Antuofermo and victories over Bennie Briscoe. At 38 years of age, Griffith was given little chance of upsetting the odds, but once again, he pulled out a standup performance against Dagge, losing a debatable majority decision in the German’s backyard.

Griffith fought a further six times, with his swansong being against Alan Minter in Monaco on 30 July 1977. Having just turned 39 years old, Griffith thankfully hung up the gloves shortly after. His record, in a career which spanned almost 20 years, was 85 victories, 24 losses and two draws. Let’s also not forget he was a very respected two weight world champion who was always willing to share the ring with the best of the best.

Griffith went on to help train a number of fighters, including world champions, Juan Laporte, James Bonecrusher Smith and Wilfred Benitez and even had a brief stint in the late 70’s as the Olympic Danish boxing coach.

1990 saw Griffith rightly inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. Director, Ed Brophy said of Griffith, ‘Emile was a gifted athlete and truly a great boxer. Outside the ring he was as great a gentleman as he was a fighter.’

Sadly, in 1992, Griffith was the victim of a savage and sickening homophobic beating in New York, which left him hospital bound for a substantial amount of time, recovering from life threatening injuries to his head and kidneys.

Emile Griffith died on 23 July 2013 in a care home in New York, at the age of 75 from kidney failure, relating to dementia and was buried in St Michael’s Cemetery in Queens, NYC. He was a fast punching world champion with great footwork, a beautiful jab and defensive skills to match, who would have been world champion in any era. No doubt about it.

You can't talk about Emile Griffith without talking about tragedy that overshadowed his career, so Let's get this off our chest, Emile Griffith-Benny Paret III, 1962. Unfortunately this is the fight that Emile Griffith is best remembered for, and it's a shame because Griffith had such a long and brilliant career. Paret had made a homophobic slur towards Griffith before the fight and it hurt Griffith tremendously, I think he fought angry that night. The fight itself was a back and forth war, and the outcome was tragic. But it happened. A documentary was made about the tragedy called: Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story, and a book was also written about it entitled: A Man's World.

The Fight City

The Nightmares Of Emile Griffith

Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story

The story explores the ramifications of one of the most infamous moments in the history of professional boxing. On March 24, 1962, at Madison Square Garden in New York, Emile Griffith pummelled Benny “The Kid” Paret to death, live on national television. Though he went on to become a five-time world champion, in the process amassing a small fortune in prize money, a wardrobe of fifty designer suits, and a pink Lincoln Continental, the horror of having killed a man would haunt Griffith for more than forty years. Still, he achieved professional success because early in his career he’d resolved, “I wasn’t nobody’s fa.....”

Ring-of-Fire

When Griffith began to dominate the welterweight division in the early 1960s, homosexuality was deemed a disease, a crime against nature, as it still is today, though to a marginally lesser extent, human progress being a game of inches. Perhaps because in addition to prizefighting Griffith was a professional hat designer, other boxers on the circuit thought he was gay and ridiculed him for it, especially Paret, with mortal consequences. Griffith’s avenging rage would lead him down a long, tortuous path toward wisdom and forgiveness, neither offering consolation nor lessening the anguish borne of his tragic victory.

The documentary does excellent work of fleshing out both Griffith and Paret as complex human beings, shattering the stereotype of the boxer as heartless brute. More than four decades after Paret’s death, his wife Lucy hadn’t remarried because she “didn’t want [their] kid brought up by anyone else.” She describes Paret as a devoted husband and an affectionate father to his infant son Benny Jr., whom he wanted to become a doctor or lawyer, not an illiterate boxer like him.

But like so many other fighters, he was exploited by his manager, Manuel Alfaro, who’d imported Paret from Cuba and thought he owned the two-time world champion. The film puts most of the blame for Paret’s death on Alfaro. Paret had lost his last five fights and just three months before the fateful one against Griffith, he’d been clobbered in a career-ending rout by Gene Fullmer, who said, “I never beat anybody worse than him.” After such a beating, a manager’s supposed to give his “boy” a few easy fights to build back his confidence, but Alfaro, hungry for cash, threw Paret back in the ring with Griffith, one of his toughest opponents. As Paret lay dying on the mat, Alfaro is alleged to have said, “Now I have to go find a new boy.”

Paret, however, did taunt Griffith before their second and third fights, calling him a maricon, Spanish for ‘fa.....’ Prior to the third match, an article in The New York Times, entitled “Paret and Hat Designer Griffith Gird for Welter Title Fight,” referred to Emile as an “unman.” In the film Griffith relates the impact of Paret’s slurs and the media fixation on his then-alleged homosexuality (he came out in 2008): “When I had [Paret] in the corner in the twelfth round, I was very angry. Nobody never called me no fa.... before.” And yet Griffith doesn’t strike one as a brutal killer.

According to his biographer Ron Ross, at the start of his career Griffith was “reluctant to become a fighter.” When ahead on points his aggressiveness would wane; his trainer Gil Clancy “really had to instil the killer instinct in him.” Griffith was devoted to his family and used the money he earned from his first eight fights to bring his mother and seven brothers and sisters, one by one, from the Virgin Islands to New York. Portrayed as a man of depth and sensitivity, obedient to his trainers, yearning both for a father figure and to be a father himself, Griffith later adopted a juvenile delinquent when, after his retirement from boxing, he became a youth house corrections officer.

The film’s sympathetic portrait of Griffith contradicts the picture author Norman Mailer painted of him in strokes of gross hyperbole. According to Mailer, during the twelfth-round knockout Griffith was making “a pent-up whispering sound all the while he attacked, the right hand whipping like a piston rod which has broken through the crank case, or like a baseball bat demolishing a pumpkin …Griffith was uncontrollable. His trainer had leaped into the ring, his manager, his cut man. There were four people holding him, but he was off on an orgy … If he had been able to break loose, he would have hurled Paret to the floor, and wailed on him there.”

In fact, Griffith looked measured and focused as he punished Paret in the corner. Griffith didn’t go “off on an orgy,” and when the referee—never his trainer, manager, cut man or anyone else—finally stepped in, Griffith obediently withdrew and showed meagre enthusiasm for his victory. It was those around him, namely con artists like Mailer, and the gangsters and politicians in the front row, who went “off on an orgy” of bloodlust for the violence of boxing, violence that rarely rivals the kind we exaggerate, distort and fetishize on television and in other forms of mass entertainment.

The live footage of the events that took place after Paret’s collapse provides far more damning evidence of human cruelty and callousness. In a moment of blood-curdling irony, with Paret on the mat slowly dying, Griffith is interviewed at ring centre. The interviewer asks “to replay the knockout in slow-motion videotape,” and as we watch Griffith pounding Paret’s head with inside uppercuts of pin-point accuracy, the interviewer quips, “That’s beautiful camera work, isn’t it?” Someone off-camera shouts, “Terrific!” I imagine it would have been even more “terrific” if chunks of Paret’s “pumpkin” had pelted the audience, spraying from his temples in flakes and strings.

The fallout from Paret’s televised death, after being replayed day and night for weeks, included sponsors pulling ads from Friday Night Fights. Then boxing was banned from television for more than a decade, which brings us to a second bone-chilling irony: the reason Paret was so popular among matchmakers and sponsors was because he could take a beating for ten rounds without getting knocked out, securing nine rounds of commercials before viewers changed the channel.

But with Paret’s death, boxing became a scapegoat for Americans’ collective guilt over its violent spirit and history. Who would admit to the frisson they felt at watching a man die on live television? The tragic spectacle and its aftermath aroused an orgy of hypocrisy and, in Clancy’s cutting phrase, “an occasion for one of these epidemics of piety.” Besides, the heyday of boxing is long gone, the sport enduring a slow decline, surmounted by even more violent sports, like mixed martial arts, where watchers can fantasize about a heel-kick shattering an orbital bone, the eyeball swinging from its socket like a clapper.

“This is a cold, cruel world! Come on, get going!” As much as such sentiments offer wisdom and practical advice for one who struggles, albeit briefly, with his conscience as he considers crushing another to climb the ladder of success, in fact reporter Jimmy Breslin used these words to admonish Griffith to get over the fact he’d killed a man. But Emile could not. Forty-three years after the tragedy, Griffith, restive and trembling, tells the film’s interviewer: “My friend, I sit here talking to you, I can still feel … I-I-I feel … Oh gosh … I get chills, you know, talkin’ about him. Sometime I still have nightmares … I wake up sometime, I feel my sweat all over my face, I don’t know … Memories come back, there’s nothing you can do about it. Just let it flow.”

I cannot imagine the ceaseless stream of guilt and torment that flows from the knowledge of having killed a man one never intended to kill, a man who left behind a young wife and child. When Emile learns that Benny Jr. wants to meet him, he’s “scared … He might swing at me.” Then Emile shudders as if Benny’s spectre swept through his body. “I hate to think about it,” he says.

But his conscience compels him to. The most compelling elements of Ring of Fire are the inner thoughts that petrify Emile’s face. He isn’t feigning remorse to inspire sympathy. Even in old age, his memories blotted by boxer’s dementia, unable to remember how his beloved mother died seven years earlier, he’s still a tortured man. He blames himself not out of self-loathing, but because he’s a rare person with a prodigious conscience and store of empathy.

When Emile and Benny Jr. finally meet, the raw pathos lies beyond comprehension. We glimpse genuine compassion and forgiveness, lending the human animal a touch of dignity. Here the documentary avoids becoming mawkish, but an even finer achievement is the way it weaves together fifty years of American cultural history through the struggles of one of its immigrants. With painstaking detail, the film reveals that for the purpose of mass entertainment, there are people who suffer more than we can imagine.

I'm not going to post any of the photos from the Griffith-Paret fight, they're too much. But in 2004, Emile Griffith met Benny "Kid" Paret's son, Benny Jr., in 2004. The meeting was arranged by friends and was part of a reconciliation and healing process for Griffith, who was still haunted by the fatal 1962 fight. The encounter was featured in the 2005 documentary film, Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story. This is photo of Emile Griffith (on the right) with Benny Paret's son, Benny Jr.

This is the book about Emile Griffith and the whole Benny Paret tragedy. It really is a heartbreaking story on so many levels, the tragedy of Paret's death, the struggle to be accepted for who you are, which continues to this day, it's a heavy story.

This is a great write-up about the tragedy of Griffith-Paret III bout and the moral complications of being a combat sports fan, a boxing fan, and the author of this article hits the nail on the head, as a boxing fan you do struggle and feel guilty about being a fan of a sport that can have fatal consequences.

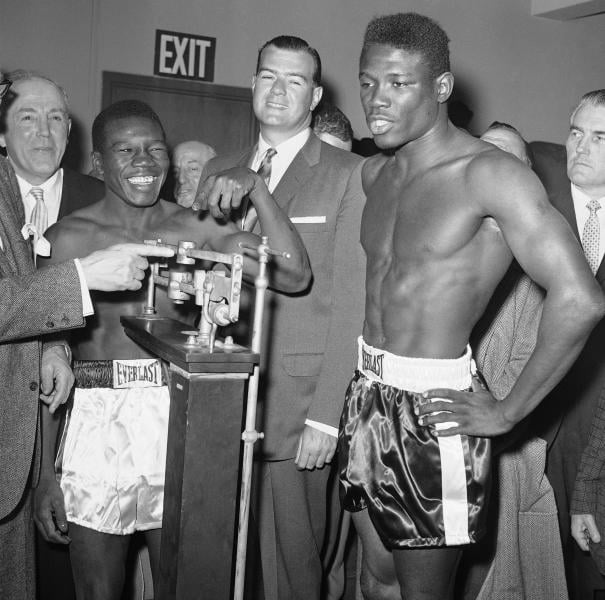

Emile Griffith (right) at the weight in with Benny Paret before the fight

THE FIGHT SITE

All is Fair in Love and War

By: Dan Albert

Doctrine on the Classics

Why do you watch combat sports?

Your answer might differ from my own, though my journey began with Marvelous Marvin Hagler’s eight-minute shootout with fellow generational great, Thomas Hearns. The battle was an absolute rollercoaster as Hagler became an embodiment of relentless pursuit under the barrage of returning gunfire. The carnage ended with him bloodied and unbowed over his barely-conscious rival. This was my first discovery of the classic bout - sometimes called a “war”. These sports had my attention, though it wasn’t what truly got me on board.

The fight that made me fall in love with combat sports was the five-round phonebooth brawl between Johny Hendricks and Robbie Lawler. In what remains among the most unique standup battles Mixed Martial Arts - let alone any pugilistic sport - has produced, the two southpaws engaged in a seemingly endless handfight with their respective games clashing. The absolute barnburner was decided by Hendricks’ attritional pace and sheer willpower. Hendricks was never my favorite fighter, but his final rally to slowly walk Lawler down through a mask of blood stands among the most awe-inspiring displays of will I’ve seen in a ring or cage.

I’d like to think that’s why we watch these contests. Competition often asks questions of its participants that other niche activities may not ask; competitors, therefore, are asked to demonstrate their mettle in front of a bitter, vindictive crowd of spectators. Combat sports, a niche that introduces spectators who lack that firsthand experience the competitors undergo, is primed to be especially unforgiving in its demand for mental fortitude. After all, what can be higher stakes for a payday or prize than the risk of hospitalization? Fighters differ from a majority of competitors because the risk associated with the demands is at an inherently greater rate.

Of course, anyone who watches combat sports understands that. It’s how they deal with that realization is what ultimately matters; moreover, everyone who steps into a ring deserves respect. For myself, recognizing that these men and women can do what a vast majority of people could never do is motivating and endearing. I have nothing but admiration for these contestants because, when it comes to having to draw a line, these fighters do their damndest to hold that line. To categorize these efforts as heroic is probably a bit too hyperbolic, though it’s, at the very least, a level close to it.

Stipe Miocic was never the most athletically-gifted nor necessarily favored to win many of his battles. He wasn’t thought of as the stereotypical baddest man on the planet. And yet, through nothing but sheer grit and determination, he became the most modest heavyweight great Mixed Martial Arts has ever produced. He didn’t compromise who he was as a person nor as a fighter - he held those lines in and out of the cage, even when beaten.

Three years ago, I saw Max Holloway and Dustin Poirier wage arguably the highest octane fight in the history of their sport. It was so vicious that I thought neither would be the same ever again. But it brought inspiration into my life from an unlikely source at a time where I desperately needed it.

Every year, I watch Joe Frazier push himself to the absolute limit to land his left hook to floor his archrival through a swollen visage; I consistently watch Archie Moore drag himself off the mat multiple times to finish Yvon Durelle several rounds past the point he should have been done; I see Thai greats and rivals Samson Issan and Lahkin Wassandasit build upon their previous battle and drag the other into deeper levels.

All of these are wars. They embody fighters at their strongest in a mutual battle of wills. These fights bring personal introspection and, in my opinion, reveal the values of the spectator who watches their respective sport just as much as it may reveal who the fighter is. There’s something forthright about that. Fighting isn’t and cannot be for everyone; for those who do watch it, it’s essential to remember what happened. What did these fighters - still these everyday figures - sacrifice in that arena? How can you offer that the veneration it deserves?

I know many who emphasize how brutal some battles are and that they would prefer to not watch them. I don’t think I can ever judge anyone for feeling how they do, but I would urge them to never mischaracterize a bout because of how they feel. A war was a war; people took physical damage in that ring. To deny that means you are not taking responsibility as an audience member. I understand that statement is combative, though I stand by it. Fighters are willing to put so much on the line; ergo, we have to respect what they do. And, as far as I’m concerned, being respectful means being objective about what happened. A war was a war, period.

There’s a greater problem whereupon many audience members are liable to objectify fighters as these ephemeral larger-than-life warriors. It’s easy to see why. On one hand, audience members are their own partakers as observers. There’s an associative guilt with watching pugilists mash one another into bruised, blood-soaked caricatures just as much as there is a sense of wonder. For many, it’s probably easier to just go, “This is Awesome,” and continue along. I think this ignores the aforementioned responsibilities. Sure, wars are incredible to watch and leave a surrealist high as a viewer. But they are still wars. Nobody is going to not watch Mike Zambidis and Chahid Oulad El Hadj reincarnate themselves into the embodiment of rock’em sock’em robots and not be yelling like Michael Schiavello was until their voice was a hoarse remnant. What I’ve been trying to argue is that there’s a balance here.

You can still see these fighters as extraordinary without fetishizing them into nonhuman marionettes you would bang together to produce clang noises like a prepubescent child. These fighters aren’t toys and aren’t obligated nor deserve to be treated as such. They are human beings. You can admire them without dehumanizing them.

To acknowledge that there is a degree of guilt just as much as there is a fascination is what I believe every fan needs to do.

And then you run into the challenge whereupon there’s so much guilt that you don’t want to watch a fight ever again.

The Components of a Fight

One of my activities as a combat sports scholar is to find classics and catalogue them. Again, if I’m to appreciate what fighters have done, then remembering and commemorating what did happen seems vital - and, genuinely, it’s just fun to watch different stylistic clashes.

I tend to believe a fight is made of up of three components:

1) The fight itself. Akin to how a book or movie has its narrative, a fight has its own structure. Round-after-round, minute-by-minute, action-by-action - all segmented pieces that combine all the parts of the fight - topped off by the interactions between corners and officials. This can be called “the what”.

2) The outcome. Ultimately, the fireworks stop going off and you’re left with the aftermath. A friend maybe looks over to you and asks, “Well, what did you think?” The end of a fight has something similar to that.

Someone has been knocked out. Maybe they or their corner threw in the towel. Did the doctor stop it all on a cut? What if both ran out of time and both have to stand their ground, arms at their side, asking themselves if they did just enough to impress a few nearby onlookers. The judges and their decisions, based upon majority rules, lead to a plethora of responses. Satisfactory roars to mass condemnation; all eyes and voices directed at the two persons who just wanted to get their hand-raised.

3) The connective tissue.

Most of us on this site think about fights more than the sheer number we watch. Every fight offers a valuable lesson beyond some fulfillment of spectator catharsis. It isn’t simply an emotional sort of response either; you don’t just have to be inspired. You might have learned something new about the fighter in the same vein as they learned something about themselves.

Charles Oliveira fought Michael Chandler for the UFC’s vacant 155lbs-belt only a month ago. He has to survive a moment of danger and come back to finish Chandler in a shootout. For years, Oliveira had struggled to get to the top and faced doubt from so many sources along the way. It isn’t just that he beat Chandler that was important, it’s how he beat him that mattered.

“Michael said I couldn’t take pressure. And he hit, and hit, and hit. And I’m still here.”

— Charles Oliveira, UFC 262

Maybe, just maybe, Oliveira didn’t know if he could gut out a moment in the biggest spotlight. Maybe afterwards, he didn’t know how he did. But what matters is that he fucking did. When Chandler attempted to flurry, Oliveira smothered and defended himself until the bell. He learned his lesson: Don’t let Chandler get a moment again. And he delivered on that self-promise the very next round. In totality, he demonstrated his technical growth and maturation as a fighter.

A fight and its outcome are inherently interconnected. What happens in said fight is a driving process towards an inevitable outcome. At the end of the day, no fighter nor the spectator audience can entirely separate the two. Recognizing the strengths and interplay between them, however, is essential as an audience member, I feel.

I may not agree with the judges giving an unpopular decision to Srisket Sor Rungvisai versus Roman Gonzalez, though I cannot take away either man giving practically every ounce of themselves in the ring. Even if you think the wrong man won, you cannot deny the bout was sensational and not be proud of what the Thai accomplished.