Secret Marks on coins? Serious inquiry.

Insider2

Posts: 14,452 ✭✭✭✭✭

Insider2

Posts: 14,452 ✭✭✭✭✭

Several 19th Century Banknote companies added "secret marks" to the dies for the stamps they produced. IMHO, I believe it would not be out of line to suggest that the U.S. Mint did something as that to deter counterfeiters. What do you think? Do you have an example we can discuss?

PS "Secret marks" put on a specific die (1875 1c) are excluded from this poll.

Secret Marks on coins? Serious inquiry.

This is a private poll: no-one will see what you voted for.

0

Comments

I guess this one is not a secret, anymore

I forgot all about that one! It qualifies. Hopefully, now we can stick to genuine US issues.

Weren't all of the old dies made by hand.

The whole thing is a secret mark...Right???

My Saint Set

For most US issues I don't believe that the quality is consistent enough for the mint to try to use "secret marks".

I know that the RCM uses a hologram sort of mark on bullion (and maybe high value circulating?) coins to deter counterfeiters, but it is a not a secret.

Early capped bust halves have a notched point on S-13, supposedly to denote a die personally prepared by John Reich.

I said "No", to the specific question about entire series, since I think it would be pretty hard to keep a secret for all these years! Too many people poking around the archives, and staring at coins through 10X loupes.

Now, there are specific dies that had marks placed on them, for who knows why.

Example: The Large and Small dot 1884(?) Morgan Dollars, and some of the examples posted before me, and probably after me.

I don't think any were anti-counterfeit measures, however.

I've heard this story. Did you know that other coins (all the way into the 20th Century) have a notched star? Reich was dead.

Thanks, but they fall into the group that is excluded from my question.

I know it’s done on diamond but not coins

Anyone else think the Omega Man's mark is more of an "ankh" ( ☥ ) than an "omega" ( Ω ) ?

--Severian the Lame

I thought they are serial #'s on the diamond's girdle. Therefore not a secret.

The Philadelphia Mint altered a working 1-cent die in 1872 [correction - 1875] so they could have evidence of an employee's petty theft of coins. Available letters do not say more than that the change was tiny and on the reverse. There could have been other instances.

Some Eisenhower dollar fans see gold equipment on the moon (reverse). However, All I;ve ever seen is the only example of a "coin mooning people."

The Philadelphia Mint altered a working 1-cent die in 1872 [correction - 1875] so they could have evidence of an employee's petty theft of coins. Available letters do not say more than that the change was tiny and on the reverse. There could have been other instances.

Some Eisenhower dollar fans see golf equipment on the moon (reverse). However, All I;ve ever seen is the only example of a "coin mooning people."

I keep hearing something about changes to an 1872 one cent die.

This does not pertain to the discussion.

I'm looking for an unnecessary and insignificant mark of some kind that is on all the coins of the same design during a period of issue that would probably be missed by a counterfeiter and be small enough not to transfer easily. That "Omega" mark would qualify If it were on a genuine product of the Mint."

IMO, the broken star is one. I believe there are others yet to be discussed. After a while I may post some.

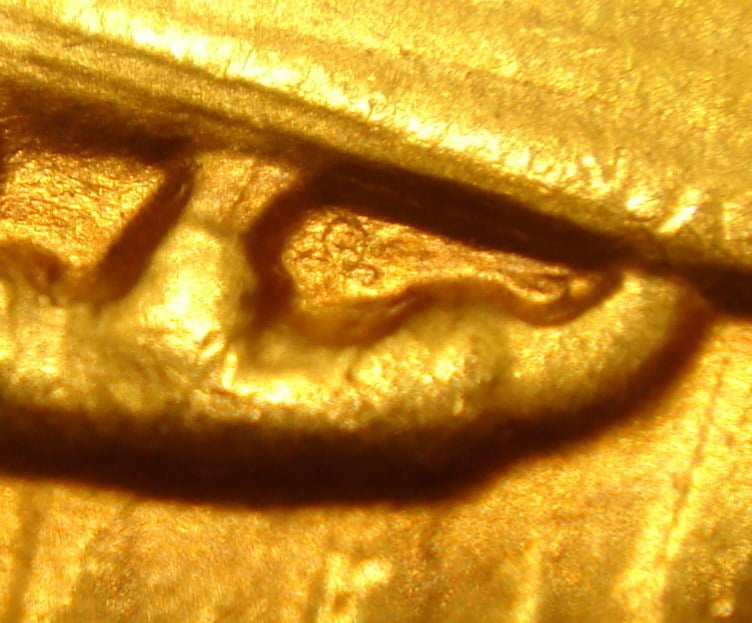

Is this an "R?" Both upside down and upright. A "stylized" JR?

@insider2, will respond back Friday with much more info. I have commitments to finish today.

These engravings are incuse on the coins, so they were done on the working hubs inside the clasp, by John Reich, on six different instances. The examples shown are from a 1808 $5 (my coin), and an 1807 .50.

The clasp engravings pictured here are reverse images, or how Reich would observe these on the working dies. The coins show the opposite, which appear to be a random engraving (they are not random, JR engraved this small but precise design on four different denominations, in a different rotation on each). Also, JR engraved this design on the 1807, 1809, and 1812 half dollar hub changes (which totals six different instances).

For the early US Mint during the years 1793-1823, Chief Engraver Robert Scot would have authority on any "secret marks" that were engraved on hubbs/dies to deter counterfeiters.

Scot had much previous experience in anti-counterfeiting efforts. The history of this begins in Scotland, Robert Scot's place of birth. Within Great Britain, the Scottish public had considerably more confidence in banknotes than England, and Scotland had greater success in deterring counterfeiters. In the period of 1806-1825 there were 8 executions in Scotland for counterfeiting, and in England over 300 counterfeiters were executed.

The high quality of the engraving was the best deterrent against banknote fakes. The most prominent of Scottish banknote engravers, James Kirkwood, was described in New Picture of Edinburgh in 1806 "This gentleman (bred a watchmaker) conceived an ardent passion for Ornamental Writing, in the engraving of which he soon outstripped all the regular bred artists. For neatness, correctness, and freedom he has seldom been equaled."

When Scot sailed to the colony of Virginia by 1775, he began engraving Virginia currency. In 1776, Scot engraved the radical Virginia Seal on currency notes, depicting the ousting of the monarchy from the newly declared United States. Scot boldly engraved "Death to Counterfeit" on Virginia currency. While few counterfeiters in the early US were executed, many had their ears cropped and a "C" branded on their foreheads at the town pillory. Scot's 1776 Virginia note below shows the overlapping roundhand script and Gothic lettering, similar to the "Ornamental Writing" of Scottish banknotes:

Robert Scot was paid the large sum of 2103 pounds, 8 shillings in 1780 by Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson for "His Services and expenses in detecting some persons concerning in counterfeiting the paper currency." (Journals of the State of Virginia, Volume II). This was a generous amount of money that probably covered a period of at least two years.

The early US Mint had a "Castaing" style edge lettering and rimming machining, almost from inception. This was a complex machine that took many years to develop in Europe, to fabricate one that quickly in the US would have required some instruction, which was given in Dobson's Encyclopedia in Volume 5 and illustrated in Plate CXLIV engraved by Robert Scot in 1792 (can post image on request). The purpose of the edge milling "machine" was described, "by the invention of impressions on the edges, that admirable expedient for preventing the alteration of the species, is carried to the utmost perfection." (Dobson's Volume 5, page 131).

President Washington and Secretary of State Jefferson subscribed to Dobson's Encyclopedia, and Mint Director Rittenhouse was a contributor. No doubt Rittenhouse read the "Coining" article, published at the time of Mint inception, and he certainly would want this rimming machine for the new US coinage. The Mint's rimming machine thus had several purposes, stating the denomination (.50 and $1), thickening the edge for better striking and stacking, deterring clipping or alteration, and making counterfeiting much more difficult, as this machine could not be easily duplicated by counterfeiters. Some of the symbols engraved by Scot on the edge dies have yet to be deciphered. Even today, deceptive modern fakes can be identified by the edges. So in a way, the edge lettering and symbols, engraved by Scot, were "secret marks" to deter counterfeiters.

4

Regarding the scalloped 13th star that Reich engraved, this was for all of the silver and gold denominations on each obverse working die. This began upon Reich's employment on 4-1-1807, and abruptly ended upon his resignation ten years later on 3-31-1817 - with two blatant exceptions - Scot accidently used a scalloped star punch on one dime die and one half eagle die, then corrected this and used un-notched star punches on all subsequent working dies. Reich's scalloped star punch was obviously to mark dies that he finished, and a recent JRJ article proves this by dentil counts. While probably not the primary objective, the notched 13th star could be used as a marker to identify fakes without this feature. Many contemporary counterfeits were so crude they could be easily identified without these marks, but some were quite deceptive.

5

To understand the engraving designs within the clasps on my first post, some explanation and examples are needed from Robert Scot's earlier assistant engravers. Scot was the initial engraver for Dobson's Encyclopedia, and with over 500 copperplate engravings expected, Scot advertised locally and nationally for engraving help. Samuel Allardice was the first of four apprentices to be hired, in 1790. Allardice engraved tiny hidden initials on several engravings. What Scot did next was unique in American engraving, he allowed all of his apprentices to place their initials under Scot's signature on engravings they assisted with, and then full signatures when they became journeymen engravers. When Scot was appointed Engraver to the Mint on 11-23-1793, Scot made Allardice partner, with subsequent engravings signed Scot & Allardice until they disbanded in 1796 (Scot did only very limited copperplate engraving after his Mint appointment).

An example of hidden initials by Samuel Allardice. Can you find them? Then an example of where Allardice placed his initials below Scot's signature. From my collection of Dobson's Encyclopedia:

Which brings us to the US Mint clasp engravings by John Reich:

These engraving designs are within the clasp on capped bust dimes, half dollars, quarter eagles, and half eagles. They consist of three graver cuts, an open-ended loop with one end shorter than the other, and two short slanted cuts on each end. Since they are incuse on struck coins, they had to have been engraved on the hubb, as engraving on the original or working dies would result in a raised engraving in relief. They can only be fully observed on well struck, high grade coins.

This clasp design was engraved by John Reich on these obverse hubbs:

1807 Capped Bust half dollar

1807 Capped Bust half eagle $5

1808 Capped Bust quarter eagle $2.50

1809 Capped Bust dime

1809 Capped Bust half dollar new hubb

1812 Capped Bust half dollar new hubb

1817 Capped Bust half dollar new hubb (Reich or Scot? Shows fine hair and lower relief of Scot)

All of these clasp engravings were the same design, but with different rotation within the clasp. As we say at my work on CATIA models, it is a "design in space" that can be rotated about. Quite ingenious of Reich.

John Reich had previously engraved his initial R on medal engravings, as his father had done.

When observed on a coin, this design appears random, without any identifiable letter or number. When the image of a coin is reversed, or a mirror image, the image is the same as Reich would observe on the working die. This resulting image appears as a distinct "R" and when inverted 180 degrees, a less distinct "J" appears. The "R" is similar to contemporary R engravings used at that time (will post if requested).

Did John Reich engrave a covert monogram of his initials, JR? As assistant engraver, did Reich want to be credited in the future for engravings that he completed, and not the chief engraver?

Scot would not allow initials on a coin, but did he authorize initials on working dies, that would be illegible on coins?

Or were they just random squiggles?

Scot knew very well of the clasp design, as he retained them for half dollar and dime usage until his death in 1823. The next chief engraver, William Kneass, also knew of this design, as he removed it when he modified the Capped Bust half dollar to his design in 1834!

Covert monograms were popular at the time including printers William Young, Joseph Bumstead, Thomas Collier, and Bennett Wheeler.

Another clue comes with the Capped Bust quarter introduction of 1815. John Reich also engraved a tiny design on this clasp, but it was completely different than his previous clasp design. At first glance, it looks like a random squiggle, but when rotated in orientation, it appears to be a script "M". Why would Reich engrave an M? Was it for his middle name, Matthaus?

I doubt if the primary intent of the clasp engraving was for counterfeit detection, although they would be difficult to reproduce by a counterfeiter.

When lined up in a row they are very impressive (1807 .50, 1815 .25, 1807 .50 inverted):

Johann Matthaus Reich

Great read. Thanks

Fascinating. Post so I can come back to this.

Large Cent collector Homer Downing marked his lettered edge coins by white inking the H and D in HUNDRED to prove his ownership.

Interesting comments about Reich.

RE: "The early US Mint had a "Castaing" style edge lettering and rimming machining, almost from inception. This was a complex machine that took many years to develop in Europe,"

I have to question this statement. The edge lettering machine for blanks was very simple to build and operate. Most were made in Europe by blacksmiths and gear makers - basic mechanics. The same wedge principle was used in metal forming in the 16th century. Blondeau's version different only cosmetically from larger geared forms used in Sweden in 1706. Patents of that period were largely worthless since anyone could patent the same invention multiple times and there was no determination of "inventiveness."

The Mint edge lettering and rimming machine was a precision machine with tight tolerances, capable of fine adjustment, and repeatable for a million or more cycles - a loosely fit machine would simply not work.

With those requirements, having worked within tooling and equipment for 33 years, if one of those machines were custom built today (not off the shelf), a minimum of a 4 month design/build would be needed - seven months or more would be more typical for that size/complexity - and that is with CNC machinery. There would be hand work to get to a fine (~32) finish, heat treating, assembly, fitting - not that simple of a process. When tolerances get tight, the fabrication time increases.

With the machine technology in the US in 1792, it is amazing to me they had fabricated, or procured, a machine that soon. Here is a description published in Philadelphia on March 10, 1792 (my collection):

Now you understand just how good those old guys were. As a former mfg engineer, I don't believe there are any machinists alive today that could match their work.

Back in the late 80's when I was working in an aircraft bearing factory, we were taking pre-WWI machine lathes and updating them because they were so solidly built we couldn't buy the quality in modern machinery at a reasonable cost. We'd refit with hand-fit bearings and our own tooling to get 1 micron accuracy.

Let me know if you're gonna be at Baltimore. I have a pair of dice 1.5" square made out of solid hardened steel, probably as an "apprentice's piece" circa 1930. The faces are so parallel and square to each other, you can barely see light when you stack them. I've measured and they're within .0005 of each other. Freakin' amazing work.