"PROOF" first used by Mint in 1834 describing King of Siam and Sultan of Muscat Presentation Sets

When did the U.S Mint start minting Proof Coins? When did they start calling them Proof Coins? The term "Proof" was not a widely used term at the U.S. Mint until the 1850's. But the first use of the term in Mint documents is found in a Letter Register of the U.S. Mint in 1834.

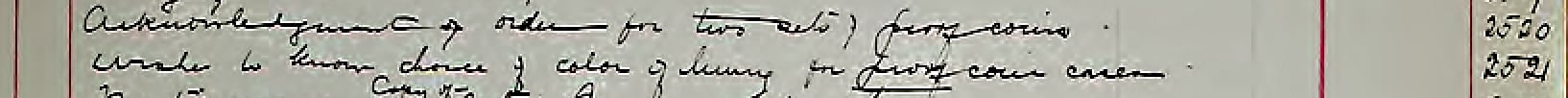

Secretary of State John Forsyth sent a letter to Mint Director Samuel Moore on November 11, 1834 ordering presentation sets to be made for foreign dignitaries that are now known as the King of Siam and Sultan of Muscat presentation sets. The actual letter asks for "specimen" coins to be made. Moore acknowledged the letter the same day, and his response was recorded in the Letter Register as "Acknowledgement of order for two sets of proof coins."

The next entry in the Register records Moore's letter to Forsyth on November 29th that "Wishes to know choice of color of lining for proof coin cases."

Denga speculates that Franklin Peale brought this term back from his trip to Europe, and the entries in this register were made by someone in 1835 after Peale's return. As far as I know, there is no further use at the Mint of the term "Proof" until the 1850's.

Mint documents supplied by RWB.

Comments

Cool. I had thought the term first showed up in the mid-1850s.

Julian is somewhat misdecribing what I had written in the past regarding Peale’s report and what John Dannreuther and I presented in his proof book.

In the late 1980’s, I had NARA photocopy the intire “Peale file,” including the Peale report (now on NNP), and began searching thru it for minting technology info. On page 42 of the report, under the section describing the rules, regulations,and procedures for awarding design contracts to engravers by the French Commission, Peale noted that “They take proofs of these Dyes, and exhibit both to the Public in the Minetary Museum.”

I wrote some articles on the report in the early 1990’s and this specific section is also reproduced in Dannreuther’s proof book, Vol IV, Part One, page 70 - 71.

While it may sound like Peale is using the term in the modern sense, you really need to read the prior 13 pages or his report, starting on page 27, to fully understand the context. And that context IS NOT the context used for the term “proof” today or in 1859 (more in a bit).

Four sake of brevity, I’ll sumarize the rules and requirements a bit (those who want to read them fully can access the report on NNP). The description of the French Mint begins on page 27. You do need to read it fully thru page 42 for a complete understanding.

Designs for French coinage and medals were decided by an official competition open to all. An engraver need merely submit a design within specification, including working dies and hubs, to the Commission, Designs for the obverse and reverse were considered separately. “Proofs” (e.g., uniface die trials) of each die were produced and they were displayed and judged per the rules and regulations described.

Thus,, the term “proof” to Peale (and most likely others in the US and Europe at this time) did not mean a special coin produced for collectors or to show off capabilities or the complete design, but rather in the sense of a printer’s proof (from which the term likely derived), it was an example of the proposed design which, in the case of coins and medals, included an obverse and reverse.

So then, what do we make of the entries in th “Letter Regirster”? Without seeing the original letters, NOTHING. We do not know when and under what circumstances those registers were created and thus they can mean nothing in terms of determining when the word “proof” first comes into use.

When is the first documented use of “proof” in the current context? As Danruether notes on page 42 of the aforementioned book, the first such usage is by Director James Ross Snowden in late 1859. Neither JD nor I have found and earlier usage of the term in the modern context.

However, it is clear from Snowden’s notation that, by the time, the term had become synoymous with Master Coin. Exactly when this occurred is unknown. Earlier letters, and some later, from mint officials, such as Dubois, continued to use the oldd term of Master Coin. Thus, the 1850’s appear to be the genesis of the term in the modern context.

That is what is currently known. I would not be surprised if the teens came into use in the 1840’s after Peale’s return in June 1835.

@Ronyahski Thank you for this information.

Curiously, I wanted see how that word evolved from then to now. To stay fairly consistant I stayed with the same type (i.e. Webster). The definitions below are from Webster’s 1828 versus the latest Merriam-Webster dictionary (both online).

Webster’s 1828:

PROOF,noun

Trial; essay; experiment; any effort, process or operation that ascertains truth or fact. Thus the quality of spirit is ascertained by proof; the strength of gun-powder, of fire arms and of cannon is determined by proof; the correctness of operations in arithmetic is ascertained by proof

In law and logic, that degree of evidence which convinces the mind of the certainty of truth of fact, and produces belief. proof is derived from personal knowledge, or from the testimony of others, or from conclusive reasoning. proof differs from demonstration, which is applicable only to those truths of which the contrary is inconceivable.

This has neither evidence of truth, nor proof sufficient to give it warrant.

See arms of proof

Firmness of mind; stability not to be shaken; as a mind or virtue that is proof against the arts of seduction and the assaults of temptation.

The proof of spirits consists in little bubbles which appear on the top of the liquor after agitation, called the bead, and by the French, chapelet. Hence,

The degree of strength in spirit; as high proof; first proof; second, third or fourth proof

In printing and engraving, a rough impression of a sheet, taken for correction; plural proofs, not proves.

Armor sufficiently firm to resist impression. [Not used.]

PROOF is used elliptically for of proof

I have found thee

PROOF against all temptation.

It is sometimes followed by to, more generally by against.

——-

Merriam-Webster:

1a : the cogency of evidence that compels acceptance by the mind of a truth or a fact

b : the process or an instance of establishing the validity of a statement especially by derivation from other statements in accordance with principles of reasoning

2 obsolete : EXPERIENCE

3 : something that induces certainty or establishes validity

4 archaic : the quality or state of having been tested or tried

especially : unyielding hardness

5 : evidence operating to determine the finding or judgment of a tribunal

6a plural proofs or proof : a copy (as of typeset text) made for examination or correction

b : a test impression of an engraving, etching, or lithograph

c : a coin that is struck from a highly polished die on a polished planchet, is not intended for circulation, and sometimes differs in metallic content from coins of identical design struck for circulation

d : a test photographic print made from a negative

7 : a test applied to articles or substances to determine whether they are of standard or satisfactory quality

8a : the minimum alcoholic strength of proof spirit

b : strength with reference to the standard for proof spirit

specifically : alcoholic strength indicated by a number that is twice the percent by volume of alcohol present

whiskey of 90 proof is 45 percent alcohol

Just as an aside, I have sometimes wondered why the "proof" of an alcoholic spirit is measured on a scale of 1-200, where 140 proof would be 70% pure alcohol.

There was a lot of cross-over between printing and minting technology. Printers' proofs were well known and likely influenced terminology for analogous processes in stamping coins. Adam Eckfeldt refers to "Master coins" and other contemporary documents sometimes use the word "proof" although rarely with any clear, consistent meaning. Likewise the term "specimen" had meanings that varied with context and general subject. By the 1850s clerks were equating "specimen" with what the Coiner called "experimental pieces" and what we call "pattern pieces." But --- not always.

Collector writings of the earlier 19th century often use "specimen" to imply a "master coin" OR any new coin selected for them. "Specimens" of United States coinage were sent to several countries in exchange programs and there are usually called "master coins" by the Mint and "specimens" by the State Department.

Given the range of uses of multiple terminologies, we have to be very careful about calling that critter in the yard a rabbit or a cat -- with out the skin and head, they are almost identical.

It had to do with the test to determine alcohol content. See wikipedia.

As Roger pointed out, there was a gradual evolution of the term for a coin specially struck for presentation or collectors. The US Mint used "specimen" into the 1850's. However, they also used "master coin." The first official use of "master coin" that I've found so far is in William Dubois' 1843 letter to Matthew Stickney.

The first official use of "proof" was in Feb 1860 by Snowden. However, the term was in common use by collectors at least by the mid-1850's as auction catalogs of the period commonly used it for British coins. The first use of "proof" for US coins was in the 1855 Kline sale.

Then there's the wonderfully obtuse term "semi-proof," first used by Pollock and Linderman for some presentation Trade Dollars in April 1874. Dannreuther and I published an article on these pieces in the Gobrecht Journal some time ago. They were made using polished working dies and polished planchets, but they don't have the frost of proof dies.

There are quite a few minor coins from the 1860's on that also meet this criteria. The possibility of a book on these pieces is currently being discussed. It would certainly open up a new collecting genre and offer collectors the opportunity for some neat finds.

Roger, do you have any insight as to when the Register of the 1834 letters was created? Do the 2520 and 2521 numbers associated with these letters offer any clues?

About all we know is that it post dated the letters and is likely from a period when the clerks were reorganizing and cross referencing old correspondence. There are also fair copy journals containing copies of old correspondence some of which date from the mid-1890s per existing letters of instruction. A very few of the compilations are signed by the clerk making copies or assembling the volumes. Further all of the original correspondence volumes were assembled at a later date. From the condition of bindings, paper aging, etc., my estimate is that many were assembled in the 1850s and then again in the 1870s - but those are just guesses.

Here is the inside volume label for the correspondence register Ronyahski mentioned, and a sample double page. The volume is available for download in PDF from NNP.

RE: "Do the 2520 and 2521 numbers associated with these letters offer any clues?"

The numbers are consecutive. They might once have related to the location of original letters, but we can't be certain that is correct.

Note on above: The original journal is approximately 14x20-inches. Each letter description flows across two facing sheets. Each page was photographed individually. The sample posted was assembled by compositing facing pages into one image. (The overlap can be seen to right of the gutter.)

Considering that the information about the use of “proof” was first published

in this forum on June 14, 2014. I suggest Rittenhouse read that posting before

commenting on the matter. I was not misdescribing what he wrote since I was

not using his material for reference.

It is worth noting that Peale also visited London in November 1833 and likely

heard the “proof” term while at the Royal Mint.

Taking into consideration the methods used to record letters under later directors

there is little doubt that the register of letters in question was completed in late

1835 or early 1836. The use of “proof” is therefore official for internal use at this

time but the public use is another matter.

Having read several articles on 'proof', it's origin etc., I think it is foolish to continue it's use in relation to alcohol....However, I am content with the modern application of 'proof' to coins.... It is interesting to review the origins of the term, but to me, now and for the rest of my collecting days, proof, in regards to coins, will mean a coin from highly refined dies, struck multiple times, resulting in a beautiful rendition of a coin. That works for me.... Cheers, RickO

Cheers, RickO

Just a thought, but maybe a slightly different definition will work:

A coin produced with detail as close as possible to the original dies; usually with mirror-iike polished fields.

This avoids the difficulties with:

a coin from highly refined dies - nothing unusual about "proof" dies except the polishing.

struck multiple times - now, but not always.

resulting in a beautiful rendition of a coin - "beautiful" is subjective; some designs are ugly no matter what is done to them.

Pretty close to the criteria Dannreuther and I use for 19th and most 20ty century:

A coin specially struck on a screw or hydraulic press using polished dies and a polished planchet resulting in a coin with “watery” mirror fields looking like a thin sheet of water on a mirror, the rims will typically be broad and flat, and the lettering and numerals will be “squared-off” to the field as a result of the extra striking pressure. Plain edge pieces are struck using polished collars. May or may not have frosted devices.

Looks good, although the watery part is too subjective for me -- it's also an artifact of manual polishing rather than machine work.

Most things have a "what it is" and a "what it looks like" description.