Great article about the state of the hobby

It ran during the National and I'm sure some read it, but for those that didn't:

By Jeff Passan, Yahoo! Sports

July 28, 2006

Link to article

Jeff Passan

Yahoo! Sports

ANAHEIM, Calif. – I went to a baseball card show and a bling contest broke out.

In the right light, a refractor card may very well blind someone. There is more chrome on cards today than in the world's best-stocked rim shop. A guy is selling parallel cards on special, and it sounds like a great deal, if only I knew what a parallel card was.

I half-expect to see cards sprinkled with diamond dust.

"Good idea," Luther Wallace says.

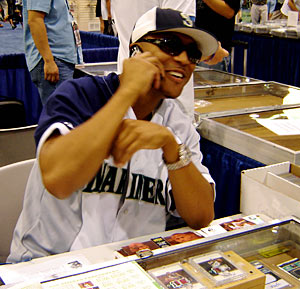

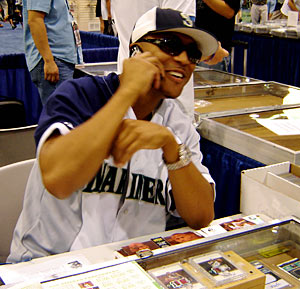

Wallace is manning a table in the middle of the Anaheim Convention Center. He's at the National Sports Collectors Convention, the world's biggest gathering of card and hobby enthusiasts, and since it's his first card show, he's hoping to make a splash with his collection of signed Felix Hernandez cards. Already Wallace is a well-known trader on eBay, going by Big Loot, which is the nickname he picked up during his four years in Washington-state prisons on weapons charges.

Loot says he's reformed now, out of the drug game and into the card game, which is likewise lucrative and much more legal. Baseball cards, the It hobby of the late 1980s and early '90s, have been reinvented from an industry built on mass collections to one of simple microeconomic principles: Limit supply and demand will spike. Prices have, too, thanks to the short-print-run subsets that include cards paired with jersey swatches and game-used bats and autographs and all sorts of gimmickry to justify charging, in some cases, hundreds of dollars per pack.

Luther Wallace, aka Big Loot, turned to dealing cards after doing a couple bids on weapons charges.

From that have emerged two markets: Older cards, which carry sentimentality as well as appreciated prices, and new ones, which in many cases make the old ones look like penny stocks next to Berkshire Hathaway. Though the fight isn't quite like the stats-vs.-scouts debate among baseball executives, there is some friendly jabbing. As Roger Burns, a dealer in pre-1941 cards, says: "I don't carry shiny stuff."

Yet there is enough interest in the shiny stuff to draw an expected 30,000 people through the weekend. While it pales to the reported 100,000 who graced the 1991 show in Anaheim, it proves that baseball cards are far from dead.

No, they've just changed, and for those who grew up during the card boom, it may well represent their first I'm-getting-old moment. I pointed to an autographed Hernandez card and asked how much.

"I want 25 for it," Loot says.

Not bad.

"But I'll take two," he says.

Two dollars? Deal.

"No, no," Loot says. "I meant $2,500. And I'll give it to you for $2,000."

Loot explains that it was one of 10 Hernandez cards signed with a red pen, which made it rarer than the ones signed in blue or green. And with a grade of 9.5 on a scale of 10, it was the highest graded out there, he claimed. And, well, forget Hernandez's ERA that has spent most of the season around 5. Scarcity took care of that little problem.

Limiting cards was the industry's direct response to a flaccid market, and while it worked in the short term, baseball cards' longer-term prospects are tenuous. The Donruss brand wasn't granted a license from the Major League Baseball Players' Association and isn't making baseball sets. Fleer, one of the big four companies, went broke. Topps, the granddaddy of trading-card companies, allowed three disgruntled shareholders, led by hedge-fund whiz Timothy Brog, to join its board Friday in what could be the first move toward a major front-office overhaul. Conventions have closed, stores have shuttered and still, the industry finds itself here, with 750 booths and young men such as Loot, 29, carrying around hundreds of thousands of dollars in merchandise.

"Excuse me," says a kid, no older than 10, drawing Loot's attention. "How much is that card?"

"Five thousand," Loot says.

The kid laughs, then walks away with his mom.

Before I got to the National, a card-collecting friend issued a warning.

"All those cards we grew up collecting," he said. "If you look in the Beckett, you won't see them. After four pages, it jumps to 1997."

He was right. Today's Beckett Baseball Card Monthly is a thorough compendium of the current market with barely a nod or wink to the past. Fifteen years ago, it was my bible. New issues arrived with all the promise of an oil well. If the price of a card I owned included an up arrow, I felt like I'd struck. I always wanted to write into their "Hot or Not" section and include Cleveland Indians reliever Rich Yett as "hot." Even though calling Yett pedestrian would be a compliment, his 1987 Topps card remains my favorite for its picture, which features Yett's resplendent blond mustache.

"Those were the good ol' days in the sense of simplicity," says Dr. James Beckett, the magazine's founder. "A lot of kids in my neighborhood did collect."

Baseball cards used to be about kids in the neighborhood – first flipping them or putting them in their spokes, then, spurred on by the proliferation of pricing guides such as Beckett's, buying them with a two-fold premise: enjoy them now and sell them later to pay for college.

The days of kids going to one another's house to trade cards are nearly extinct. Some have been priced out, others not interested in baseball.

"Whenever I was on a team, I would ask my teammates who their favorite player was," says Brad Petersen, a 13-year-old from Yorba Linda, Calif., attending the National with his father and two brothers. "I'd go home and get cards out and give it to them."

None of them started collecting. Which leaves Brad to talk cards with his dad, Larry, and his brothers Kevin, 11, and Luke, 10. Every two weeks, Brad gets his allowance. And he heads straight to his local card shop.

There, he scans the selection. Usually it's the same card, but he's got to look, just in case there's a new Derek Jeter. Along a wall, boxes overflowing with packs tantalize him. He wants to buy one with a jersey card, but for that price he could get plenty of inserts in packs that cost $1. It's the same question that has vexed kids for decades: What's the better risk?

Until the discontinuation of Donruss and Fleer, there were almost 100 sets and subsets. They had names like Absolute Memorabilia Tools of the Trade Swatch Single Jumbo Reverse. Topps and Upper Deck sell 40 types of cards today, some mass produced, most in limited numbers, which drives prices, Beckett said, "even if it's contrived."

Cognizant of the industry's direction, Beckett sold his company in January 2005 to a group headed by Peter Gudmundsson, now Beckett Media's CEO and president. Beckett had made a lot of men rich. He turned Mickey Mantle's 1952 Topps rookie from a valuable card into an industry icon. He kept raising the price of the 1909 T-206 Honus Wagner until it passed $1 million. Beckett loves baseball cards, old Roberto Clementes in particular, and can avert his eyes from today's sheen to see their substance.

"You'll always have the traditional thing," Beckett says. "Even in the show, you'll see it. It's the same-old, same-old, basic thing. You're putting cardboard with players on there."

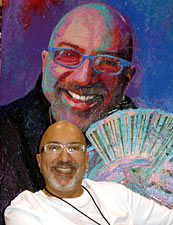

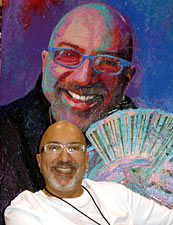

The only thing sheen coming from Alan Rosen's table is off his bald head. A few years ago, Mr. Mint, as he's called, finally gave up the ruse and went Bic. He looks great, and not just for a 60-year-old: With outlandish, if not stylish, glasses, an earring, a distinguished gray goatee, a white T-shirt and jeans, Rosen plays the big-money shark with a coolness that keeps his wife, Marnee, a busy woman.

"I'm an eighth-grade dropout … " Rosen starts a story.

"No you're not!" Marnee yells.

Alan Rosen, aka Mr. Mint, represents the old-school collector.

"Ninth."

"No."

"Tenth?" he says, getting a bit defensive.

"No," she says. "He's got his GED."

Whatever his education, Rosen's standing among his peers is unparalleled: He is considered among the most powerful dealers in the business. Over the first two days at the National, he has spent $83,000, and he's complaining it's been slow. He just bought a Johnny Bench rookie card, from an older couple who told him it was the only one in circulation graded a perfect 10, for $3,000. Minutes later, Rosen finds out there are six other 10s out there, so he finds a buyer and flips the card for $4,000. Fifteen minutes, $1,000 in Rosen's pocket.

For years he has worked like he's on speed. He scans each side of a Tom Seaver rookie card like a gemologist looping a diamond. He thinks fast, talks fast and does business fast. Money doesn't burn a hole in his pocket; it torches his whole pant leg. All of his ads include pictures of Rosen fanning out at least $10,000 in hundred-dollar bills.

"My motto: Flip, flip, flip," Rosen says. "If I buy, I'll sell. Unlike coins, stamps and Pogs, baseball relates to people 7 to 70. Because it's the American game, it will never go away, and this business never will, either."

Still, the direction of baseball cards disenchants him. He scans the room, looking for kids.

"There's one," he says, after a minute of looking, and there aren't any others in sight.

"You know why?" Rosen says. "When I was a kid, it was affordable to collect cards. Now it just costs $17.50 to get through the door here and $75 to buy a pack."

The debate on card companies' social responsibility – are they in business to create a huge market like commodities trading or to help promote the game of baseball to kids shying away from it? – is one without a definitive answer. Rosen entered as a hobby and saw it evolve into a business. Big Loot sells strictly for business, and he's so confident in the industry right now, he's taken on severe debt to finish his purchases.

For all their differences – Rosen doesn't deal in shiny stuff – he and Big Loot share the goal of making money, which still leaves the people who don't flip cards or float them on eBay but buy with the intent to hold.

"That's what this business is about," Rosen says. "Recapturing your past."

We called it the coin shop. I'm not sure why. About 5 percent of its inventory was coins. The rest was baseball cards.

For a kid, it was Mecca. Walk in and Ken, the mustachioed owner, gave warm greetings. Look at the new selection, he said, pointing to a few packs and a few new cards. Buy a box of this '90 Donruss. If it doesn't have a John Olerud rookie in it, he said, I'll give you one. What 10-year-old would turn down that deal?

I remember the first card I got. It was 1986, and Todd Worrell had won National League Rookie of the Year. His rookie cost $2. Sounded like a bargain, and when mom peeled off a pair of singles, I was hooked.

The next year, I got my first box. It was 1987 Topps. Heinous-looking cards – brown borders, funky lettering and awful pictures. What did I care? I had 36 packs to perfect the method of pulling out the gum, then piling the cards straight in my left hand and flicking them with a thumb to the waiting right hand. At 17 cards a pack, I practically doubled my collection.

Nothing could make the author happier than one last, glorious fling with an anonymous 1980s pitcher.

So it was with some surprise that as I meander around the convention center, I run into a man selling boxes of '87 Topps. I ask where they came from. He says he'd kept them in his garage for almost 20 years hoping to get rich. Cards from the '80s and early '90s have plummeted in price because of saturation. When '87 Topps came out, the per-pack price was 40 cents, and the dealer offers me the box for $15, meaning 19 years made him a 60-cent profit.

His bust is my bargain. I hadn't bought a pack of cards, let alone a box, in almost 15 years. I wonder why it had been so long, and as I tear open the first wax pack, I don't have a good answer.

Outgrowing baseball cards is natural, I guess, yet I'm completely drawn to the mystery that awaits inside every pack of baseball cards.

(And I'm not talking about the chewing gum, which I do try. As one may well imagine, gum is not scotch. With every chomp, the 19-year Topps Vintage disintegrates into fetid globules of sugar that curdle my taste buds and leaves an aftertaste of amalgamated dog breath and rotting corpse. The remaining 35 pieces are transported to a local hazmat center, where they are promptly destroyed.)

I wonder whether I will get a Barry Bonds or Bo Jackson rookie (I do, in pack Nos. 19 and 23, respectively). I am stunned to see a Julio Franco card and delighted to see the back of a Jose Canseco card stained – with wax instead of acne, but still. I learn, thanks to the information tidbits Topps used to include on the back of its cards, that Jeff Stone was one of 15 children, Howard Johnson was the co-winner of a rib-eating contest among professional athletes and Terry Mulholland worked as a gas-station attendant in the offseason. Presumably before he made $25 million over a 19-year career.

Satisfaction doesn't come until two packs remain. As I sort through the second-last pack, left to right, I get it. The Rich Yett card. No. 134. The one I really wanted. In Rich Yett's short career, which lasted 414 1/3 innings, I'm guessing the only people happier to see his face than me were hitters.

The card begs to be studied. Yett's mustache isn't as resplendent as I remembered. His hair, on the other hand, is classic: poofing out from under his hat and curled up, like a plant reaching for sunlight. Yett's jacket collar looks popped, and he seems in the midst of a deep thought.

Forget the Bonds and Bo and Rafael Palmeiro and Barry Larkin rookies. The card I really want is here, and while it's not the same as I remember, it's still great.

Which reminds me of something Jim Beckett said earlier: What a card is worth isn't always in the book. It's what you think it's worth.

Big Loot can take his Felix Hernandez cards. And Mr. Mint can take his million-dollar collection. They represent the new and the old. It's funny that the generation that collected cards from the middle of the boom is the one that went bust. Oh, well.

I'll take Rich Yett, whose card, according to Beckett is worth 5 cents. Cards like that, ones that are practically valueless, are called common. To me, it's anything but.

By Jeff Passan, Yahoo! Sports

July 28, 2006

Link to article

Jeff Passan

Yahoo! Sports

ANAHEIM, Calif. – I went to a baseball card show and a bling contest broke out.

In the right light, a refractor card may very well blind someone. There is more chrome on cards today than in the world's best-stocked rim shop. A guy is selling parallel cards on special, and it sounds like a great deal, if only I knew what a parallel card was.

I half-expect to see cards sprinkled with diamond dust.

"Good idea," Luther Wallace says.

Wallace is manning a table in the middle of the Anaheim Convention Center. He's at the National Sports Collectors Convention, the world's biggest gathering of card and hobby enthusiasts, and since it's his first card show, he's hoping to make a splash with his collection of signed Felix Hernandez cards. Already Wallace is a well-known trader on eBay, going by Big Loot, which is the nickname he picked up during his four years in Washington-state prisons on weapons charges.

Loot says he's reformed now, out of the drug game and into the card game, which is likewise lucrative and much more legal. Baseball cards, the It hobby of the late 1980s and early '90s, have been reinvented from an industry built on mass collections to one of simple microeconomic principles: Limit supply and demand will spike. Prices have, too, thanks to the short-print-run subsets that include cards paired with jersey swatches and game-used bats and autographs and all sorts of gimmickry to justify charging, in some cases, hundreds of dollars per pack.

Luther Wallace, aka Big Loot, turned to dealing cards after doing a couple bids on weapons charges.

From that have emerged two markets: Older cards, which carry sentimentality as well as appreciated prices, and new ones, which in many cases make the old ones look like penny stocks next to Berkshire Hathaway. Though the fight isn't quite like the stats-vs.-scouts debate among baseball executives, there is some friendly jabbing. As Roger Burns, a dealer in pre-1941 cards, says: "I don't carry shiny stuff."

Yet there is enough interest in the shiny stuff to draw an expected 30,000 people through the weekend. While it pales to the reported 100,000 who graced the 1991 show in Anaheim, it proves that baseball cards are far from dead.

No, they've just changed, and for those who grew up during the card boom, it may well represent their first I'm-getting-old moment. I pointed to an autographed Hernandez card and asked how much.

"I want 25 for it," Loot says.

Not bad.

"But I'll take two," he says.

Two dollars? Deal.

"No, no," Loot says. "I meant $2,500. And I'll give it to you for $2,000."

Loot explains that it was one of 10 Hernandez cards signed with a red pen, which made it rarer than the ones signed in blue or green. And with a grade of 9.5 on a scale of 10, it was the highest graded out there, he claimed. And, well, forget Hernandez's ERA that has spent most of the season around 5. Scarcity took care of that little problem.

Limiting cards was the industry's direct response to a flaccid market, and while it worked in the short term, baseball cards' longer-term prospects are tenuous. The Donruss brand wasn't granted a license from the Major League Baseball Players' Association and isn't making baseball sets. Fleer, one of the big four companies, went broke. Topps, the granddaddy of trading-card companies, allowed three disgruntled shareholders, led by hedge-fund whiz Timothy Brog, to join its board Friday in what could be the first move toward a major front-office overhaul. Conventions have closed, stores have shuttered and still, the industry finds itself here, with 750 booths and young men such as Loot, 29, carrying around hundreds of thousands of dollars in merchandise.

"Excuse me," says a kid, no older than 10, drawing Loot's attention. "How much is that card?"

"Five thousand," Loot says.

The kid laughs, then walks away with his mom.

Before I got to the National, a card-collecting friend issued a warning.

"All those cards we grew up collecting," he said. "If you look in the Beckett, you won't see them. After four pages, it jumps to 1997."

He was right. Today's Beckett Baseball Card Monthly is a thorough compendium of the current market with barely a nod or wink to the past. Fifteen years ago, it was my bible. New issues arrived with all the promise of an oil well. If the price of a card I owned included an up arrow, I felt like I'd struck. I always wanted to write into their "Hot or Not" section and include Cleveland Indians reliever Rich Yett as "hot." Even though calling Yett pedestrian would be a compliment, his 1987 Topps card remains my favorite for its picture, which features Yett's resplendent blond mustache.

"Those were the good ol' days in the sense of simplicity," says Dr. James Beckett, the magazine's founder. "A lot of kids in my neighborhood did collect."

Baseball cards used to be about kids in the neighborhood – first flipping them or putting them in their spokes, then, spurred on by the proliferation of pricing guides such as Beckett's, buying them with a two-fold premise: enjoy them now and sell them later to pay for college.

The days of kids going to one another's house to trade cards are nearly extinct. Some have been priced out, others not interested in baseball.

"Whenever I was on a team, I would ask my teammates who their favorite player was," says Brad Petersen, a 13-year-old from Yorba Linda, Calif., attending the National with his father and two brothers. "I'd go home and get cards out and give it to them."

None of them started collecting. Which leaves Brad to talk cards with his dad, Larry, and his brothers Kevin, 11, and Luke, 10. Every two weeks, Brad gets his allowance. And he heads straight to his local card shop.

There, he scans the selection. Usually it's the same card, but he's got to look, just in case there's a new Derek Jeter. Along a wall, boxes overflowing with packs tantalize him. He wants to buy one with a jersey card, but for that price he could get plenty of inserts in packs that cost $1. It's the same question that has vexed kids for decades: What's the better risk?

Until the discontinuation of Donruss and Fleer, there were almost 100 sets and subsets. They had names like Absolute Memorabilia Tools of the Trade Swatch Single Jumbo Reverse. Topps and Upper Deck sell 40 types of cards today, some mass produced, most in limited numbers, which drives prices, Beckett said, "even if it's contrived."

Cognizant of the industry's direction, Beckett sold his company in January 2005 to a group headed by Peter Gudmundsson, now Beckett Media's CEO and president. Beckett had made a lot of men rich. He turned Mickey Mantle's 1952 Topps rookie from a valuable card into an industry icon. He kept raising the price of the 1909 T-206 Honus Wagner until it passed $1 million. Beckett loves baseball cards, old Roberto Clementes in particular, and can avert his eyes from today's sheen to see their substance.

"You'll always have the traditional thing," Beckett says. "Even in the show, you'll see it. It's the same-old, same-old, basic thing. You're putting cardboard with players on there."

The only thing sheen coming from Alan Rosen's table is off his bald head. A few years ago, Mr. Mint, as he's called, finally gave up the ruse and went Bic. He looks great, and not just for a 60-year-old: With outlandish, if not stylish, glasses, an earring, a distinguished gray goatee, a white T-shirt and jeans, Rosen plays the big-money shark with a coolness that keeps his wife, Marnee, a busy woman.

"I'm an eighth-grade dropout … " Rosen starts a story.

"No you're not!" Marnee yells.

Alan Rosen, aka Mr. Mint, represents the old-school collector.

"Ninth."

"No."

"Tenth?" he says, getting a bit defensive.

"No," she says. "He's got his GED."

Whatever his education, Rosen's standing among his peers is unparalleled: He is considered among the most powerful dealers in the business. Over the first two days at the National, he has spent $83,000, and he's complaining it's been slow. He just bought a Johnny Bench rookie card, from an older couple who told him it was the only one in circulation graded a perfect 10, for $3,000. Minutes later, Rosen finds out there are six other 10s out there, so he finds a buyer and flips the card for $4,000. Fifteen minutes, $1,000 in Rosen's pocket.

For years he has worked like he's on speed. He scans each side of a Tom Seaver rookie card like a gemologist looping a diamond. He thinks fast, talks fast and does business fast. Money doesn't burn a hole in his pocket; it torches his whole pant leg. All of his ads include pictures of Rosen fanning out at least $10,000 in hundred-dollar bills.

"My motto: Flip, flip, flip," Rosen says. "If I buy, I'll sell. Unlike coins, stamps and Pogs, baseball relates to people 7 to 70. Because it's the American game, it will never go away, and this business never will, either."

Still, the direction of baseball cards disenchants him. He scans the room, looking for kids.

"There's one," he says, after a minute of looking, and there aren't any others in sight.

"You know why?" Rosen says. "When I was a kid, it was affordable to collect cards. Now it just costs $17.50 to get through the door here and $75 to buy a pack."

The debate on card companies' social responsibility – are they in business to create a huge market like commodities trading or to help promote the game of baseball to kids shying away from it? – is one without a definitive answer. Rosen entered as a hobby and saw it evolve into a business. Big Loot sells strictly for business, and he's so confident in the industry right now, he's taken on severe debt to finish his purchases.

For all their differences – Rosen doesn't deal in shiny stuff – he and Big Loot share the goal of making money, which still leaves the people who don't flip cards or float them on eBay but buy with the intent to hold.

"That's what this business is about," Rosen says. "Recapturing your past."

We called it the coin shop. I'm not sure why. About 5 percent of its inventory was coins. The rest was baseball cards.

For a kid, it was Mecca. Walk in and Ken, the mustachioed owner, gave warm greetings. Look at the new selection, he said, pointing to a few packs and a few new cards. Buy a box of this '90 Donruss. If it doesn't have a John Olerud rookie in it, he said, I'll give you one. What 10-year-old would turn down that deal?

I remember the first card I got. It was 1986, and Todd Worrell had won National League Rookie of the Year. His rookie cost $2. Sounded like a bargain, and when mom peeled off a pair of singles, I was hooked.

The next year, I got my first box. It was 1987 Topps. Heinous-looking cards – brown borders, funky lettering and awful pictures. What did I care? I had 36 packs to perfect the method of pulling out the gum, then piling the cards straight in my left hand and flicking them with a thumb to the waiting right hand. At 17 cards a pack, I practically doubled my collection.

Nothing could make the author happier than one last, glorious fling with an anonymous 1980s pitcher.

So it was with some surprise that as I meander around the convention center, I run into a man selling boxes of '87 Topps. I ask where they came from. He says he'd kept them in his garage for almost 20 years hoping to get rich. Cards from the '80s and early '90s have plummeted in price because of saturation. When '87 Topps came out, the per-pack price was 40 cents, and the dealer offers me the box for $15, meaning 19 years made him a 60-cent profit.

His bust is my bargain. I hadn't bought a pack of cards, let alone a box, in almost 15 years. I wonder why it had been so long, and as I tear open the first wax pack, I don't have a good answer.

Outgrowing baseball cards is natural, I guess, yet I'm completely drawn to the mystery that awaits inside every pack of baseball cards.

(And I'm not talking about the chewing gum, which I do try. As one may well imagine, gum is not scotch. With every chomp, the 19-year Topps Vintage disintegrates into fetid globules of sugar that curdle my taste buds and leaves an aftertaste of amalgamated dog breath and rotting corpse. The remaining 35 pieces are transported to a local hazmat center, where they are promptly destroyed.)

I wonder whether I will get a Barry Bonds or Bo Jackson rookie (I do, in pack Nos. 19 and 23, respectively). I am stunned to see a Julio Franco card and delighted to see the back of a Jose Canseco card stained – with wax instead of acne, but still. I learn, thanks to the information tidbits Topps used to include on the back of its cards, that Jeff Stone was one of 15 children, Howard Johnson was the co-winner of a rib-eating contest among professional athletes and Terry Mulholland worked as a gas-station attendant in the offseason. Presumably before he made $25 million over a 19-year career.

Satisfaction doesn't come until two packs remain. As I sort through the second-last pack, left to right, I get it. The Rich Yett card. No. 134. The one I really wanted. In Rich Yett's short career, which lasted 414 1/3 innings, I'm guessing the only people happier to see his face than me were hitters.

The card begs to be studied. Yett's mustache isn't as resplendent as I remembered. His hair, on the other hand, is classic: poofing out from under his hat and curled up, like a plant reaching for sunlight. Yett's jacket collar looks popped, and he seems in the midst of a deep thought.

Forget the Bonds and Bo and Rafael Palmeiro and Barry Larkin rookies. The card I really want is here, and while it's not the same as I remember, it's still great.

Which reminds me of something Jim Beckett said earlier: What a card is worth isn't always in the book. It's what you think it's worth.

Big Loot can take his Felix Hernandez cards. And Mr. Mint can take his million-dollar collection. They represent the new and the old. It's funny that the generation that collected cards from the middle of the boom is the one that went bust. Oh, well.

I'll take Rich Yett, whose card, according to Beckett is worth 5 cents. Cards like that, ones that are practically valueless, are called common. To me, it's anything but.

GO MARLINS! Home of the best fans in baseball!!

0

Comments

Shane

Joe

GO MARLINS! Home of the best fans in baseball!!

<< <i>The only thing sheen coming from Alan Rosen's table is off his bald head >>

Thanx DaBig for sharing.

I do like the 'shiny' stuff tho.

mike