Civil War 150 year anniversary post

DCW

Posts: 7,646 ✭✭✭✭✭

DCW

Posts: 7,646 ✭✭✭✭✭

150 years ago today, on April 9, 1865, Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse. Post a civil war token, medal or US coin in tribute to those tumultuous years of 1861-1865.

Dead Cat Waltz Exonumia

"Coin collecting for outcasts..."

0

Comments

J. Doyle Dewitt in 1959 stated this medal was made and distributed during McClellan's 1864 Presidential Campaign which is not the case. Joseph H. Merriam struck a series of "Civil War Union General" medals in 1863 which also included Major General Philip Kearney and Major General Joseph Hooker featuring the similar obverse die design and the exact reverse die. David E. Schenkman considered it "Rare" in his 1980 article on Boston medalist Joseph H. Merriam which featured plated examples of all Merriam's works however even with all his connections was unable to locate an example to provide plated photographs of this McClellan.

1864 Major General George B. McClellan Presidential Campaign, Dewitt GMcC-1864-10, 32mm Diameter, White Metal, Struck by William Key.

Obverse: McClellan & Pendleton Democratic Candidates / Reverse: The Constitution As It Is The Hope Of The Union.

The obverse die crack occurred during early stage and is common on all and stretches rim to rim directly through the bust of McClellan.

1864 Major General George B. McClellan Presidential Campaign, Copper, 34mm Diameter, Dies prepared by George H. Lovett of New York

Looking for Top Pop Mercury Dime Varieties & High Grade Mercury Dime Toners.

Pratt Street Riot: A first-hand account from the memoir of Mayor George W. Brown who recalls the first bloodshed of the Civil War.

The battle at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, launched the Civil War. But the divided nation didn’t suffer its first causalities until a week later, hundreds of miles to the north in Baltimore, Md.

The 6th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry and Pennsylvania troops had arrived at Baltimore’s President Street Station on April 19th, unaware that their mission – to head to Washington, D.C., to defend the capital at the request of President Lincoln – would be marred by the first bloodshed of the Civil War.

As the 1,700 troops made their way down Pratt Street to board a southbound train at Camden Yards, they were attacked by several thousand Confederate sympathizers, resulting in the death of 21 soldiers and citizens and injuring more than 100 people.

On the morning of the 19th of April I was at my law office in Saint Paul street after ten o’clock, when three members of the city council came to me with a message from Marshal Kane, informing me that he had just received intelligence that troops were about to arrive – I did not learn how many – and that he apprehended a disturbance, and requested me to go to the Camden-street station. I immediately hastened to the office of the board of police, and found that they had received a similar notice. The Counsellor of the City, Mr. George M. Gill, and myself then drove rapidly in a carriage to the Camden-street station. The police commissioners followed, and, on reaching the station, we found Marshal Kane on the ground and the police coming in in squads. A large and angry crowd had assembled, but were restrained by the police from committing any serious breach of the peace.

After considerable delay seven of the eleven companies of the Massachusetts regiment arrived at the station, as already mentioned, and I saw that the windows of the last car were badly broken. No one to whom I applied could inform me whether more troops were expected or not. At this time an alarm was given that the mob was about to tear up the rails in advance of the train on the Washington road, and Marshal Kane ordered some of his men to go out the road as far as necessary to protect the track. Soon afterward, and when I was about to leave the Camden-street station, supposing all danger to be over, news was brought to Police Commissioner Davis and myself, who were standing together, that some troops had been left behind, and that the mob was tearing up the track on Pratt street, so as to obstruct the progress of the cars, which were coming to the Camden-street station. Mr. Davis immediately ran to summon the marshal, who was at the station with a body of police, to be sent to the point of danger, while I hastened alone in the same direction. On arriving at about Smith’s Wharf, foot of Gay street, I found that anchors had been placed on the track, and that Sergeant McComas and four policemen who were with him were not allowed by a group of rioters to remove the obstruction. I at once ordered the anchors to be removed, and my authority was not resisted. I hurried on, and, approaching Pratt-street bridge, I saw a battalion, which proved to be four companies of the Massachusetts regiment which had cross the bridge, coming towards me in double-quick time.

They were firing wildly, sometimes backward, over their shoulders. So rapid was the march that they could not stop to take aim. The mob, which was not very large, as it seemed to me, was pursuing with shouts and stones, and, I think, an occasional pistol-shot. The uproar was furious. I ran at once to the head of the column, some persons in the crowd shouting, “Here comes the mayor.” I shook hands with the officer in command, Captain Follansbee, saying as I did so, “I am the mayor of Baltimore.” The captain greeted me cordially. I at once objected to the double-quick, which was immediately stopped. I placed myself by his side, and marched with him. He said, “We have been attacked without provocation,” or words to that effect. I replied, “You must defend yourselves.” I expected that he would face his men to the rear, and, after giving warning, would fire if necessary. But I said no more, for immediately felt that, as mayor of the city, it was not my province to volunteer such advice. Once before in my life I had taken part in opposing a formidable riot, and had learned by experience that the safety and most humane manner of quelling a mob is to meet it at the beginning with armed resistance.

The column continued to march. There was neither concert of action nor organization among the rioters. They were armed only with such stones or missiles as they could pick up, and a few pistols. My presence for the short time had some effect, but very soon the attack was renewed with great violence.

The mob grew bolder. Stones flew thick and fast. Rioters rushed at the soldiers and attempted to snatch their muskets, and at least on two occasions succeeded. With one of these muskets a solider was killed. Men fell on both sides. A young lawyer, then and now known as a quiet citizen, seized a flag of one of the companies and nearly tore it from its staff. He was shot through the thigh and was carried home apparently a dying man, but he survived to enter the army of the Confederacy, where he rose to the rank of captain, and he afterward returned to Baltimore where he still lives. The soldiers fired at will. There was no firing by platoons, and I heard no order given to fire. I remember that at the corner of South street several citizens standing in a group fell, either killed or wounded. It was impossible for the troops to discriminate between rioters and by-standers, but the latter seemed to suffer most, because, as the main attack from the mob pursuing the solders from the rear, they, in their march, could not easily face backward to fire, but could shoot at those whom they passed on the street. Near the corner of Light street a soldier was severely wounded, who afterward died, and a boy on a vessel lying in the dock was killed, and about the same place three soldiers at the head of the column leveled their muskets and fired into a group standing on the sidewalk, who, as far as I could see, were taking no active part. The shots took effect, but I cannot say how many fell. I cried out, waving my umbrella to emphasize my words, “For God’s sake don’t shoot!” but it was too late. The statement that I begged Captain Follansbee not to let the men fire is incorrect, although on this occasion I did say, “Don’t shoot.” It then seemed to me that I was in the wrong place, for my presence did not avail to protect either the soldiers or the citizens, and I stepped out from the column… At the moment when I returned to the street, Marshal Kane, with about fifty policemen (as I then supposed, but I have since ascertained that in fact there were not so many), came at a run from the direction of the Camden-street station, and throwing themselves in the rear of the troops, they formed a line in front of the mob, and with drawn revolvers kept it back. This was between Light and Charles streets. Marshal Kane’s voice shouted, “Keep back, men, or I shoot!” This movement, which I saw myself, was gallantly executed, and was perfectly successful. The mob recoiled like water from a rock.

Four of the Massachusetts regiment were killed and thirty-six wounded. Twelve citizens were killed, including Mr. Davis. The number of wounded among the latter has never been ascertained. As the fighting was at close quarters, the small number of casualties shows that it was not so severe as has generally been supposed.

This is the medal in copper of the massive gold medal than Congress awarded to Grant for his victory at Vicksburg on July 4, 1863.

Here the Smithsonian photo of the gold medal that was awarded to Grant with the box of issue which is made of ebony and gold. This medal contains over 2 Troy pounds of solid gold.

This is the rejected design for a medal that was authorized by the Swiss - American Republicans. There are said to be 10 or fewer examples of this medal known.

I've never owned such a tangible piece of history. If it could speak, oh the story it might tell! It was clearly worn and carried as a pocket piece long after its use during the war, probably by the proud veteran himself.

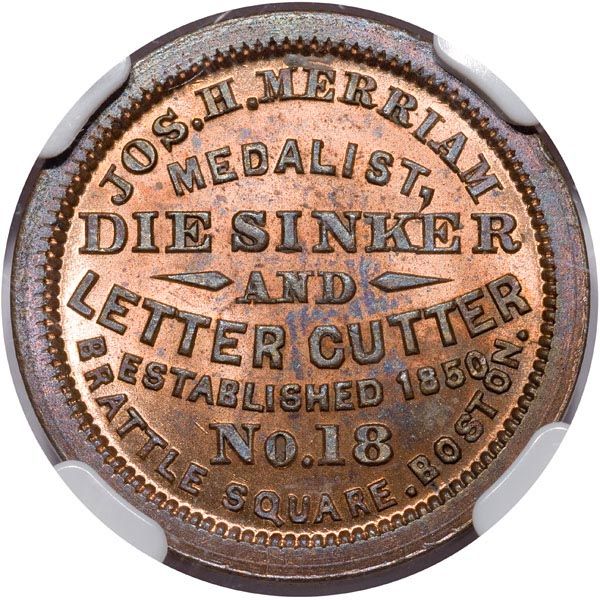

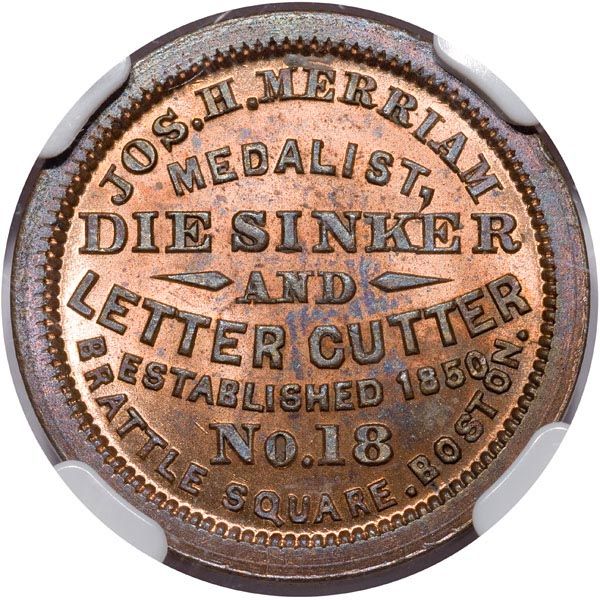

These "dog tags" were issued by Boston diesinker Joseph H. Merriam, bringing peace of mind that the soldier's remains might be identified if he were disfigured on the battlefield. These were purchased by soldiers from many different northern states, but it is nice to own one from Massachusetts given the connection to Merriam. They were often stamped with the battles of which the soldier participated.

Instead of the usual "War of 1861" stamp, this one simply reads "Bull Run."

Dead Cat Waltz Exonumia

"Coin collecting for outcasts..."

Dead Cat Waltz Exonumia

"Coin collecting for outcasts..."

Oh well. The more the merrier.

.

CoinsAreFun Toned Silver Eagle Proof Album

.

Gallery Mint Museum, Ron Landis& Joe Rust, The beginnings of the Golden Dollar

.

More CoinsAreFun Pictorials NGC

Dead Cat Waltz Exonumia

"Coin collecting for outcasts..."

Successful BST deals with mustangt and jesbroken. Now EVERYTHING is for sale.