Johnny Kilbane actually a few statues honoring him, one in his native Ireland and one display in Cleveland Ohio. This is the one on Achill Island in Mayo Ireland.

Tony Zale, the "Man of Steel" floors Rocky Graziano, "The Rock", during one of the fights in their trilogy. Their rivalry was one of the most violent in boxing history, each of their three fights was a life-and-death struggle that ended with a brutal knockout.

This is one of the most beautiful knockouts you'll ever see, Tony Zale-Rocky Graziano III. Watch Zale land a shot to the body of Graziano and then finish him with a left hook. Just a thing of beauty.

Tony Zale was one of the greatest body punchers in boxing history, he really knew how to tear your body up. Years after their trilogy, Rocky Graziano said he still had nightmares about Zale punching his body. The great Billy Soose, who fought Zale, once said about being punched in the body by Tony Zale, "When he hits you in the belly, it's like someone stuck a hot poker in you and left it there."

Battling Siki was the first African born boxing world champion, born in French-Senegal. He won the world light heavyweight championship after knocking out Georges Carpentier in 1922, one of the most bizarre fights in boxing history. It was supposed to have been a fix, Carpentier was supposed to go easy on Siki and Siki was supposed to lose, but Siki became enraged after Carpentier began pouring it on him. What transpired in this fight was chaos and has become part of boxing lore.

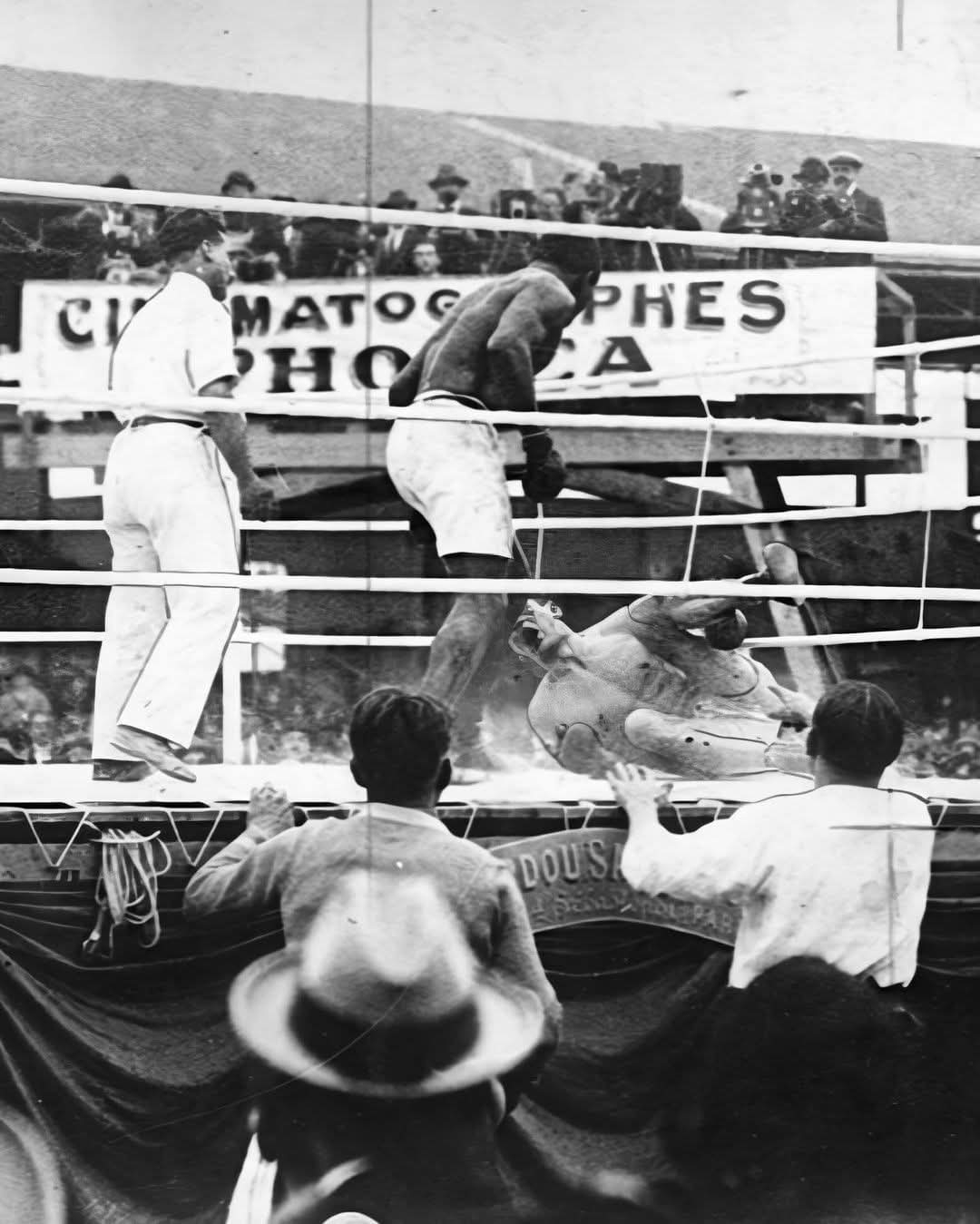

Battling Siki stands over a bloody Georges Carpentier during their infamous encounter

The Fight that Wouldn’t Stay Fixed

How an apparent misunderstanding led to a brawl that turned into a donnybrook that became a legend

Despite the promoters’ best efforts, the 1922 light-heavyweight fight between the popular European champion Georges Carpentier and an obscure Senegalese brawler named Amadou Mbarick Fall, better known as “Battling Siki,” wasn’t supposed to be much of a fight. In the run-up to the September 22 event, newspapers confidently reported that fight fans could “expect to see the French idol win inside of six rounds.”

And yet more than 50,000 Parisians flocked to the Buffalo Velodrome in France, creating the first “million-franc” boxing match. Carpentier was a war hero beloved by his countrymen, and even though he had a lackluster record, Battling Siki was more than willing to help stir up interest in the fight. He was billed as the “Jungle Hercules,” and reporters described him as a man who fought “like a leopard,” with “great muscles” rippling under his dark skin and “perfect white teeth so typical of the negroid.” Siki had taken a hit on the head with a hammer, one paper stated, “and scarcely felt it.”

Even Siki’s own manager, Charlie Hellers was quick to point out the fighter’s “gorilla’s skill and manners” to reporters. “He’s a scientific ape,” Hellers said. “Just imagine an ape that has learned to box and you have Battling Siki.”

For his part, Siki told reporters that he was going to knock Carpentier out in the first round because he had plans to fight the world heavyweight champion next. “Tell Jack Dempsey he’s my next meat,” Siki was quoted as saying.

In truth, the fighter was born and raised in the Senegalese city of Saint-Louis and moved to France as a teen. “I have never even seen a jungle,” he would say later. He was often spotted around Paris dressed in expensive suits and fancy hats, sometimes with his pet monkey perched on his shoulder. His training, it was said, consisted of “caviar and cognac,” and he preferred doing his “roadwork on a dance floor.”

On the afternoon of September 22, fight fans packed the velodrome to see Carpentier defend his title. Nicknamed the “Orchid Man” for the corsages he often wore with his tailored suits, Carpentier had been fighting professionally since he was 14. Although he was coming off a failed attempt to win Dempsey’s heavyweight title, he’d helped secure boxing’s first million-dollar gate. Fighting again as a light-heavyweight, the Frenchman’s future was still bright—so bright that Carpentier’s handlers were taking no chances. They offered Battling Siki a bribe to throw the fight. Siki agreed, under the condition that he “didn’t want to get hurt.” What followed was one of the strangest bouts in boxing history.

Although Siki later admitted that the fight was rigged, there’s some question as to whether Carpentier knew it. Early in the first of 20 scheduled rounds, Siki dropped to a knee after Carpentier grazed him, and then rose and began to throw wild, showy punches with little behind them. In the third, Carpentier landed a powerful blow, and Siki went down again; when he got back on his feet, he lunged at his opponent head first, hands low, as if inviting Carpentier to hit him again. Carpentier obliged, sending Siki to the canvas once more.

At that point, the action in the ring turned serious. Siki later told a friend that during the fight, he had reminded Carpentier, “You aren’t supposed to hit me,” but the Frenchman “kept doing it. He thought he could beat me without our deal, and he kept on hitting me.”

Suddenly, Battling Siki’s punches had a lot more power to them. He pounded away at Carpentier in the fourth round, then dropped him with a vicious combination and stood menacingly over him. Through the fourth and into the fifth, the fighters stood head to head, trading punches, but it was clear that Siki was getting the better of the champion. Frustrated, Carpentier charged in and head-butted Siki, knocking him to the floor. Rising to his feet, Siki tried to protest to the referee, but Carpentier charged again, backing him into a corner. The Frenchman slipped and fell to the canvas—and Siki, seemingly confused, helped him get to his feet. Seeing Siki’s guard down, Carpentier showed his gratitude by launching a hard left hook to Siki’s head just before the bell ended the round. The Senegalese tried to follow Carpentier back to his corner, but handlers pulled him back onto his stool.

At the start of round six, Battling Siki pounced. Furious, he spun Carpentier around and delivered an illegal knee to his midsection, which dropped the Frenchman for good. Enraged, Siki stood above him and shouted down at his fallen foe. With his right eye swollen shut and his nose broken, the Orchid Man was splayed awkwardly on his side, his left leg resting on the lower rope.

Siki returned to his corner. His manager, Charlie Hellers, blurted out, “My God. What have you done?”

“He hit me,” Siki answered.

Referee M. Henri Bernstein didn’t even bother counting. Believed by some to be in on the fix, Bernstein tried to explain that he was disqualifying Siki for fouling Carpentier, who was then being carried to his corner. Upon hearing of the disqualification, the crowd unleashed a “great chorus of hoots and jeers and even threaten the referee with bodily harm.” Carpentier, they believed, had been “beaten squarely by a better man.”

Amid the pandemonium, the judges quickly conferred, and an hour later, reversed the disqualification. Battling Siki was the new champion.

Siki was embraced, just as Carpentier had been, and he quickly became the toast of Paris. He was a late-night fixture in bars around the city, surrounded by women, and he could often be seen walking the Champs-Elysees in a top hat and tuxedo, with a pet lion cub on a leash.

Carpentier fought for a few more years but never never reclaimed his title. Retiring from the ring, he toured the vaudeville circuits of the United States and England as a song-and-dance man. Battling Siki turned down several big fights in the United States to face Mike McTigue in Ireland. That the bout was held on St. Patrick’s Day in Dublin was likely a factor in Siki’s losing a controversial decision. He moved to New York City in 1923 and began a downward spiral of alcohol abuse that led to countless confrontations with the police. By 1925, he was regularly sleeping in jail cells after being picked up for public intoxication, fighting and skipping out on bar debts.

In the early hours of December 15, 1925, Amadou Mbarick Fall, aka "Battling Siki", was wandering through the Hell’s Kitchen section of New York’s West Side when he took two bullets in his back and died on the street. Just 28 years old, Siki was believed to have been killed over some unpaid debts, but the homicide remains unsolved. Adam Clayton Powell presided over Siki’s funeral in Harlem, and in 1991, the pugilist’s remains were brought back to Senegal.

Battling Siki wasn't very skilled but he was a very tough and wild brawler with brutal power in his punches. He was savage not just in the ring, but as a person, he drank a lot, he even drank before fights, and could be very mentally unstable. He was a handful for anyone that stepped in the ring with him.

Battling Siki vs "Bold" Mike McTigue was one for the books, McTigue was a clever scientific Irish light heavyweight boxer. This fight took place in Dublin Ireland in 1923, and at the time there was a civil war raging in Ireland, you could actually hear machine gun fire in the streets and the police presence was heavy due to a bomb threat, and one exploded near the venue as the boxers were entering the ring. Two children were injured and nearby windows were blown out by the blast. Mike McTigue won the title in a 20-round points decision, making him the first Irishman to win a world title on Irish soil. It was a very controversial fight, with some thinking Siki should have won. A lot of people think that McTigue got the decision because of home cooking. I've seen footage of the fight and from what I've seen I think McTigue rightfully got the decision, he boxed very cleverly, but McTigue did have his hands full with Siki, he had one hell of a time trying to deal with Siki's wild and vicious attacks.

Battling Siki is one of the most fascinating fighters you'll ever read about. He had a wild life.

Battling Siki: One of Boxing’s Most Interesting Stories

By Travis “Novel” Fleming

Former 1920’s light heavyweight champion Battling Siki, 60-24-4, 31 KO’s, has always been a fighter that piqued my interest. By all accounts, he was one of the most flamboyant, strange, unique, and heroic, characters in the history of boxing. His story is a true rags to riches tale, against all odds. His meteoric rise to the top of the boxing world came just as quickly as his tragic fall and unsolved murder.

The first time I heard about Siki was in an excellent book about tragic boxing stories. I wish I could remember the book’s name or author as it would have been a great point of reference for this article. Anyways, moving along, the book had chapters devoted to various boxers whose careers or lives ended in tragedy, and there was a chapter all about Battling Siki that reeled me in. I checked the book out of my local library as a youngin, and, like anyone in my generation of low attention spans, I immediately went to the middle of the book to flip through the glossy picture section where I was instantly drawn to a dapper young black man in a top hat that was sporting a tuxedo, an opera cape, and a monacle, while holding the leash of a giant lion, which stood by his side.

The caption mentioned something along the lines of “Former light heavyweight champion Battlin Siki walking his pet lion in the streets of Paris.” This was enough to convince me that the chapter on Siki should be my starting point. I was fascinated by his rise from poverty in his native Senegal, to his heroics in World War 1, to his light heavyweight championship winning effort, but most of all it was the stories about his crazy lifestyle outside of the ring that stuck with me to this day. From his flashy dressing, heavy drinking, love of absinthe, and his run ins with the law, to his pet lion that he would walk around major cities with while shooting his gun in the air in case people weren’t already paying undivided attention to the flashy black man with the giant beast.

The story of Battling Siki never fails to stick out to me as one of the most interesting in the history of boxing, so I figured I’d do my best to enlighten those who have yet to hear about this interesting character. This is by no means a complete biography, and there are many conflicting reports on Siki’s life, behavior, and in ring accomplishments. This article’s purpose is just to shed some light on one of boxing’s most unique champions for those who haven’t heard of his exploits. Those that have read up on Siki will likely be familiar with everything mentioned in my shoddy short summary of his tale.

Battling Siki was born in the late 1800’s in the French colony of Senegal, Africa. His family was very poor and times were tough, as they were for the vast majority of his countrymen. At just eight years old in his hometown of Saint Louis, while partaking in his hobby of watching the port city’s harbour traffic, a rich German dancer got off a ship that was en route to Marseilles, France, and asked the young Siki, at the time known by his birth name Baye Phal, or Amadou M’Barick Fall, if he could show her around the city. Siki obliged, and the dancer took quite a liking to him. The lady’s name was Mme Farquenberg and she asked the young Baye Phal if he would like to accompany her to France where she would assure he’d be taken good care of.

The ship was departing shortly after her proposition, and fearing she might change her mind, Baye Phal agreed to join her and left for France without even being able to notify his family that he may never see them again. In France, the lady taught him how to read and write, bought him nice clothes, and made sure his belly was full. Eventually, the dancer had to go to Germany but couldn’t take Phal with her without a passport, so she left him in Marseilles with enough money to take care of himself. Throughout the remainder of his life, he would attempt to write to Mme Farquenberg but was sadly never able to locate the lady who was so kind to the young Senegalese.

On his own in Marseilles, often working as a dishwasher among other menial jobs, he met Paul Latil, a boxing instructor who taught him how to crouch and deliver a proper punch. In 1912, at age 15, already with the build of a grown man, he had his first professional boxing fight, winning by knockout in the eighth round. He soon changed his name to Battling Siki as he felt white men could easily remember such a name.

Between 1912 and the breakout of World War 1 in 1914, he accumulated a record of 8 wins, 6 losses and 2 draws before enlisting in the French army as a 17 year old. Siki fought courageously for the French throughout the war in most of the major campaigns, performing heroic acts under heavy enemy fire which led to him becoming a highly decorated corporal that was awarded the Croix-de-Guerre and the Médaille Militaire for his courage in battle. He was in a regiment compiled mainly of whites and was the champion grenade thrower in his corps while with the colonials. He reportedly could launch a grenade 75 meters. He didn’t receive his first serious battle wounds until 1916 in the infamous “Battle Of The Somme” when bomb fragments went through both of his legs in the middle of the calf.

Rumors have him single handedly wiping out a machine gun nest full of German soldiers. In battle, he used what in boxing would become his trademark crouch that racist sports writers would later dub his “jungle crouch” as he snuck toward the German line where he launched grenades into trenches with wonderful aim. Conflicting reports have Siki successfully capturing nine German soldiers. One has a successful capture, while the other has Siki, worried that they will band together and charge at him, herd them into a shell hole where he quickly lobbed in a couple of grenades after them to do away with the risk.

While on a leave, Siki would mingle with nearby English corps’ as they regularly engaged in sport during downtime, namely boxing. He had a give and take battle with one of their men and was invited to stay for lunch where he was happy to eat a much better variety of food than what he was given by the French, this prompted him to continue boxing the Englishmen. From boxing the British soldiers, Siki learned sportsmanship. The Brits were not stylish boxers, but could absorb tremendous punishment, and dish it out too, which taught Siki how to take a punch. After the British soldiers were finished fighting a fellow, they would be friends again as it was all in sport, this led to Siki learning how to no longer take his anger at what transpired in the ring past the final bell.

Siki was honorably discharged from the French Army as a decorated soldier, and returned to Marseilles where he moved up from a pre war dishwasher to a post war waiter, a job he was given because the restaurant’s manager appreciated his service in the French Army. He continued to fight low level professional bouts. He made a bit of a reputation for himself as a boxer while mixing it up with the British soldiers, and was one day approached in his restaurant by a man while his hands were full of dishes who asked him if he would like to fight French Army champion Leon Derensy in Paris. Siki took the fight, and his manager allowed to him to take time off to train as he figured if his waiter got a name for himself as a boxer his restaurant would benefit from his fame. Siki knocked out Derensy in three rounds.

Even after this performance, he was going nowhere as a fighter. He lived to eat, drink, and smoke, and he used fighting as a means to afford these hobbies stating “In France I drink wine like a Frenchman, in Holland I drink beer like a Dutchman. Also, I smoke a good deal. When not training I like to be out with men smoking and talking and drinking.” Between the time of his discharge and the time he fought for the world light heavyweight title, Siki had fought 49 times with a record of 46-2-1, 21 KO’s, in those bouts. He spent time in the Netherlands where he fought a couple bouts, married a white woman, became a fan favorite, and spent time as a boxing instructor. During this impressive run, he held victories over top European fighters such as Harry Reeve and Marcel Nilles which earned him a shot at world famous light heavyweight champion Georges Carpentier who was the sporting hero of France.

Battling Siki would challenge Carpentier for his title on September 24, 1922. Georges Carpentier is regarded to this day as one of the greatest European fighters of all time. He had been successful against top tier fighters from welterweight all the way up to heavyweight, where he still packed a punch. He had movie star good looks, the demeanor of an absolute gentleman and fair sport, and immense popularity worldwide which was further bolstered by his highly publicized service in the French Army during World War 1 as a low flying observation pilot, often flying in harms way to carry out missions which, like Siki, earned him the distinction of being awarded the prestigious Croix de Guerre and the Médaille Militaire. He attracted droves of fans to the sport that would not typically be interested in prizefighting, but were excited to witness the squeaky clean celebrity war hero show off his pugilistic talents. A year earlier, as light heavyweight champion, Carpentier moved up in weight to face world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey in America, and such was his popularity that he was a major reason the bout generated boxing’s first million dollar gate. Dempsey, who reportedly dodged enlisting in the war effort, was actually cheered against by his fellow Americans who were hoping that the French war hero with the good looks, and the humble gentlemanly personality to match, would teach the infamous Manassa Mauler a lesson for being a coward in times of war.

Unfortunately for fans, and Carpentier, Dempsey was too good a big man for the former French welterweight, so Carpentier was overwhelmed and knocked out in the fourth round to the disappointment of fans everywhere. Prior to the Dempsey bout, Carpentier had traveled to the United States to face America’s Battling Levinsky for the world light heavyweight championship. Carpentier proved his worth in winning the title by fourth round knockout.

After losing to Dempsey at heavyweight, Carpentier returned to light heavyweight to defend his championship against all time great Ted “Kid” Lewis. Shockingly, Carpentier destroyed Lewis with a one punch knockout in the very first round. He then returned to France to defend his world title at home for the first time, which is when Battling Siki got the call to square off against the beloved celebrity hero of all of France in front of his adoring fans in Paris.

By the time they stepped into the ring in September of 1922, Carpentier was 28 years old with an outstanding record of 83-12-5, 52 KO’s, while Siki was 25 years old with a record of 49-9-3, 23 KO’s. Carpentier certainly had the edge in experience having fought Dempsey, Levinksy, and Lewis, while also facing formidable opposition in the form of Frank Klaus, Joe Jeannette, Billy Papke, Harry Lewis, and many others that were better than the very best men Siki had squared off with. Both Siki and Carpentier were roughly the same height, with Siki having a two inch reach advantage. Stylistically, Carpentier was a fine technical boxer with a powerful punch and blazing handspeed for a light heavyweight, while Siki fought out of a crouch and launched awkward and unorthodox attacks, at times reluctant, and at times relentless, but usually a difficult puzzle to solve.

Siki claims he had reneged on a promise to take a dive in the fight, and said throughout the bout he was consistently told to lie down by Carpentier who was expecting an easy night with a pre determined dive, but instead received an unexpected walloping. It’s unknown if this is a legitimate claim, or one that Siki invented to try and taint the clean reputation of the French hero in retribution for all of the nasty things that were written about him by the racist media who were horrified at the sight of their beloved champion falling to a black man that they said fought with an ugly style in a jungle crouch and mimicked a chimpanzee in battle, despite Siki never having witnessed a battle between chimps in his life. Siki claimed he was supposed to take a dive, but wasn’t supposed to suffer a beating in the process, so when he realized Carpentier was really trying to hurt him, he changed his mind about falling.

Carpentier took it to him from the opening bell with Siki not doing much offensively but occasionally coming forward in his awkward crouch. When Carpentier knocked Siki down twice in the third round with powerful right crosses, Siki said he abandoned any thought of taking a dive, and he responded with a four punch combination to the body and head to score a knockdown that shocked Carpentier. In rounds four and five, Siki continued his onslaught and dropped Carpentier again in the fifth.

In round six, Siki hit Carpentier with an uppercut that put him down for the count, however, the referee claimed Siki had tripped Carpentier on purpose and awarded the bout to the still floored Carpentier on a bogus foul. The crowd knew what they saw and began an uproar which prompted the three ringside judges to overrule the referee, crowning Battling Siki as the new king of the light heavyweights, and the first ever champion from the continent of Africa.

To say the media were not receptive to Siki’s courageous story from the streets of Senegal, to decorated war hero, to conquerer of the great Georges Carpentier, would be the understatement of the century. The media would engage in a smear campaign against a man in Siki who in reality was as much of a French hero as Carpentier, having been decorated with the same military honors for his service in World War 1. If Siki were not a black man, his unlikeliest of rags to riches story would have propelled him to idol status in France right alongside Carpentier, instead he was labeled a fighting chimpanzee employing a jungle crouch and the tactics of a wildman. The fact that he was a highly decorated war hero no longer held any value, he was the African who dared to try and destroy Carpentier’s messiah type reputation, and France would never forgive him.

In response to the poor press, Siki would say “A lot of newspaper fellows have written that I have a jungle style of fighting, and that I am a sort of chimpanzee who has been taught to wear gloves. I was never in the jungle in my life. I haven’t seen many chimpanzees and never saw any fight. Every fighting man builds up his own way of hitting the other fellow and of trying to keep from getting hit. Call it by what name you will, the whole game is to hit the other fellow and keep from getting badly hurt yourself. If I can bend and stoop in such manner that all the other fellow can hit is my elbow or the top of my head, that’s my game. He can’t hurt my elbow, and I have a black man’s head. It can stand a lot of bumping.”

It was in the aftermath of his championship winning KO of Carpentier that the legend of Siki’s outrageous out of ring escapades came to light. He engaged in a highly publicized rampage of partying and carousing. It wasn’t odd to see the athletically built black man walking his pet lion down the world famous Champs-Élysées in Paris, dressed to the nines in a tuxedo, cape, top hat and monocle. When he opted on strolls without his Lion, he would take his two great danes and was known to shoot off his revolver in the air as a signal to have his two giant dogs perform tricks. He was regularly reported as being intoxicated in various nightclubs, and he lavishly spent his earnings on flashy clothes and partying. He was particularly fond of white women, seen regularly with various white women by his side, and he actually married to two of them. Siki was consistently reported for being kicked out of Boulevard cafes on absinthe binges.

Eventually, offers began to pour in to the newly crowned light heavyweight champion from the United States. There were rumors of a lucrative offer to move up in weight to face heavyweight kingpin Jack Dempsey, among offers to face Harry Greb, Harry Wills, and middleweight champion Johnny Wilson. Oddly, Siki chose to defend his title against unheralded Irishman Mike McTigue in a less publicized bout on Saint Patrick’s Day, in Ireland, six months after winning his title. By agreeing to face an Irishman in Dublin, Ireland on Saint Patrick’s Day, Siki allowed the cards to be heavily stacked against him. It was another bad decision in a long line of poor decisions, with more to come, for the 25 year old Siki.

By all accounts Siki was the only man fighting for his title that Saint Patrick’s Day. At times he launched furious attacks at McTigue who appeared as if he was just trying to survive in a defensive posture without mounting any offense, other than the occasional pawing jab. The New York Times reported that with four rounds remaining, the Irishman was losing by a wide margin and would need a knockout to win. At the fights end, Siki had clearly battered his first title challenger, but somehow the referee awarded Irish Mike McTigue Siki’s world title in one of the most overtly corrupt robberies in championship history. Not surprisingly, the referee’s scorecard would go missing to erase any evidence of such corruption. Siki would get raked over the coals by the racist media once again. His wartime heroics purposely forgotten, they couldn’t resist rubbing salt in the unjust wounds of the man who dared to beat the beloved Georges Carpentier. Prior to the McTigue fight, Siki grew paranoid with good reason. He was locked in his boat cabin on his way to Dublin, and became convinced that everyone was out to get him. Before the fight, he refused to weigh in and demanded he be paid in advance. He actually had much of his purse for the bout sewn into a belt that he wore during, and after the fight. To further complicate matters, after he was robbed of his world championship, Siki had to remain in hostile Ireland for two weeks with his Dutch wife as he had been outlawed from reentering Britain.

Siki would return to France for three more bouts, and would then make a highly publicized move to the United States in late 1923. His move was well reported in America, largely due to his colorful out of ring antics. In America, Siki’s talent was quickly fading due to his lifestyle and lack of discipline. He would never again win a significant bout. From the time he moved to the US, until the time he was murdered, he went a poor 8-15-1, 6 KO’s. He continued his party hard ways, walking the rough Streets of New York and engaging in drunken street fights.

He was regularly accused of taking long taxi trips around Harlem then refusing to pay the fares, offering cabbies to fight him for the money owed. He gained a reputation for getting intoxicated in speakeasies, refusing to pay his tab, then fighting his way out. These instances culminated in various arrests for disorderly conduct. Despite his fervid spending on booze, clothes, and partying, Siki would regularly dole out hundreds of dollars to people he liked, or felt needed it. He once gave his entire purse for a bout to passengers on his ferry ride home from the fight.

There are several reports of him leaving home in his expensive clothes and returning in nothing but his underwear because he gave his nice clothes to someone he felt could benefit from them. Siki was arrested in July of 1925 for slashing at a Policeman with a knife, which led to the US government initiating deportation proceedings. France actually refused to accept his deportation. A month later, an emotional and sobbing Siki was brought before the boxing commission and suspended while his American manager was told to keep Siki out of the three mile radius of New York City.

Aside from his erratic behavior while in drunken stupors, he was generally regarded as kind hearted, fun loving man. Siki was known to be a dangerous drunk, and after smashing up a speakeasy in New York’s notorious Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood in August, he was stabbed in the back. In December, he was fined for slapping a Policeman. There was no doubt that within his short tenure as a resident of Hell’s Kitchen, Siki was its most notoriously troublesome citizen.

Siki’s torrent and tumultuous fall from grace came to a boil on the night of December 14 of 1925. In the early evening, he told his new American wife that he was going out with the boys and would return in time to pack for their trip to Washington the next day, where he was scheduled to appear in a theater. Shortly after midnight, a patrol officer who was familiar with Siki saw him wobbling near Forty First Street and was told by Siki that he was on his way home. Shortly after 4 am on December 15, 1925, the same Patrolman noticed a body a hundred feet east of the corner in the gutter in front of 350 West Forty First Street. As he approached the body, he recognized Siki. Siki had bullet wounds in his chest and abdomen. About forty feet east of where Siki’s body was discovered, detectives found a pool of blood which suggested Siki tried to crawl home after being shot. They also found the gun that had been used to cut Siki’s life short in front of a building across the street. Later, autopsies revealed that Siki had been shot through his lungs and kidneys. Surprisingly, autopsies also showed that Siki suffered from an anemic condition.

At his funeral, fittingly, Siki’s body was clothed in the finest of evening dress as he would have no doubt wished. He left behind, on record, no father, mother or child, when he died in one of societies most destitute manifestations.

The murder of Siki remains virtually unsolved to this day. An eighteen year old who lived near Siki’s house was booked on a homicide charge in March of 1926. The suspect signed two statements, one of which said he saw Siki stumble into a cafe where he threw a chair at a gathering of eight men including the suspect before exiting. The young man said that he lured Siki to the cafe with the promise of buying him a drink. He claimed as Siki left the cafe, he followed and was joined by two men outside, one of which shot Siki in the back two times. The young man was held in custody for five months, but was released by the court because the state was not satisfied with the case.

Finally, in 1993, Siki’s remains were repatriated to Saint Louis, Senegal where he currently rests as Africa’s very first world boxing champion.

“There are places on a man's head that are as hard as a rock. Your head's actually stronger than your body. And you don't have too many instruments up there workin'. But you got a lot of tools workin' in that body: the liver, the kidneys, the heart, the lungs. You soften that up and see what happens. I lived by the body shot. -”Smokin’ Joe Frazier

Joe Louis hung up his gloves as world heavyweight champion in March 1949, unfortunately, Louis' retirement did not last. Broke and hounded by the IRS, he returned to the ring after little more than a year to face Ezzard Charles, who had acquired the title Louis vacated with a decision over Jersey Joe Walcott.

Probably the greatest light-heavyweight of all time (though he never held that title), Charles was undersized as a heavyweight. Louis, though, was at 36 only a shell of the fighter who had ruled the division for almost twelve years, and Charles easily pounded and outpointed him in 1950 at Yankee Stadium.

“No, I’ll never fight again,” Louis said afterwards. He did, of course.

“I wouldn’t say Charles is the best fighter I’ve ever faced. But he’s a good fighter, good in all departments.”

“I knew from the seventh round on I couldn’t do it. It wasn’t a case of reflexes or anything. I just didn’t have it."

Mexican welterweight legend Jose "Pipino" Cuevas. He left a trail of broken bones, eye sockets, jaw, cheek bones, noses, and ribs. Great puncher, his left hook was legal murder. Pipino Cuevas’ story doesn’t start with glittering belts or sold-out arenas. It begins with a kid barely into his teens, gloves laced up, standing in the shadow of men. He turned professional at fourteen—an age when most boys are still finding their place on a schoolyard, not inside a ring. His first dozen fights were a reminder that greatness doesn’t always announce itself early—seven wins, five losses. But there was grit there, something in the way he kept showing up. Then came an eight-fight winning streak, a quiet warning that this kid was learning fast.

That streak ended with a loss to Andy Price. It could’ve been a breaking point. For Cuevas, it was just another step. By the summer of 1976, the unlikeliest of doors opened—a shot at the WBA welterweight title against Ángel Espada. No one was supposed to see what happened next. On July 17, Cuevas dropped Espada three times in the second round, shocking the boxing world. At just 18, he became the youngest welterweight champion in history.

He didn’t ease into his reign. First defense? A trip to Japan to face Shoji Tsujimoto in front of his own crowd. Cuevas stopped him, too. Then came Argentina’s Miguel Angel Campanino—a man with 84 wins, only 4 losses, and riding a 32-fight win streak. People thought this was the one who’d slow the young champion. Cuevas ended it in two rounds.

And that became a pattern. Clyde Gray, a Canadian veteran who’d been stopped only twice in 58 wins—Cuevas finished him in the second round. He broke Espada’s jaw in their rematch. Harold Weston? Broken jaw and ribs, done in the ninth. Former champ Billy Backus? Fractured orbital bone, gone in one round. Pete Ranzany in Sacramento? Cuevas silenced the hometown crowd in round two. Scott Clark? Another second-round knockout.

Finally, in Randy Shields, he met someone who could last the distance, winning a decision. But that was an exception. He stopped Espada a third time in 1979, beat South African champion Harold Volbrecht in five, and seemed untouchable.

Then came 1980. Detroit. A young, unbeaten Thomas Hearns—taller, longer, sharper. Cuevas couldn’t get close. The second round bell was still ringing in the crowd’s ears when Hearns’ right hand ended the fight. That night marked the turning point.

The champion who had bulldozed through eleven title defenses over four years began to fade. The names stayed big—Roberto Durán, Jorge Vaca, Lupe Aquino—but the results shifted. Durán stopped him in the fourth. Losses piled up. By 1989, he walked away for good.

Cuevas fought in an era stacked with welterweight brilliance—Sugar Ray Leonard, Wilfred Benítez, Carlos Palomino, Hearns, Durán. He was part of that golden mix, even as his reign wound down when those legends were just rising. Still, in those years, he faced the best available, his opponents combining for a staggering 505-70-29 record.

The boxing world didn’t forget. In 2003, The Ring ranked him among the 100 greatest punchers ever, placing him at number thirty-one. A year earlier, he’d been enshrined in the International Boxing Hall of Fame—a permanent reminder that Pipino Cuevas’ reign, brief as it might have been in the long arc of boxing history, was pure, unfiltered thunder.

If you blinked during his fights, you often missed the ending. And maybe that’s the best way to remember him—not for how it ended, but for how suddenly, violently, and beautifully it all began.

There's not too many fight photos of Pipino Cuevas for some reason, but there are some good images of him. Cuevas usually had a scowl on his face, and a cold, icy stare. He had a very serious demeanor and mindset. This is the hurt business, you either hurt or be hurt and he wasn't showing up at the arena to play hopscotch with his opponents.

This is a couple of fight photos from Cuevas career and you can see how destructive his punching was. The first two are from his second fight with Angel Espada, he broke Espada's jaw in that fight. The last one is his KO of Pete Ranzany.

Pipino Cuevas was known for inflicting serious damage with his punches, especially his left hook. He actually holds the record for most facial bones broken in title challengers, and the total number of broken bones across all his opponents. A real Bonecrusher if there ever was one.

Pipino Cuevas throws a punch at Randy Shields. Shields was one tough son of a gun, he was the only one to survive the distance against Cuevas during Cuevas' title reign, everyone else got brutally stopped or KO'd.

Pipino Cuevas was really aggressive when he had an opponent hurt, when he smelled blood in the water, it was almost impossible to escape. This is the destructive power of Pipino Cuevas.

Floyd Mayweather grew up in a boxing family, but nothing was easy. His father was in prison, his mother battled addiction, and Floyd used the gym as his escape. What came out of it was perfection. His defense was untouchable, his timing razor sharp and his record unblemished. Fifty fights, fifty wins. He made more money than anyone in boxing history. But that’s the information that people only see. They don’t see where his drive and dedication came from, it came from hardship, and the refusal to let history repeat itself.

"El Matador" aka "El Loco", Ricardo Mayorga, Nicaragua's two-division world champion and wildman. I can't even repeat some of the stories about Mayorga on this forum, he was a loose cannon, totally out of control. He just may have been the craziest man to ever enter a boxing ring. He used to smoke and drink liquor during training camp, he would even light up a cigarette in the ring after a fight. He grew up in a violent atmosphere in Nicaragua, he was in a street gang and he was almost killed by a gun blast but got lucky when the gun jammed, he had his head split open by a lead pipe and had scars from knife fights on his body. He was also a self confessed drag racing enthusiast that enjoyed speeding through junctions on a red light and who once made Carl King, son of his promoter Don King, vomit following a daring manoeuvre that saw him drive under a trailer carrying a shipping container. His father used to beat him when he was young and he credited that for making him tough in the boxing ring. As far as his style goes, Mayorga had a rough and wild "search and destroy" boxing style, often described as barroom-like, characterized by powerful, lunging punches and a relentless, aggressive approach. Mayorga had an iron chin with underated skills on the inside, heavy hands and great stamina, who was happy to walk through shots to land his own, it was often difficult to keep Mayorga off of you. His style was complemented by a notorious persona featuring bullying bravado, swagger, and of course the post-fight beer and cigarette celebrations.

Mayorga beat the great Vernon "The Viper" Forrest twice, Forrest is one of the greatest technical boxers the sport has ever known, I love watching film of Forrest, he's one of my favorite fighters, but Mayorga just blitzed him in both fights and Forrest just couldn't do anything with him. Styles make fights and Mayorga's wild shootout style created problems for Forrest. You might say that Mayorga was Forrest's Kryptonite.

Mayorga-Forrest I

"El Matador" Ricardo Mayorga scored a big upset when he unified the WBC and WBA welterweight titles with a 3rd round TKO of Vernon Forrest at the Pechanga Resort & Casino in Temecula, California #OnThisDay in 2003.

After defeating Shane Mosley two times in a row and proving his pound for pound level ability, Forrest signed to face the relatively unknown Mayorga and was installed as a significant favorite.

Mayorga taunted Forrest before the bout by eating at the weigh-in and talking trash at press conferences, then succeeded in dragging Forrest into a messy fight early. At the end of round 1, Mayorga landed a glancing left hand that, with the help of a footing issue, put Forrest down.

The fight settled slightly, but in round 3 a right hand put Forrest down against the ropes. Mayorga seemed to fall into Forrest with a forearm to the face, and Forrest rose looking shell-shocked. When he didn't clearly answer the referee, the fight was stopped.

"In order to eat good food, you must cook it," Mayorga said. "I first cooked in training camp, and tonight I came to eat."

Mayorga also beat Fernando "El Ferocious" Vargas in 2007 by 12-round majority decision, with knockdowns in the first and eleventh rounds contributing to his victory and capturing of the WBC Continental Americas Super Middleweight title. Vargas was a blood and guts Mexican warrior, a real gladiator, Vargas was the type of fighter that would legit rather die than surrender.

Ricardo Mayorga vs Cory Spinks in 2003, Mayorga had a chance to become unified WBA, WBC, and IBF welterweight champion in this one. Mayorga was vicious as heck in this fight, he came busting through the door like gangbusters, throwing hard lead at Spinks, but Mayorga lost the fight because of his fouling and roughhousing tactics. For the record, Cory Spinks is the son of Leon Spinks and nephew of Michael Spinks, and Cory is a fine ring technician and he did a good job of avoiding Mayorga's wild charges and countering him. Still, I have to say, Mayorga is fun to watch, he always wanted to make a fight into a shootout and his style was fun to watch. Here are a few images from that fight and you can see how aggressive and brutal Mayorga was as a fighter. Mayorga wasn't gunshy, he came to fight and he really went after his opponents.

Howard Winstone, aka "The Welsh Wizard", one of the greatest pure boxers the sport has ever seen, British, European, and world featherweight champion, and what's crazy is he accomplished all of this while missing three fingertips on his right hand. "Science over slugging", that was Howard Winstone. He relied on strength, guile, workrate and body shots, allied to an outstanding technique. Beautiful fighter to watch on film.

British Vintage Boxing

HOWARD WINSTONE - THE WORLD AT HIS FINGERTIPS

"If I could find a boxer as good as Howard Winstone I would make millions. He's the nearest I have ever seen to the great Willie Pep." - Angelo Dundee

Have you heard the one about the orthodox boxer who lost three of his fingertips in his right hand and went on to become featherweight British, European and world champion? Ladies and gentlemen, there’s no punchline to this, because, Howard Winstone was no joke.

Born at 96 High Street, Penydarren on 15 April 1939, shortly before the start of World War II, the boy from the valleys didn’t evolve from any fistic lineage. His inspiration came from ‘The Merthyr Marvel,’ Eddie Thomas, who was the former British and European welterweight champion, who would eventually go on to train and manage Winstone as a professional.

During his amateur years, Winstone had earned a reputation of a rough fighter, willing to brawl at the drop of a hat. However, Merthyr Tydfil’s favourite fighting son was the victim of an unfortunate accident on 19 May 1956, when a metal press landed on his right hand whilst working at the Line’s Brothers toy factory in Cyfarthfa, which saw the tops of his three middle fingers severed.

Winstone was hospitalised for a couple of weeks and received compensation of a mere £1,900. Despite not being able to make a fully clenched fist with his right hand, this certainly did not deter him from becoming one of Wales’s most prolific fighters.

Recovering from the accident, Winstone, alongside trainer Thomas, adapted his fighting style to his tools. The jab now became a far more potent part of his armoury, referred to by many as his ‘piston left.’ Thomas, who also went on to train Ken Buchanon, put Winstone through an incredibly gruelling regime, split between his Penydarren gym and the steep inclines and terrain of the Breacon Beacons.

Winstone totalled 86 fights as an amateur, losing only three, however, it was 1958 that was a particularly memorable year for young Winstone as he was crowned ABA and Welsh bantamweight champion, then later the same year he beat Oliver Taylor from Australia to gain Commonwealth gold. It’s worth noting the importance of the gold medal, because the Commonwealth (Empire) Games were hosted in Wales and Winstone was the only competitor, across all the sporting disciplines from Wales to gain gold, despite a healthy collection of silver and bronze being collected by his fellow countrymen. This consequently earned him BBC Wales Sports Personality of the Year, an accolade he would gain a further two times, in 1963 and 1967.

Despite being a hot contender for a medal at the 1960 Olympics in Rome, Winstone got married at the age of 17, became a father soon after and needed to put food on the table. With the amateur ranks void of cashflow, on 24 February 1959, 19-year-old Winstone made his professional debut against Londoner, Billy Graydon at Wembley Stadium, fighting on the undercard of Willie Pastrano versus Joe Erskine.

Winning a comfortable points decision, and getting paid a mighty £60 for his performance, Winstone went on to rack up a further 23 victories on the bounce, before challenging Canning Town’s blue eyed boy, Terry Spinks, on 2 May 1961 at the Empire Pool, Wembley. The British featherweight title was on the line.

Spinks had won Olympic gold at the age of 18 back in 1956 and had fought 39 times as a pro at this point, having lost only four times. Despite a lesser CV in terms of experience and weighing over three pounds under the featherweight limit, with the opportunity to gain the British title, Winstone claimed victory over Spinks by TKO in the tenth of 15 scheduled championship rounds.

1962 was certainly a busy one for the young Welshman. Bearing in mind Winstone was not considered a puncher by many, due to his hand defect, in his nine fights this year, he won five by stoppage, which included two defences of his British title, against Derry Treanor and Harry Carroll. The Carroll victory was that bit more special because he fought at the Maindy Stadium, Cardiff and by the virtue of making his second defence of the British strap, he had won the Lonsdale belt outright. This made him the first Welshman to do so in 40 years.

However, the man from Merthyr did incur his first professional loss in his thirty fifth contest, against heavy handed American, Leroy Jeffery, getting knocked down three times in the second round, before the referee jumping in and bringing the contest to a halt with 30 seconds left of the round.

Not one to stop and lick his wounds, Winstone bounced back with two, third round stoppage victories to see out 1962 and started 1963 in blazing fashion, stopping Johnny Morrisey in the eleventh session, defending his British title for the third time.

Three months later, Winstone stopped Frenchman, Gracieux Lamperti in eight rounds, which was a significant win, because Lamperti was the former European featherweight champion. He lost the strap on points against Italian, Alberto Serti in August 1962, so there was only one thing for Winstone to do now – take on the man, that beat the man.

On 9 July 1963, Winstone took on Serti at the Maindy Stadium in front of 10,000 fans, claiming victory with a fourteenth round stoppage, to the elation of the Welsh crowd. With 40 fights to his name, with only one loss, 24-year-old Winstone had announced himself on the world stage.

Not one to enjoy the spoils of a massive victory, five weeks later, Winstone was up against Yorkshireman, Billy Calvert, successfully defending his British and European featherweight straps, at Coney Beach Arena, Porthcawl. A month later he beat Spanish featherweight champion Miguel Calderin on points, before defending his titles against Australian born, Glaswegian, John O’Brien at the National Sporting Club, Piccadilly.

Despite a points loss against Los Angeles resident, Don Johnson (not the guy from Miami Vice) in January 1964, the rest of the year panned out nicely for Winstone, clocking up a further six victories, including stopping Italian featherweight champion, Lino Mastellaro en route to defending his European title.

Working his way around the various champions within Europe, on 22 January 1965, Winstone secured a points victory over Algerian born French featherweight champion, Yves Desmarets, at the Palazetto dello Sport in Rome in front of 15,000 people.

In the following five months, Winstone extended his record to 52-2, which included avenging his loss to Don Johnson and earning a very respected points victory over future two time WBC world featherweight champion in the making, Cuban born Spaniard, Jose Legra. Unsurprisingly, Winstone was granted a shot at the WBA & WBC world featherweight champion, ‘El Zurdo de Oro’ (roughly translated, the Golden Leftie),Vicente Saldivar. The Mexican southpaw had only fought 29 times at this point, losing only once. In his 28 victories, he had arguably fought tougher opposition than Winstone, en route to world honours, beating the likes of Ismael Laguna, Sugar Ramos and Raul Rojas.

On 7 September 1965, the pair locked horns at Earls Court Arena, Kensington in front of a 12,000 strong crowd, for what would be part one of a prolific trilogy. Despite giving it his all, after 15 hard fought rounds, Saldivar edged the close scorecards to retain his straps.

Winstone had to wait 21 months before getting another crack at Saldivar’s titles, during which time he defended his European title three times, including a respected fifteenth round stoppage over Italian, Andrea Silanos in his hometown of Sassari, Sardina. Winstone also defended his British strap once and beat Don Johnson once again, in the final part of their trilogy.

On 15 June 1967, Winstone and Saldivar fought again, but this time at Ninian Park, Cardiff. The teak tough Mexican managed to knock down Winstone twice in the fourteenth round, which was the deciding factor, as referee, Wally Thom (old opponent of Winstone’s trainer, Eddie Thomas from 1951) scored the bout 73¼ - 73¾. A mere half a point separated them, which caused a huge outcry from those in attendance and the boxing media. There was only one thing to do - run it back again.

On 14 October 1967, the pair fought in Saldivar’s backyard at the Estadio Azteca, Mexico City. With the additional motivation to put on a performance in front of his home crowd, the Mexican champion put Winstone on the canvas in the seventh and twelfth rounds, before manager, Thomas threw in the towel. That made it 3-0 to Saldivar, but the fight took a lot out of the Mexican. Shortly after, he retired…….albeit, he returned two years later and went on to become a two time world featherweight champion. Winstone did however become a crowd favourite with the Mexicans and was given an open invitation from his old foe, now good friend, Saldivar, to return whenever he wished.

Many fighters would have considered hanging up the gloves after 64 fights (59-5), especially after two gruelling 15 round world title challenge losses, but Winstone was made of different stuff. On 23 January 1968, he took on Mitsunori Seki from Japan, for the vacant world WBC featherweight title. The pair had something in common, in so much as they had both challenged three times for world featherweight honours and had been unsuccessful. Incredibly, five of the six challenges between them were lost to the same man - Saldivar.

Both fighters acknowledged the miles on their respective clocks and knew that a loss should translate to retirement. That night at the Royal Albert Hall, London, Winstone achieved his lifetime goal in boxing to be crowned champion of the world, boxing beautifully and stopping Seki in the ninth after incurring terrible cuts over his eyes. Winstone returned to Merthyr to a hero’s welcome, with over 5,000 people lining the streets of Merthyr Tydfil and a party which lasted for several days. Seki in the meantime retired.

Seki said of Winstone at a later date, ‘It was in 1968 on a cold, snowy January day that we faced each other in the ring at the Royal Albert Hall fighting for the World Featherweight title. Our fight was to be the last of my career and I can still remember the crowded hall with the audience in their smart dress. As a boxer, Winstone was a great technician, with a superb variety of left hand punches. Thinking back to that fight, it was this skill that won him the title.’ Winstone said, ‘This the greatest moment of my life - I thought I’d never be champion.’ (Walesonline.co.uk)

Saldivar was in the crowd the night Winstone won the world title and was one of the first to hug and congratulate the Welshman, before presenting him with world championship honours in front of 6,500 attendees. Rumours started to circulate that a fourth contest was in the pipeline as the Mexican indicated to the media a possible return to the ring. However, Winstone’s retirement was only six months behind Seki’s, after losing to old foe, Jose Legra via fifth round stoppage, in a fight named by some as, ‘The Brawl in Porthcawl.’ On 24 July 1968, the Welshman was knocked down in the first round at Coney Beach Arena, but by the fifth, his eye was so badly swollen the contest had to be stopped to ensure he didn’t absorb further unnecessary punishment.

Aware that his speed and reflexes were not what they used to be, Winstone retired at the age of 29 with a very plausible record of 61-6. His resume included holding the British title for six years, the European strap for four and he reached boxing Everest by becoming WBC world featherweight champion. The year after, Winstone was awarded the MBE for his accomplishments in the square ring, in addition to being made a Freeman of Merthyr Tydfil.

Winstone sadly passed away in 2000 from kidney disease, at the age of 61, at the Prince Charles Hospital in his beloved hometown of Merthyr Tydfil. He was survived by his wife, two daughters and four sons. The year after a fitting legacy was left in Merthyr Tydfil’s square, as a bronze statue was unveiled of their favourite fighting son. If that wasn’t enough, in 2005 he was named ‘Greatest Citizen of Merthyr Tydfil.’

The final cherry on Winstone’s cake was a film about his life, which was released in 2011, which starred a host of well known actors and boxers, including Shane Ritchie, John Noble, Stuart Brennan and Eril ‘El Terrible’ Morales.

Is Howard Winstone one of the best boxers Wales has ever produced? You would have to provide a very strong argument to say he didn’t belong in the top 10 of all time as one of the most elegant technicians, who possessed the engine of a steam train.

Comments

Johnny Kilbane actually a few statues honoring him, one in his native Ireland and one display in Cleveland Ohio. This is the one on Achill Island in Mayo Ireland.

This is my favorite statue of Johnny Kilbane, it's a display in Cleveland Ohio showing the three stages of his life.

Tony Zale, the "Man of Steel" floors Rocky Graziano, "The Rock", during one of the fights in their trilogy. Their rivalry was one of the most violent in boxing history, each of their three fights was a life-and-death struggle that ended with a brutal knockout.

This is one of the most beautiful knockouts you'll ever see, Tony Zale-Rocky Graziano III. Watch Zale land a shot to the body of Graziano and then finish him with a left hook. Just a thing of beauty.

Tony Zale was one of the greatest body punchers in boxing history, he really knew how to tear your body up. Years after their trilogy, Rocky Graziano said he still had nightmares about Zale punching his body. The great Billy Soose, who fought Zale, once said about being punched in the body by Tony Zale, "When he hits you in the belly, it's like someone stuck a hot poker in you and left it there."

Battling Siki was the first African born boxing world champion, born in French-Senegal. He won the world light heavyweight championship after knocking out Georges Carpentier in 1922, one of the most bizarre fights in boxing history. It was supposed to have been a fix, Carpentier was supposed to go easy on Siki and Siki was supposed to lose, but Siki became enraged after Carpentier began pouring it on him. What transpired in this fight was chaos and has become part of boxing lore.

Battling Siki stands over a bloody Georges Carpentier during their infamous encounter

The Fight that Wouldn’t Stay Fixed

How an apparent misunderstanding led to a brawl that turned into a donnybrook that became a legend

Despite the promoters’ best efforts, the 1922 light-heavyweight fight between the popular European champion Georges Carpentier and an obscure Senegalese brawler named Amadou Mbarick Fall, better known as “Battling Siki,” wasn’t supposed to be much of a fight. In the run-up to the September 22 event, newspapers confidently reported that fight fans could “expect to see the French idol win inside of six rounds.”

And yet more than 50,000 Parisians flocked to the Buffalo Velodrome in France, creating the first “million-franc” boxing match. Carpentier was a war hero beloved by his countrymen, and even though he had a lackluster record, Battling Siki was more than willing to help stir up interest in the fight. He was billed as the “Jungle Hercules,” and reporters described him as a man who fought “like a leopard,” with “great muscles” rippling under his dark skin and “perfect white teeth so typical of the negroid.” Siki had taken a hit on the head with a hammer, one paper stated, “and scarcely felt it.”

Even Siki’s own manager, Charlie Hellers was quick to point out the fighter’s “gorilla’s skill and manners” to reporters. “He’s a scientific ape,” Hellers said. “Just imagine an ape that has learned to box and you have Battling Siki.”

For his part, Siki told reporters that he was going to knock Carpentier out in the first round because he had plans to fight the world heavyweight champion next. “Tell Jack Dempsey he’s my next meat,” Siki was quoted as saying.

In truth, the fighter was born and raised in the Senegalese city of Saint-Louis and moved to France as a teen. “I have never even seen a jungle,” he would say later. He was often spotted around Paris dressed in expensive suits and fancy hats, sometimes with his pet monkey perched on his shoulder. His training, it was said, consisted of “caviar and cognac,” and he preferred doing his “roadwork on a dance floor.”

On the afternoon of September 22, fight fans packed the velodrome to see Carpentier defend his title. Nicknamed the “Orchid Man” for the corsages he often wore with his tailored suits, Carpentier had been fighting professionally since he was 14. Although he was coming off a failed attempt to win Dempsey’s heavyweight title, he’d helped secure boxing’s first million-dollar gate. Fighting again as a light-heavyweight, the Frenchman’s future was still bright—so bright that Carpentier’s handlers were taking no chances. They offered Battling Siki a bribe to throw the fight. Siki agreed, under the condition that he “didn’t want to get hurt.” What followed was one of the strangest bouts in boxing history.

Although Siki later admitted that the fight was rigged, there’s some question as to whether Carpentier knew it. Early in the first of 20 scheduled rounds, Siki dropped to a knee after Carpentier grazed him, and then rose and began to throw wild, showy punches with little behind them. In the third, Carpentier landed a powerful blow, and Siki went down again; when he got back on his feet, he lunged at his opponent head first, hands low, as if inviting Carpentier to hit him again. Carpentier obliged, sending Siki to the canvas once more.

At that point, the action in the ring turned serious. Siki later told a friend that during the fight, he had reminded Carpentier, “You aren’t supposed to hit me,” but the Frenchman “kept doing it. He thought he could beat me without our deal, and he kept on hitting me.”

Suddenly, Battling Siki’s punches had a lot more power to them. He pounded away at Carpentier in the fourth round, then dropped him with a vicious combination and stood menacingly over him. Through the fourth and into the fifth, the fighters stood head to head, trading punches, but it was clear that Siki was getting the better of the champion. Frustrated, Carpentier charged in and head-butted Siki, knocking him to the floor. Rising to his feet, Siki tried to protest to the referee, but Carpentier charged again, backing him into a corner. The Frenchman slipped and fell to the canvas—and Siki, seemingly confused, helped him get to his feet. Seeing Siki’s guard down, Carpentier showed his gratitude by launching a hard left hook to Siki’s head just before the bell ended the round. The Senegalese tried to follow Carpentier back to his corner, but handlers pulled him back onto his stool.

At the start of round six, Battling Siki pounced. Furious, he spun Carpentier around and delivered an illegal knee to his midsection, which dropped the Frenchman for good. Enraged, Siki stood above him and shouted down at his fallen foe. With his right eye swollen shut and his nose broken, the Orchid Man was splayed awkwardly on his side, his left leg resting on the lower rope.

Siki returned to his corner. His manager, Charlie Hellers, blurted out, “My God. What have you done?”

“He hit me,” Siki answered.

Referee M. Henri Bernstein didn’t even bother counting. Believed by some to be in on the fix, Bernstein tried to explain that he was disqualifying Siki for fouling Carpentier, who was then being carried to his corner. Upon hearing of the disqualification, the crowd unleashed a “great chorus of hoots and jeers and even threaten the referee with bodily harm.” Carpentier, they believed, had been “beaten squarely by a better man.”

Amid the pandemonium, the judges quickly conferred, and an hour later, reversed the disqualification. Battling Siki was the new champion.

Siki was embraced, just as Carpentier had been, and he quickly became the toast of Paris. He was a late-night fixture in bars around the city, surrounded by women, and he could often be seen walking the Champs-Elysees in a top hat and tuxedo, with a pet lion cub on a leash.

Carpentier fought for a few more years but never never reclaimed his title. Retiring from the ring, he toured the vaudeville circuits of the United States and England as a song-and-dance man. Battling Siki turned down several big fights in the United States to face Mike McTigue in Ireland. That the bout was held on St. Patrick’s Day in Dublin was likely a factor in Siki’s losing a controversial decision. He moved to New York City in 1923 and began a downward spiral of alcohol abuse that led to countless confrontations with the police. By 1925, he was regularly sleeping in jail cells after being picked up for public intoxication, fighting and skipping out on bar debts.

In the early hours of December 15, 1925, Amadou Mbarick Fall, aka "Battling Siki", was wandering through the Hell’s Kitchen section of New York’s West Side when he took two bullets in his back and died on the street. Just 28 years old, Siki was believed to have been killed over some unpaid debts, but the homicide remains unsolved. Adam Clayton Powell presided over Siki’s funeral in Harlem, and in 1991, the pugilist’s remains were brought back to Senegal.

Battling Siki wasn't very skilled but he was a very tough and wild brawler with brutal power in his punches. He was savage not just in the ring, but as a person, he drank a lot, he even drank before fights, and could be very mentally unstable. He was a handful for anyone that stepped in the ring with him.

More photos from Battling Siki vs Georges Carpentier.

Battling Siki celebrates after the Carpentier fight.

Battling Siki vs "Bold" Mike McTigue was one for the books, McTigue was a clever scientific Irish light heavyweight boxer. This fight took place in Dublin Ireland in 1923, and at the time there was a civil war raging in Ireland, you could actually hear machine gun fire in the streets and the police presence was heavy due to a bomb threat, and one exploded near the venue as the boxers were entering the ring. Two children were injured and nearby windows were blown out by the blast. Mike McTigue won the title in a 20-round points decision, making him the first Irishman to win a world title on Irish soil. It was a very controversial fight, with some thinking Siki should have won. A lot of people think that McTigue got the decision because of home cooking. I've seen footage of the fight and from what I've seen I think McTigue rightfully got the decision, he boxed very cleverly, but McTigue did have his hands full with Siki, he had one hell of a time trying to deal with Siki's wild and vicious attacks.

Battling Siki is one of the most fascinating fighters you'll ever read about. He had a wild life.

Battling Siki: One of Boxing’s Most Interesting Stories

By Travis “Novel” Fleming

Former 1920’s light heavyweight champion Battling Siki, 60-24-4, 31 KO’s, has always been a fighter that piqued my interest. By all accounts, he was one of the most flamboyant, strange, unique, and heroic, characters in the history of boxing. His story is a true rags to riches tale, against all odds. His meteoric rise to the top of the boxing world came just as quickly as his tragic fall and unsolved murder.

The first time I heard about Siki was in an excellent book about tragic boxing stories. I wish I could remember the book’s name or author as it would have been a great point of reference for this article. Anyways, moving along, the book had chapters devoted to various boxers whose careers or lives ended in tragedy, and there was a chapter all about Battling Siki that reeled me in. I checked the book out of my local library as a youngin, and, like anyone in my generation of low attention spans, I immediately went to the middle of the book to flip through the glossy picture section where I was instantly drawn to a dapper young black man in a top hat that was sporting a tuxedo, an opera cape, and a monacle, while holding the leash of a giant lion, which stood by his side.

The caption mentioned something along the lines of “Former light heavyweight champion Battlin Siki walking his pet lion in the streets of Paris.” This was enough to convince me that the chapter on Siki should be my starting point. I was fascinated by his rise from poverty in his native Senegal, to his heroics in World War 1, to his light heavyweight championship winning effort, but most of all it was the stories about his crazy lifestyle outside of the ring that stuck with me to this day. From his flashy dressing, heavy drinking, love of absinthe, and his run ins with the law, to his pet lion that he would walk around major cities with while shooting his gun in the air in case people weren’t already paying undivided attention to the flashy black man with the giant beast.

The story of Battling Siki never fails to stick out to me as one of the most interesting in the history of boxing, so I figured I’d do my best to enlighten those who have yet to hear about this interesting character. This is by no means a complete biography, and there are many conflicting reports on Siki’s life, behavior, and in ring accomplishments. This article’s purpose is just to shed some light on one of boxing’s most unique champions for those who haven’t heard of his exploits. Those that have read up on Siki will likely be familiar with everything mentioned in my shoddy short summary of his tale.

Battling Siki was born in the late 1800’s in the French colony of Senegal, Africa. His family was very poor and times were tough, as they were for the vast majority of his countrymen. At just eight years old in his hometown of Saint Louis, while partaking in his hobby of watching the port city’s harbour traffic, a rich German dancer got off a ship that was en route to Marseilles, France, and asked the young Siki, at the time known by his birth name Baye Phal, or Amadou M’Barick Fall, if he could show her around the city. Siki obliged, and the dancer took quite a liking to him. The lady’s name was Mme Farquenberg and she asked the young Baye Phal if he would like to accompany her to France where she would assure he’d be taken good care of.

The ship was departing shortly after her proposition, and fearing she might change her mind, Baye Phal agreed to join her and left for France without even being able to notify his family that he may never see them again. In France, the lady taught him how to read and write, bought him nice clothes, and made sure his belly was full. Eventually, the dancer had to go to Germany but couldn’t take Phal with her without a passport, so she left him in Marseilles with enough money to take care of himself. Throughout the remainder of his life, he would attempt to write to Mme Farquenberg but was sadly never able to locate the lady who was so kind to the young Senegalese.

On his own in Marseilles, often working as a dishwasher among other menial jobs, he met Paul Latil, a boxing instructor who taught him how to crouch and deliver a proper punch. In 1912, at age 15, already with the build of a grown man, he had his first professional boxing fight, winning by knockout in the eighth round. He soon changed his name to Battling Siki as he felt white men could easily remember such a name.

Between 1912 and the breakout of World War 1 in 1914, he accumulated a record of 8 wins, 6 losses and 2 draws before enlisting in the French army as a 17 year old. Siki fought courageously for the French throughout the war in most of the major campaigns, performing heroic acts under heavy enemy fire which led to him becoming a highly decorated corporal that was awarded the Croix-de-Guerre and the Médaille Militaire for his courage in battle. He was in a regiment compiled mainly of whites and was the champion grenade thrower in his corps while with the colonials. He reportedly could launch a grenade 75 meters. He didn’t receive his first serious battle wounds until 1916 in the infamous “Battle Of The Somme” when bomb fragments went through both of his legs in the middle of the calf.

Rumors have him single handedly wiping out a machine gun nest full of German soldiers. In battle, he used what in boxing would become his trademark crouch that racist sports writers would later dub his “jungle crouch” as he snuck toward the German line where he launched grenades into trenches with wonderful aim. Conflicting reports have Siki successfully capturing nine German soldiers. One has a successful capture, while the other has Siki, worried that they will band together and charge at him, herd them into a shell hole where he quickly lobbed in a couple of grenades after them to do away with the risk.

While on a leave, Siki would mingle with nearby English corps’ as they regularly engaged in sport during downtime, namely boxing. He had a give and take battle with one of their men and was invited to stay for lunch where he was happy to eat a much better variety of food than what he was given by the French, this prompted him to continue boxing the Englishmen. From boxing the British soldiers, Siki learned sportsmanship. The Brits were not stylish boxers, but could absorb tremendous punishment, and dish it out too, which taught Siki how to take a punch. After the British soldiers were finished fighting a fellow, they would be friends again as it was all in sport, this led to Siki learning how to no longer take his anger at what transpired in the ring past the final bell.

Siki was honorably discharged from the French Army as a decorated soldier, and returned to Marseilles where he moved up from a pre war dishwasher to a post war waiter, a job he was given because the restaurant’s manager appreciated his service in the French Army. He continued to fight low level professional bouts. He made a bit of a reputation for himself as a boxer while mixing it up with the British soldiers, and was one day approached in his restaurant by a man while his hands were full of dishes who asked him if he would like to fight French Army champion Leon Derensy in Paris. Siki took the fight, and his manager allowed to him to take time off to train as he figured if his waiter got a name for himself as a boxer his restaurant would benefit from his fame. Siki knocked out Derensy in three rounds.

Even after this performance, he was going nowhere as a fighter. He lived to eat, drink, and smoke, and he used fighting as a means to afford these hobbies stating “In France I drink wine like a Frenchman, in Holland I drink beer like a Dutchman. Also, I smoke a good deal. When not training I like to be out with men smoking and talking and drinking.” Between the time of his discharge and the time he fought for the world light heavyweight title, Siki had fought 49 times with a record of 46-2-1, 21 KO’s, in those bouts. He spent time in the Netherlands where he fought a couple bouts, married a white woman, became a fan favorite, and spent time as a boxing instructor. During this impressive run, he held victories over top European fighters such as Harry Reeve and Marcel Nilles which earned him a shot at world famous light heavyweight champion Georges Carpentier who was the sporting hero of France.

Battling Siki would challenge Carpentier for his title on September 24, 1922. Georges Carpentier is regarded to this day as one of the greatest European fighters of all time. He had been successful against top tier fighters from welterweight all the way up to heavyweight, where he still packed a punch. He had movie star good looks, the demeanor of an absolute gentleman and fair sport, and immense popularity worldwide which was further bolstered by his highly publicized service in the French Army during World War 1 as a low flying observation pilot, often flying in harms way to carry out missions which, like Siki, earned him the distinction of being awarded the prestigious Croix de Guerre and the Médaille Militaire. He attracted droves of fans to the sport that would not typically be interested in prizefighting, but were excited to witness the squeaky clean celebrity war hero show off his pugilistic talents. A year earlier, as light heavyweight champion, Carpentier moved up in weight to face world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey in America, and such was his popularity that he was a major reason the bout generated boxing’s first million dollar gate. Dempsey, who reportedly dodged enlisting in the war effort, was actually cheered against by his fellow Americans who were hoping that the French war hero with the good looks, and the humble gentlemanly personality to match, would teach the infamous Manassa Mauler a lesson for being a coward in times of war.

Unfortunately for fans, and Carpentier, Dempsey was too good a big man for the former French welterweight, so Carpentier was overwhelmed and knocked out in the fourth round to the disappointment of fans everywhere. Prior to the Dempsey bout, Carpentier had traveled to the United States to face America’s Battling Levinsky for the world light heavyweight championship. Carpentier proved his worth in winning the title by fourth round knockout.

After losing to Dempsey at heavyweight, Carpentier returned to light heavyweight to defend his championship against all time great Ted “Kid” Lewis. Shockingly, Carpentier destroyed Lewis with a one punch knockout in the very first round. He then returned to France to defend his world title at home for the first time, which is when Battling Siki got the call to square off against the beloved celebrity hero of all of France in front of his adoring fans in Paris.

By the time they stepped into the ring in September of 1922, Carpentier was 28 years old with an outstanding record of 83-12-5, 52 KO’s, while Siki was 25 years old with a record of 49-9-3, 23 KO’s. Carpentier certainly had the edge in experience having fought Dempsey, Levinksy, and Lewis, while also facing formidable opposition in the form of Frank Klaus, Joe Jeannette, Billy Papke, Harry Lewis, and many others that were better than the very best men Siki had squared off with. Both Siki and Carpentier were roughly the same height, with Siki having a two inch reach advantage. Stylistically, Carpentier was a fine technical boxer with a powerful punch and blazing handspeed for a light heavyweight, while Siki fought out of a crouch and launched awkward and unorthodox attacks, at times reluctant, and at times relentless, but usually a difficult puzzle to solve.