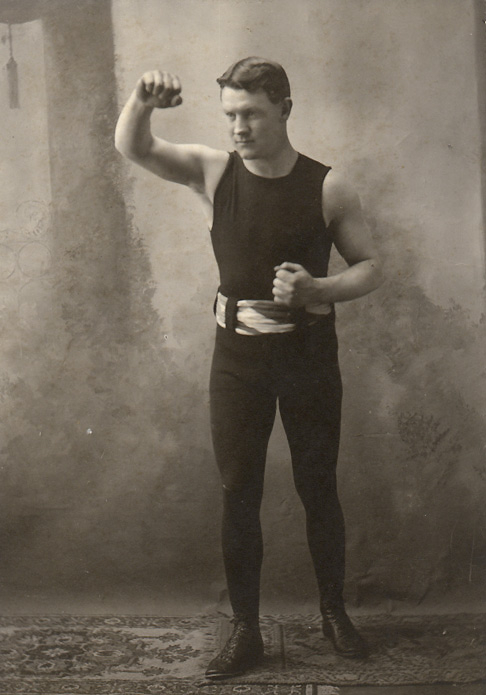

This is Johnny Coulon in his prime, during his fighting days. He was involved in boxing for his entire life.

Coulon, also called "The Cherry Picker of Logan Square," began boxing at only 8-years-old and trained under his father, Pop Coulon. Later he trained with Elbows McFadden, George Siddons and James Corbett. His early boxing experience helped him become one of the youngest title claimants of all time at 18, when he defeated Kid Murphy for a portion of the bantamweight title.

A two-fisted slugger, Johnny Coulon turned pro in 1905 just three weeks before his 16th birthday. He was born in Toronto, Canada but for most of his life he resided in Chicago.

Coulon won his first 26 bouts before losing a 10-round decision to Kid Murphy. In a rematch with Murphy in 1908, Coulon reversed the decision and earned recognition as the American bantamweight champion.

On March 6, 1910, Coulon captured the vacant world bantamweight crown when he defeated England's Jim Kendrick in 19 rounds. He defended the title against Earl Denning, Frankie Conley, Frankie Burns and Kid Williams. He finally lost the crown in 1914 when Williams stopped him in the third round.

There was eventually no question as to the strength of his claim and he held the championship until 1914, when it was said he was well past his best and had been weakened by illness.

But Coulon was a skilled and scientific fighter, and he later opened Coulon's Gymnasium with his wife in Chicago, with fighters like "Sugar" Ray Robinson, Joe Louis and Carmen Basilio training there on occasion. Coulon even became one of the first ever former world champions to officially handle a current champion when he trained the great Eddie Perkins.

Throughout his life, Coulon stayed in shape. "I have never drank of smoked and I try to instill this in the boys, not by preaching but by just talking, and it seems to go over."

Coulon served in the U.S. Army during World War I, often instructing soldiers on how to fight. He boxed twice after his service stint and retired from the ring in 1920.

On his 72nd birthday, Coulon showed off for reporters by walking around the gym on his hands, it was similar to his "unliftable man" trick, he liked to show off his various tricks and skills .

When Coulon died at 84-years-old in 1973, he took an encyclopedia of boxing knowledge with him.

''The toughest opponent is me. A Iot of times, you don't want to train. You don't want to box. Sometimes, life hits you to the point where you don't even want to live. You have to fight with that person. You have to make yourself wake up in the morning. You have to make yourself watch your weight. That's how I fight with that person.'' - OIeksandr Usyk

Prime George Foreman at his most frightening, as he clubs Joe King Roman senseless.

Foreman made his first defense of the heavyweight championship with a brutal and cruel 1st round KO of Joe King Roman at Nippon Budokan in Tokyo, Japan in 1973.

Roman, a Puerto Rican heavyweight who fought out of Florida, was no match for Foreman. When Roman tried to move early, Foreman cut off the ring and trapped him near the ropes. A left hook caught Roman on the temple and sent him down into the ropes quite awkwardly, and Foreman then caught Roman with a right hand as he was down (pictured).

Action stopped as Roman's corner protested, but their fighter claimed to be okay, the referee ruled no foul was committed and Foreman appeared somewhat apologetic. When the fight resumed, a whirling right hand caught Roman and knocked him flat. He beat the count only to be caught with a few more punches, punctuated by an uppercut that crumbled him to the canvas, all but unconscious, where he was counted out.

William Rothwell, known as "Young Corbett II", early 1900s featherweight champion and Hall of Famer. It's a fascinating story, Young Corbett II pulled off a massive upset on this day in 1901 when he KO'd "Terrible" Terry McGovern in Round 2 of their fight in Hartford, Connecticut, to win the world featherweight crown. It's fascinating because Terry McGovern was one of the most feared fighters in boxing history, they didn't call him "Terrible" for nothing, he left a trail of destruction across two divisions on his way to the top of the bantamweight and featherweight mountains. Terry McGovern's reputation is well known to boxing fans, he was the Mike Tyson of his era. His ring record is littered with bodies, he was one of the hardest punchers in the history of the featherweight division and one of the most violent men to ever step foot in the ring. To say he was feared during his time would be an understatement. By 1901 McGovern had seized the bantamweight and featherweight titles by brute force, and was thought of as being invincible or damn near it. Enter Young Corbett II, he was from Denver, Colorado, and though Young Corbett had registered victories over former champion George Dixon and contender Oscar Gardner, he wasn't a well-known pugilist and wasn't given much of a chance to defeat the supposedly invincible featherweight kingpin, Terry McGovern. Corbett, who was trying to prove that he was by no means intimidated of McGovern's reputation, banged on the McGovern's dressing room door before their fight and jeered him by reciting some nasty remarks and insulting him. Now that takes some serious guts, and is one of the boldest things I've ever heard of, can you imagine someone busting through the door of prime Mike Tyson's locker room and taunting him before a fight? But Corbett did exactly that, then proceeded to back it up in the ring by knocking Terry McGovern out. The crowd was was absolutely stunned. It's insane to pull something like that off one time, but in the rematch in 1903, Corbett stopped him in 11, proving the first time wasn't a fluke.

Young Corbett II in his prime

Hall of Fame Athletes / 1978 Inductees / Young Corbett

Young Corbett, Denver’s first and only world boxing champion, was inducted into the Colorado Sports Hall of Fame posthumously in 1978 after gaining national fame and becoming a hometown hero in Denver.

The recognition by his native state seems long overdue and comes after he took his place among the ring immortals by being elected to the Boxing Hall of Fame in 1965.

Corbett received national attention when he knocked out “Terrible” Terry McGovern in the second round of a featherweight title fight in Hartford, Connecticut, November 28, 1901.

William H. Rothwell was born in Denver, October 4, 1880. It was on Swansea Street that he first learning to protect himself by using his fists. When he started fighting professionally at the tender age of seventeen, he took his ring name after his manager, Jimmy Corbett. Boxing was popular in the rip-roaring mining towns of Colorado and Corbett had several fights in such towns as Leadville, Cripple Creek and Aspen.

Standing only five-feet two-inches tall, he gained acclaim as a deadly puncher. In a memorable fight in Denver, he stopped Oscar Garner in the second round and then beat Kid Broad and ex-champion George Dixon.

After his forty-second fight, Manager Corbett figured the time had come to take his protégé east, and a title bout with Terry McGovern was negotiated. It was considered a mismatch by most eastern critics, as McGovern was viewed, pound for pound, one of the deadliest punchers in the boxing game. In the previous two years he had scored seventeen knockouts, including a string of twelve straight.

The betting gentry wagered the feisty twenty-one year old from the Rockies would take the count within five rounds. Although the featherweight limit was 122 pounds at the time, by mutual agreement the fighters agreed to scale in at 126 pounds. It was a slam-bang battle from the opening bell. Corbett ripped over a right to the jaw late in the first round and the champ went down but jumped up without a count.

Early in the second round another right to the jaw floored McGovern, but again he leaped to his feat without taking a count. The champion fought back, but Corbett refused to give ground, landing a vicious uppercut to the champ’s jaw and McGovern landed on his back and was counted out. A new champion was born.

Corbett’s victory touched off a wild celebration back home in Denver, and Corbett’s mother, two sisters and younger brother were the focus of national attention.

Unfortunately, Corbett’s fame was short lived. Unable to make his weight, he had to relinquish his featherweight title. Abe Attell, who fought many of his early fights in Denver, was recognized as the featherweight champion.

Corbett campaigned as a lightweight with moderate success, then returned to Denver for his last fight against Kid Broad in 1902. Corbett began instructing youngsters and retired in 1910 with a record of thirty-four knockouts in 104 fights.

Corbett died in April, 1927, only a few months after he had appeared in an exhibition at the Elks Club against Mike Mongone, an opponent in his early days in the mining camps.

This is another photo of Terry McGovern (left) and Young Corbett II before their 1901 fight, my god, look at Young Corbett II, he's built like a damn tree trunk.

On March 31, 1903, at Mechanics Pavilion in San Francisco the rematch between McGovern and Corbett II took place, it was a violent fight, and Corbett knocked out McGovern in the 11th round, as was the case in their first fight, the finishing blow was an uppercut. There was controversy, the controversy stemmed from claims that McGovern might have been the victim of a faulty referee's count, though the fight result of Corbett winning by knockout in the 11th round is generally accepted.

"William Rothwell, better known as Young Corbett of Denver, showed decisively tonight that his victory over Terry McGovern of Brooklyn at Hartford a year ago was no fluke by defeating McGovern in the 11th round after a fight in which there was not a second of idleness for either man. In nearly every round Corbett, fighting like a machine, never overlooking an opportunity to send home his blows, had a shade the better of the argument, and when finally in the 11th round he got the Brooklyn boy fairly going he never let up on him, until Terry sank to the floor a badly defeated man. There was some question as to whether or not McGovern was down at the count of 10. McGovern tried to get up and was on his feet an instant after the timekeeper counted him out. As it was, it was nearly a minute after McGovern had been carried to his corner before he was able to sit up and understand what had happened." - The Boston Post

McGovern was also down once each in the first two rounds. The ring was momentarily invaded by McGovern supporters who believed McGovern had beaten the count, but the police immediately piled them through the ropes and restored order. Post fight comments:

"The final blow was a right uppercut to the jaw that put McGovern to the floor for the full count. Even had he been able to regain his feet before the count of 10 I would have had him out, as he was absolutely unable to defend himself." -Young Corbett II

"It was the greatest robbery in the history of the prize ring. I had Corbett beaten from start to finish. I landed on him when and where I pleased and surely would have had him out within a few rounds. I was not knocked out, but admit that the right uppercut to the chin dazed me and I took the count in order to save myself." -Terry McGovern

Like I said, "Terrible" Terry McGovern was no joke. He was an Irishman from Brooklyn, New York, they called him "The Brooklyn Terror", he struck fear in hearts of his opponents and up until he met his kryptonite in Young Corbett II, McGovern was a wrecking machine.

“Terrible” Terry McGovern

By: Monte D. Cox

The name Terry McGovern might not mean much to boxing fans today, but in his youthful prime he was one of the most awesome hitters in boxing history. His punching power put fear into the hearts of fighters from bantamweight to lightweight. McGovern was like a little Mike Tyson destroying opponent after opponent during his short, but devastating reign of terror.

Stylistically there are many similarities between Terry McGovern and Mike Tyson. Both were stocky built, swarming style hitters who came in low and wrecked their opponents with sharp and powerful counter punches. Like Tyson, McGovern had a seek and destroy mentality from the opening round.

Prior to the coming of Terry McGovern fans did not like to watch fights that ended almost as soon as they began. The boxing crowd and the gamblers who ran the sport liked to see drawn out boxing exhibitions that featured sparring for openings, masterful defense, and a relatively slow pace until an opponent made a mistake. The longer a fight went the more money that could be placed on bets by the gamblers and the fighter’s financial backers. It was common to see the elite fighters carry an opponent to cash in on the stakes. McGovern cared nothing for that. He came out of his corner like a hungry lion who was ready to feed and attempted to devour his opponents in the shortest amount of time. When McGovern exploded on the scene he electrified the crowds with his fast attacks and devastating, shocking early round knockouts. No one had seen anything quite like him before. McGovern scored 23 of his 44 career knockouts in 3 rounds or less.

The National Police Gazette characterized him thusly; “Terry’s style of fighting was a never ending source of delight to the thousands who saw him for the first time in a ring engagement. He was as fast as a streak of lightning, and the large crowd was amazed at his great footwork…Terry has wonderful control of himself in a mix-up and never gets rattled. He would go in like a steam engine and slip away like a snake. This was one of the most notable features of his work in the contest. He was always fighting but never let his opponent hit him to any extent.”

McGovern was a hand held high, ducking, slipping, and short armed puncher much like heavyweight Tyson. “Iron” Mike was known for his defense, slipping and countering to get inside. McGovern fought much in the same manner, the Gazette reported, “McGovern’s defense was perfect and his delivery fast and furious.”

After his fight with Billy Rotchford the Gazette described McGovern with the following, “He hooks fast and punches straight and has a remarkably swift punch, moving over the shortest possible space, and both hands are capable of working evenly, smooth and fast as two pistons. The position in which he had his mitts drew up his shoulder and protected his chin and neck. The elbows were ready to drop to stave off rib blows, and the hand, either right or left, prepared to slip inside any swing or wide hook an opponent might deal up.”

When Tyson was “on” he was a strong body puncher as in the Jesse Ferguson fight, but Tyson was never the pound for pound puncher to the body that McGovern was. Historian Barry Deskins wrote, “Short blows to the body followed by a viscous straight right is McGovern’s strongest asset, particularly his work to the body.” Old time fight announcer Joe Humphrey’s said, Sept 1936 Ring Magazine, “McGovern was a lightning fast feinter and a terrible hitter. He was a great body puncher, an art that seems to be lost to the present generation.”

Harry Lenny, an old time fighter and trainer who served as a sparring partner for lightweight champion Joe Gans and worked Joe Louis corner agrees with this assessment saying, “McGovern was a very powerful man, who hurt you with every punch. He was a great body puncher.”

Ducking and going to the body with quick two handed combinations McGovern would then come up with a powerful right to the head. The Gazette writer depicted McGovern in his fight with Casper Leon as having “a beautiful right hand cross-counter punch” that lands with “such marvelous force that something has to drop, and that something usually lays stretched out until the referee counts the fateful ten.”

When Terry McGovern challenged champion Pedlar Palmer for the bantamweight championship the boxing public expected a great boxer versus puncher match up. Instead they saw an annihilation. Like Tyson’s 1988 knockout of the previously undefeated Mike Spinks, McGovern’s 1899 knockout of previously unbeaten Palmer ended in the first round. McGovern stunned the crowd with a terrifying right hand to the chin that won the championship in record time. McGovern was just 19 years old.

George Dixon, one of the greatest fighters of all time, reigned as Featherweight champion for nearly 10 years and made 23 successful title defenses. His boxing skills were so highly regarded he was considered to be “a fighter without a flaw” during his prime years. Although Dixon was past his peak and wearing down from a long career he had never been knocked off his feet in a regulation match. McGovern gave him no respect attacking him with the same ferocity as he did all of his other opponent’s. McGovern laid a beating on Dixon taking away his title and sending him to the canvas twice in the 8th and final round. McGovern was now the world featherweight boxing champion and he was not done yet.

“Unconquered and unconquerable Terry McGovern, the Brooklyn whirlwind fighter, stands today without a peer in the pugilistic world” wrote the Gazette after McGovern defeated lightweight champion Frank Erne in a non-title match. McGovern vanquished Erne in three rounds. In the space of 10 months he had defeated the bantamweight, featherweight, and lightweight world champions all by knockout. At one point he had knocked out 10 men in a total of 17 rounds and the victims included highly ranked contenders Pat Haley and Harry Forbes.

Like Tyson after him McGovern was considered an invincible puncher who could not be beat. Terrible Terry’s reign of terror over the lower weight classes ended when he was upset and beaten by Young Corbett. The Gazette wrote, “McGovern for the first time in his career, met an opponent who was not afraid of him, and a clear headed, strong, quick and shifty boxer who had a tremendous punch.” Corbett had won the battle of psychological warfare by incensing McGovern and causing him to lose his cool. Before the fight he went by McGovern’s dressing room and yelled, “Come on out you Irish Rat, and take the licking of your life.”

McGovern charged at Corbett during the opening bell but didn’t cover up and left himself wide open. Corbett landed a strong right hand counter that put McGovern on his pants. McGovern came back and decked Corbett the same round but he was making mistakes. In the second round Corbett again caught McGovern coming in wildly and knocked him down for the second time and soon finished him. Corbett also beat McGovern a rematch stopping him in 11 rounds to prove it was no fluke.

Neither McGovern nor Tyson were quite the same once their aura of invincibility was removed.

McGovern after being bested began to suffer from mental problems. He spent much of his later life institutionalized. Francis Albertanti, writer for The Ring Magazine and witness to hundreds of live fights, wrote in 1928, “We may never live to see a duplicate of the famous ‘Terrible Terry’. Fighters like McGovern come once in a lifetime.”

This is the definitive article about Terry McGovern and his reign of terror.

PART I

The All-Time Great Bantamweights: No 2. Terry McGovern 65-6-7 (44 KOs)

The early days of gloved boxing was the Wild West era, where Wyatt Earp refereed a prizefight and the sport was still outlawed in many states.

The leading gunslinger of these years did not draw his irons in the wild west, but the east.

Irish-American Terry McGovern, Brooklynite, terror of every weight class from bantamweight to lightweight, ruled boxing at the turn of the 20th century. His reign was not a lengthy one, but his ring record is littered with bodies, the lack of surviving footage sparing our desensitised 21st-century eyes from possibly the most violent man to ever step foot in the ring.

It was a time of precocious fencers and unhinged madmen. McGovern fought them all.

A Natural Fighter

Before he would be given the moniker of ‘Terrible’, young Terry McGovern first had to find his way into the prize ring. He donned gloves and traded punches out of necessity. Fatherless at ten and having to support his mother and young siblings, McGovern did not go to school, instead working as a gardener. A report from ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ written at the height of McGovern’s prime in 1899, looked back to his start in the prize ring, which seemed to be a hunt for more money and a better life for his family than McGovern could earn elsewhere:

"Two years ago a sturdy, modest little fellow, with hands as callous as an elephant’s hide, walked into Schiellein’s Assembly Rooms in New York, where an amateur boxing tournament was billed to take place, and informed the managers of the affair that he wished to try for a prize in the bantam weight class. He came unheralded, unsought, and unknown. There was nothing about his general appearance which struck the managers as unusual, except that his fame was what we commonly term sturdy. Whether boxing is a lowly calling or not does not detract one whit from the credit that is due to the young fellow, who was Terry McGovern. That was the name of the boy - the same lad who won a ten dollar prize in the aforesaid tournament by knocking out four other aspirants. In two short years this mere boy has leaped from obscurity into the lime light of fame and fortune."

McGovern did fight in an amateur tournament even after his first pro bout, but if the exact details of his start in the game are lost to history or at best hidden below the surface, the first known bout for McGovern was a perfect indication of the unbridled violence to come. Seventeen years old, 110lbs, little Terry McGovern fought fellow novice Johnny Snee. Nothing is known of Snee, other than his profile being a bloody mess when McGovern got his mitts on him. In what was a one-sided routing, McGovern’s eagerness to dish out violence was also his downfall, thrown out for dirty work in the third round when trying to put his man to sleep. A few weeks later McGovern went ten rounds against an opponent who came in overweight. Terry spotted him the pounds and beat him up anyway. A sign of things to come.

McGovern being disqualified for sheer savagery is the only time he lost in his first four years in the ring. His record in this time? 55-2-4, a champion at two weights and a force of nature so hostile he smashed the best lightweights in the world with as much ease as he did the bantams.

It’s those bantamweights that are of most concern to us here. And as we’ll see, also the featherweights.

American Bantam

All reports of McGovern’s early bouts sing from the same hymn sheet. McGovern’s song was not that of a graceful choir, but of pounding heavy metal; a marauding, non-stop pressure fighter who had only one intention - to knock his opponent out.

Tommy Sullivan

The only man to push McGovern close in his early fights was undefeated Tommy Sullivan. Described as ‘bantams’ but fought at the modern flyweight limit, this bout does nothing for McGovern’s ranking here but it is insightful all the same, as Sullivan would in time would become world featherweight champion, destroying Abe Attell in five rounds. A draw was as good as anyone managed against McGovern, lest he get himself disqualified for rough housing.

Draws and disqualifications featured in McGovern’s first rivalry. Philadelphia native Tim Callahan was a shifty type, a talented boxer, and in a trilogy fought over four months in 1898, McGovern’s burgeoning talent and unparalleled ferocity can be accurately traced.

McGovern lost the first, although as previously stated he was never legitimately beaten in this time. Fought at 114lbs - bantamweights in this era but below the threshold designated for this list - McGovern got much the better of the fight but was warned frequently for striking Callahan in the clinch.

The rules called for one arm to be free in the clinch, so McGovern’s tactics were likely above board. But he continued with the tactic and was thrown out in the 11th, Callahan victor by disqualification.

This is where reports differ on their interpretation of what transpired; ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ said McGovern "seemed to lose his head" and "repeated the offense".

‘The New York Press’ saw it differently. McGovern had been "fighting fiercely in short range" when the referee stopped the bout. Contrary to the ‘Daily Eagle’ report, when McGovern was thrown out he had not been bending the rules; McGovern was punching freely with both hands. The same paper said that McGovern had "got the worst of a bad decision".

Not that Callahan was a mediocre fighter, something he proved when they clashed again a few months later. ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ was impressed with Callahan, calling him a "quick, shifty and hard fighter" who knew "all the tricks of the trade". He must have been good as he extended McGovern the full 15 at 115lbs, and the bout was declared a draw.

Callahan had been on a decent run since coming to New York. Whatever we make of his first bout with McGovern, he was skilled enough to survive him for 15 rounds afterward, and had also fought solid contender George Munroe twice before his third meeting with McGovern.

Munroe would mix in top class for much of his career, and had fought McGovern thrice in 1898 as well, disqualified once, going 20 rounds to a draw in another, and to no surprise also being knocked out.

Callahan was not the puncher McGovern was, but in his first fight with Munroe he gave "one of the prettiest exhibitions of scientific boxing seen", and the crowd - albeit a small one - were aghast when a draw was announced after 20 rounds. Callahan was a defensive stylist, who ducked punches well and had ‘fast foot work’. Callahan was not just a cutie though; in the late rounds he came forward and ‘administered severe punishment’ to Munroe. In their October rematch, Callahan won a rightful 20-round decision, and set himself up well for another go with McGovern.

McGovern was 0-1-1 with Callahan at this point, even if the loss was an unjust call. The third bout showed McGovern as Callahan’s superior. The weights are not known at this point and may never be, but seeing as they had previously fought at the (then) bantam limit of 115lbs it is likely that they met there again, or perhaps a pound above or below.

What is clear to see is the beating Callahan suffered at McGovern’s brick fists. Also apparent is McGovern’s technical mastery of Callahan.

Shifty Tim Callahan

Callahan did all the leading early on, but McGovern "cleverly blocked" his punches. It was a fast competitive fight from start to finish, and in the eighth round McGovern found the measure of his man and started walking him down. In the ninth McGovern had Callahan groggy from "repeated smashes on the ribs and kidneys". In the tenth and final round, McGovern dropped Callahan twice, the second time from a right hand upstairs set up by a jab to the body. McGovern reads not just as a ferocious pressure fighter but also an intelligent one.

This series is also impressive as Callahan would go on to become a fighter of some repute, beating many first-raters. McGovern stopping him is also an indicator of his class as Callahan would not be knocked out for another decade, then a veteran of at least 140 pro bouts who had seen better days.

After seeing rid of Callahan, McGovern would fight nothing but the best men the lower weights had to offer.

Harry Forbes was perhaps the best of McGovern’s opponents on his run to the championship. A boxer from Chicago, Forbes earned respect from the New York pressmen with his speedy and smart showings in the big apple. He had not been a prizefighter for long, but was credited for his "splendid work" by ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’.

Forbes was good enough that many patrons allegedly lost money on him, for McGovern knocked him out in the 15th round in a "fast and scientific" bout. Forbes would return, with more experience and plaudits to his name. McGovern would be waiting for him.

Austin Rice had drawn with Tim Callahan, ‘Torpedo’ Billy Murphy, George Munroe, and even the hard-punching Oscar Gardener. After fighting McGovern he would go on to beat George Dixon, Tommy Sullivan, Callahan, and would even fight for the world crown at featherweight. He was a top battler in his day and still in his prime when he signed to fight McGovern.

They fought on New Year's Eve, and McGovern ended an excellent 1898 campaign by stopping Rice. But McGovern’s aggression was nearly his undoing. ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ saw McGovern as a consummate ring general, setting Rice up for big right hands which had him sprawling, and although McGovern had issues landing his left early, he also stopped Rice from landing with his own.

Austin Rice

In the 11th, McGovern was dropped, a rare misstep; "he grew careless in his anxiety to win quickly" according to ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ and - although under duress - Rice still had his wits about him to time a right hand to the jaw which sat McGovern down. McGovern rallied, continuing with the clever work he had shown earlier in the bout, and Rice was forced to quit before the 15th round could begin.

McGovern wanted to square up with Jimmy Barry, who held a title claim which was either called ‘Paperweight’ or ‘Bantamweight’, a title he defended anywhere between 105-110lbs, although he had also taken on fighters closer to McGovern’s weight. A fight between Barry and McGovern had been arranged before but never came off, and Barry might have been reluctant to meet the surging New Yorker. He sat out the rest of the year, fighting only once more and retiring undefeated.

McGovern had to be content with Casper Leon, a previous Jimmy Barry challenger. He’d gone 20 rounds with the champ, and was coming off a win over ‘Torpedo’ Billy Murphy, another excellent contender of the time.

Casper Leon

Leon, an Italian born Gaspare Leoni - and known as the ‘Sicilian Swordfish’ - was a naturally smaller man, a modern flyweight, but he was an experienced fighter who had gone the championship distance and claimed the American bantamweight title. ‘The Sun’ (New York paper) called it "an important bantam weight match". McGovern barely squeezed into the 115lbs limit, perhaps a sign of things to come, but he blasted Leon in 12 rounds; a body assault softening Leon up, a left "on the point of the jaw" flattening him for the count.

‘The New York Evening Telegram’ said that McGovern "so clearly outclassed Leon that no question will be raised for some time about the great superiority of this fiery little chap". The ‘New York Journal and Advertiser’ noted that Leon’s boxing skills had kept him in the fight (with McGovern taking "a good jabbing") but that the larger man had never faltered in his task.

‘The New York Morning Telegraph’ called McGovern "the best 115 pound boxer in the world" and said he "had the fight well in hand from the first tap of the gong to the finish". The same report credited Leon as a "clever Italian" who made "a strong and determined defense, and never flinched till the last". Leon had landed well with jabs and right hands at times, but McGovern "paid no more attention to them than though they had been snowflakes". ‘The New York World’ said that after this knockout McGovern was "the peer of any man of his weight in the world". ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ said that Leon was "one of the cleverest boys in the division" and observed that he took several minutes to recover from the knockout blow. Despite the size difference, this was an impressive win over an accomplished fighter.

McGovern did not rest on these plaudits; he fought in each month from January through July. In March he fought Patsy Haley, a legit bantam who had once fought at 118lbs in a bout billed as being for the ‘world’ title. The gold standard for little men at this point in time - at least in Britain - was the clever Pedlar Palmer. Haley was said to be far below that standard by British writers after his 20-round loss to Will Curley (another promising British bantam) but was said to be "undoubtedly clever" and a "shifty boxer".

So Haley had missed out on a lucrative fight with Palmer, but was still a contender of note. His recent results included draws with Oscar Gardner, Tommy Sullivan and Johnny Ritchie, all world-class fighters.

Fought at 116lbs and scheduled for 25 rounds, McGovern demonstrated his excellence in comparison to his peers. ‘The Daily Eagle’ wrote:

"By knocking out Patsy Haley of Buffalo last night at the Lenox Athletic Club (McGovern) accomplished what Oscar Gardner failed to do in twenty rounds and what took Dave Sullivan twenty-three rounds of the hardest kind of work to do. Haley acknowledged before the exhibition began that he was never in better condition in his life."

The same report said Haley had made "a good showing", and that "his clever foot work saved him several times".

McGovern was not as quick as Haley, but his blows carried more weight and he placed his shots well. McGovern relentlessly pressured Haley, and in the 18th he finished him off with a blistering combination: left to the body, left upstairs, then a "crushing right hook on the jaw" that deemed a count unnecessary. ‘The New York Wold’ said that McGovern "shot his right over and Patsy fell like a log". The same report noted that McGovern had feigned grogginess to try and trick Haley at times, but the Buffalo man was shrewd and did not fall for any of McGovern’s traps. McGovern’s aggressiveness was necessary as Haley tried to box and survive.

In April, McGovern spotted featherweight contender Joe Bernstein around eight pounds. Bernstein was not a big puncher, but his added weight and experience against the best men around meant that McGovern was up against it. ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ called McGovern "the hardest hitting man of his weight and inches in the world" prior to the bout.

Bernstein was clever and precise, and shook McGovern up in the fifth with a shot around the ear. McGovern fought back though and "cut loose with a vengeance", Bernstein’s successes being few and far between as the fight progressed. The bigger man’s high guard forced McGovern to target the body, which of course he was comfortable doing. In the final round, McGovern "at last succeeded in getting over his right" and Bernstein staggered to the ropes. Bernstein’s guile saw him through, with McGovern a worthy winner after 25 hard rounds.

Featherweight Joe Bernstein

Men of McGovern’s poundage struggled to withstand his punches.

Although his record shows little in the way of knockouts, Sammy Kelly carried his dig late into the fight and stopped a few notable fighters. Kelly had stopped Austin Rice, gone 20 rounds with Jimmy Barry and in his prior bout had matched Oscar Gardner at 116lbs, fighting gamely before before stopped in 14. His best win was over the excellent Englishman Billy Plimmer back in 1897, Kelly crossing the Atlantic to knock out the Brummy battler in the 20th round in a bout advertised as being for the ‘world’ title at 115lbs.

"Terry McGovern’s ability to hold the bantamweight championship will be tested when he meets Sammy Kelly on Friday night", said ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’. "Kelly has not fought since his memorable battle with Oscar Gardner and has completely recovered from the broken rib he received on that occasion. He says the long rest has been an incalculable benefit to him and he is stronger now than he ever has been."

Sammy Kelly

Kelly had taken interest in McGovern’s previous bouts and considered him an easy out. McGovern showed he was anything but, with Kelly holding on for dear life from the outset, clearly bothered by McGovern’s hits about the wind. Following the usual pattern of his bouts, once his opponent was worried about the shots to the body, he raised his aim, sparking Kelly with a right hand in the fifth round.

"The fight was not that interesting," wrote ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’, "but showed that Terry is a good boy for many others to keep away from."

Billy Barrett was reportedly a former amateur standout, and was in somewhat of a purple patch. Unbeaten in eight fights including wins over Patsy Haley and George Munroe, Barrett had also fought (and lost) to the excellent Harry Forbes, and lasted ten rounds with McGovern when he was still a novice.

McGovern was a novice no more, and Barrett "developed one of the most brilliant streaks of yellow imaginable" and "laid down like a whipped dog" when McGovern landed a strong punch in the tenth. No weights were announced but Barrett usually fought men of McGovern’s size, so this was likely a bantamweight contest.

Chiacago bantam Johnny Ritchie had struggled with some of the best bantams he faced (notably Eddie Sprague and Harry Forbes) but had made some noise with his recent victories, including a ten-round decision win over Patsy Haley. He was one of many excellent operators in the lower weights that fought out of ‘The Windy City’, chief among them Jimmy Barry, whom had defeated Ritchie over six rounds a year prior. Ritchie was game, and was styled as the ‘Western’ bantam champ.

Before the fight, the terms were announced in the ring: 118lbs, for "the bantamweight championship". This is presumably the national title, as it was then announced that the winner would face Pedlar Palmer for the world championship.

‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ deemed Ritchie a "clever boy", and noted his strong effort in the first two rounds. However, the same publication observed a look of fear just not on Ritchie’s face, but in his work. McGovern installed this fear into his opponents, the certainty of a beating turning competent fighters into cowards.

Johnny Ritchie, Chicago contender

In the first round Ritchie landed good lefts on McGovern’s face and the New Yorker couldn’t land with his own counters, so presumably Ritchie was out-jabbing him. Ritchie was credited for clever parrying of McGovern’s punches. In typical fashion, McGovern rushed Ritchie and started landing first about the gut and then to the face. The Chicago boy looked "amazed at McGovern’s aggressiveness". Ritchie recomposed himself, landing a stiff jab to end the first.

In the second McGovern set about his man, backing him up to the ropes and landing effectively. Ritchie showed cleverness in getting back to a more favourable position, and landed with a one-two that was clean but did little to hold McGovern off. McGovern showed "no respect" for Ritchie’s offense and dropped him near the end of the round. Ritchie was up immediately and clinched his way through the end of the round to survive.

Ritchie should have remained in his corner, for in the third round McGovern annihilated him. The Irish-American did not waste any time feinting or jabbing with Ritchie but simply ran after him, giving him no room to escape lest he climb through the ropes. McGovern was "flushed with excitement", but Ritchie "showed great cleverness" in avoiding some dangerous looking blows.

In close, Ritchie could not handle McGovern, who hit him in the clinch and generally ragged him around the ring. Ritchie tried hard, but he was ready for his bed, a right hand knocking him half asleep and a follow-up left sending him into dreamland.

‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ summarised McGovern’s devastating power punches thus:

"The blow which accomplished the trick was a left hand hook on the point of the jaw. It was delivered with lightning speed and crushing force. Nothing human could stand before that blow and breathe comfortably, and Ritchie, being made of flesh and blood turned turtle and fell on the floor upon his face."

If this article reads as "and then McGovern knocked this guy out, and this guy out, and then he beat this contender up", it’s because in his prime this is what he did. Consider him a lower weight Mike Tyson; a flame that burnt at its brightest briefly, but in that time scorched anyone who got close to it.

McGovern had battered the best bantams the United States of America could offer up. But there was an majestic boxer in the land of tea and scones who figured to be his biggest test.

The World Bantamweight Champion

"To the intense astonishment of most present, and the consternation of many, the long-looked forward to contest between the renowned Billy Plimmer and Pedlar Palmer, which was decided last night, resulted in complete defeat of the accomplished Birmingham boxer at the hands of the clever Canning Town youth."

Pedlar Palmer, legendary English boxer

Young Londoner Pedlar Palmer was respected before he fought Billy Plimmer, with a win over respected little battler Walter Croot an early highlight of his career. But his complete domination of a fighter who was likely one of the best lower weight fighters in the world marked him as a fighter of not just high quality, but of high stature among the writers of the day.

'Sporting Life’ was not just astonished at Palmer’s victory, but the way he went about it.

Palmer was not only "quicker and cleverer" than Plimmer - something "that many good judges thought impossible" - but his speed and ring smarts had "not been seen for years".

Plimmer was regarded by some as the ‘champion bantam’ of the world, and had been to the States, gaining respect on the other side of the pond for his four-round decision win over the great George Dixon, then respected as one of the best men in the world regardless of weight and the king of the featherweights. This bout was over a short distance, but still, Plimmer was held in high regard after it. Before and after his fight with Dixon he was generally regarded as one of the smartest fighters in the world.

Billy Plimmer

Palmer however, just 19 years old, dominated Plimmer from the start. In the 14th the Birmingham man was disqualified when his seconds rushed the ring to save him from further punishment, ostensibly a corner stoppage. He’d had enough.

Within a month Palmer had crossed the sea to fight Dixon, one in which he matched Dixon for cleverness but likely got bested in, the fight ruled a draw after six. No shame.

After this Palmer did nothing but win, beating quality fighters from Britain, Ireland and America, among them undefeated Irishman (via Boston) Dave Sullivan (20-round decision) who would go on to win the lineal featherweight title; unbeaten Billy Rotchford from Chicago (DQ in the third round, Palmer looked to be a class above); and Plimmer again (16th round KO, two right hand socks to the jaw flattening the Birmingham man) were other notable victories the Canning Town youth accrued.

American Johnny Murphy, who had been 40 rounds with George Dixon and held the accomplished Ike ‘Spider’ Weir to a draw, was no more successful at combating Palmer’s skill set than anyone else. He was extremely game, but at the end of 20 rounds ‘The Sportsman’ felt Palmer would "reign supreme for many years" as bantam champion.

The National Sporting Club in England recognised Palmer as the world champ at bantam, his claim following him up in weight from the modern flyweight limit to 116lbs. Boxrec has Palmer at 26-0-1 when he traveled to New York to fight McGovern, but it is likely he fought in many more bouts. All reports of the time refer to him as being undefeated. He was 23 years old to McGovern’s 19. Both were undoubtedly in their prime fighting years.

The 16 September 1899 edition of the 'Illustrated Police Budget’ published a preview of the fight which gives us a better picture of Palmer’s style:

"Two more dissimilar styles in boxing could not possibly be imagined than those employed by Palmer and McGovern. The former is one of the trickiest little fellows that has ever put up a hand. Quick and agile as a cat, he is here, there and everywhere, putting into execution more dodges and expedients than any two ordinary men. He is termed the 'box of tricks', and certainly no name could fit him better. His head work is simply marvellous, and very frequently he has been known not to attempt to defend himself with his arms at all, but to stand up to his opponent and dodge the blows solely by the wonderful rapidity with which he would manipulate his little head piece. His foot-work too, is a perfect study and these two factors, when added to the great ability he is possessed of in the handling of his 'dukes' have made him what he is, a veritable champion." So for his day, Palmer was a prototypical Nicolino Locche (or for a comparative defensive wizard from his own era, Australian featherweight legend Young Griffo) who would use his supernatural reflexes and fine judging of distance to slip punches effortlessly.

Training reports of Palmer sound like he and his team were ahead of their time: rather than lengthy jogs, short bursts of sprints punctuated his long walks, perhaps to replicate the flurries he would try to land in a 20-round fight. Weights, rope and bag work also made up his regime.

‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ wrote of McGovern’s meteoric rise, his penchant for knocking contenders stiff, and of his standing as favourite for the upcoming clash. They also noted that Palmer was likely to be his stiffest test:

"Should an opponent clinch then is the time Terry is most dangerous. With both hands working like trip hammers and hitting a blow almost as hard as a lightweights he soon has his opponent so anxious about avoiding further punishment on the body that he leaves the opening for the head, which Terry is always looking for, and then with left or right, as occasion demands, comes the blow which cuts short the timekeeper’s work. In Palmer, however, Terry is to meet the hardest proposition of his career. The English lad knows all the tricks of the game and is a thorough master of all the fine points. He is wonderfully strong and fast on his legs and a past master with the left hand and confidently believes that McGovern will be no harder than some of the men he has already disposed of. Palmer hopes to tire Terry with his rapid foot work and with a good use of his left wear the Brooklyn boy down and finally find the opening for his right."

McGovern saw the bout the same way, but also felt his own cleverness would be a factor:

"Even if Palmer does get the opportunity to land some smart blows on me, I am not even then so certain that they will hit me where they will do much harm, for I have made it a practice to avoid blows by ducking my head and otherwise dodging without using my hands, so as to have them immediately available for the purpose of doing some offensive work at the slightest opportunity. I have managed to attain considerable cleverness in this dodging work and, as a rule, receive the blows on the back of my neck or some such harmless place. As I can hit equally hard with either hand, it makes no difference to me on which side the opening comes or which fist lands the blows." Despite McGovern’s claims of cleverness, it was seen as a scientific artist of the prize ring versus a savage, a throwback even in these wild, violent years.

The fight was well publicised. As well as lots of column inches being taken up discussing the particulars, both men also refereed bouts on the same card to drum up local interest. Palmer also came out and gave a speech, in which he thanked the Americans for the warm reception he had received.

They would be fighting for a $10,000 purse, an astronomical figure for the time and said to be the biggest purse to date for bantamweights by contemporary sources. This would be around $300,000 today; a large purse for modern bantamweights! They would also get a cut of the receipts from the motion picture, still a big deal in these days.

The crowd in Tuckahoe, New York would have to wait to see how the clash of styles would play out, as the fight was postponed due to rain. Both men had already made weight and started to rehydrate when the decision was made. It was said that McGovern would find it much harder to come back down to the 116lbs championship limit.

The wire report was thus delayed, and the British faithful would have to wait for news of how their boy got on. Some had made the trip over, "with plenty of money to wager" according to New York newspaper ‘The Sun’. These would be very well off fans of pugilism; the majority would have to wait for the result to be printed in the papers.

Palmer’s message to his fans back home was relayed in the ‘Illustrated Police Budget’:

"They tell me that McGovern is a bit mustard: but they must not forget that I am also a trifle ‘Coleman’s’ when I am on the job, and you can bet I am going for it this time. So that if I am whacked it will be by a corking good lad."

Palmer was indeed whacked, in what remains to this day one of the more astounding results in boxing history.

McGovern came down flanked by his seconds, one holding the Stars & Stripes aloft, the other the Irish tricolour. Palmer proudly displayed a Union Jack. The downpour of the day before was gone, and the sun made it a beautiful day according to more than one source.

Pedlar Palmer’s day was about to be darkened

Palmer and McGovern, as they might have looked squaring up

The first round was almost cut short by an over enthusiastic timekeeper halfway through. McGovern didn’t need the rest of it.

"McGovern outclassed Palmer" read the ‘New York World’ report. "The fight was so one-sided that it is almost impossible to see how Palmer, though the best boy in England, ever could have expected to win. McGovern was quicker, stronger, and by far the more intelligent of the two."

And clearly more savage. Palmer was first affected by McGovern’s feared body punching. He went down early, one report makes it seem innocuous enough, perhaps a case of tangled feet, perhaps a punch-cum-shove. But when he wasn’t landing hard, McGovern skipped in and out of range. The same ‘World’ report said that McGovern was "the equal of Jim Corbett in clever footwork, getting in and out of hitting distance like magic".

First blood to the brawler then; wholly capable of jousting with the supposed master boxer.

McGovern used those slips and feints he described before the fight to get close to the Londoner, then he ripped left and rights to the ribs. Palmer was in a lot of discomfort.

When the timekeeper first rang the bell (he accidentally dropped his hammer) both boys went back to their corners. McGovern was smiling. Palmer could be forgiven for thinking the round was over given that it must have seemed like an eternity.

Within five seconds the referee had noticed the time keeper's mistake and rushed both boys back to centre ring. Palmer tried to fight back, landing a few short blows to McGovern’s own ribs, but saw "most of them go wild and only strike the boy’s shoulder". McGovern’s underrated defence again.

Palmer went for broke, swinging a big right hand at McGovern, who slipped it and slammed a short left hook into the champion's jaw. Palmer went down in a heap, but jumped up at the count of three, rushing McGovern, trying anything to keep his undefeated record intact.

"He hears nothing, sees nothing but that mocking grin on the brown face of the Brooklyn lad. In he dashes, caution thrown to the winds, both hands flying in swings, ducking his head curiously and awkwardly from side to side. Terry blocks him and waits his chance."

Palmer was desperate. McGovern capitalised; a left hook to the body bringing Palmer’s guard down, and a short right hook upstairs felling him again. Palmer swayed forward, whirled around and toppled over.

Two minutes and 33 seconds was all it took for McGovern to become the true world bantamweight champ. Legendary heavyweight John L. Sullivan stormed the ring and congratulated him. The crowd went crazy and the local sheriff had to calm a lot of rowdy spectators down. New York paper ‘The Sun’ said the 8,000 spectators were dumbfounded about the result. It was the first world title bout under Queensbury Rules to end in a first-round knockout.

"I knocked Palmer out several rounds earlier than I expected to," said the new champion, "but I felt sure I would do it sooner or later. I

went in looking for a hard fight, and came out the winner, without a scratch, after fighting less than three minutes. Some are already speaking of an accidental blow. There was no accident about this."

The former title claimant was in damage control mode, as many fighters are when they are defeated. He also contradicted himself so blatantly that McGovern’s blows must have scrambled his senses:

"My being knocked out by McGovern was to some extent an accident. The fight was perfectly fair, and I lost. The blow was fair too, and it was a clean knockout, the first one that ever came to me. But two minutes and forty seconds of fighting does not give a correct idea of our respective abilities."

To the contrary, I would argue that it perfectly encapsulated McGovern’s abilities.

"McGovern’s great fight", read the headline in ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’, likening its local boy to "John L.Sullivan in miniature".

At this time Sullivan - the former heavyweight champion - was still seen by many to be the greatest pugilist that had ever lived. The same article labelled his fans ‘Gowanusians’ and said they were "firmly convinced he can beat Jeffries"; a tongue-in-cheek remark referring to James J. Jeffries, the current heavyweight champion and then seen as the best active fighter in the world.

McGovern’s pound-for-pound prowess cannot be understated: cartoons of the time showed bodies behind him and the greats of the era lined up in front of him, spooked, getting larger and larger down the line, including the likes of fellow pound-for-pound terror Bob Fitzsimmons. These were humorous depictions, but telling: McGovern’s ability to wreak havoc was not bound by weight.

The Chicago Daily Tribune, 4th February, 1900 showing the bodies behind McGovern

McGovern was so confident of beating Palmer he had not only bet on himself, he had made arrangements to fight for the world featherweight title just a few months after.

But the now ‘world’ bantamweight champ would still manage to drub a few more quality fighters before he challenged for a second world championship.

McGovern fought all-comers, beating two opponents in one night in Ohio ("the hardest puncher ever seen in the local ring "according to one report) and in Chicago, including Patsy Haley again, this time inside of one round.

He also fought Billy Rotchford, the Chicago bantam who had been the distance with the great Jimmy Barry and lost via disqualification to Pedlar Palmer. After Palmer Rotchford had lost twice more, another ‘DQ’ and a points loss, both to a former foe of McGovern’s in Harry Forbes. However, he had also taken the ‘0’ of one William J. Rothwell, better known as Young Corbett II, a man who would become a legend in his own right a few years later.

What is mainly notable about Rotchford’s win over Corbett, is that he beat him over 20 rounds in the future champion’s Colorado back yard. Also notable is that he went the distance in the first place as Corbett was heavy handed. The bout was pitched to Corbett’s fans as being for the world bantamweight title, though of course this was far from the truth. But Corbett was already a local sensation, and in front of a packed arena Rotchford - who weighed under the modern bantam limit - easily outscored and countered Corbett’s wild swings. Corbett also had a decided advantage in weight, as he came in well over the stipulated 120lbs. Rotchford won the decision for "aggressiveness and superior science".

Billy Rotchford

Never stopped, and having fought some of the best men the lower weights could offer, Rotchford should have been a stiff test for McGovern, especially in Chicago, where Rotchford lived. Instead, Rotchford was left "groping helplessly on the mat" after being knocked down five times according to one local report, and McGovern’s local paper ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ said Rotchford was "helpless and groggy" in a one-sided fight. Another skilled opponent that could not even survive a round with McGovern.

Rotchford would only be stopped one more time in his career, coincidentally enough in the first round as well. The man to turn the trick would be one Harry Forbes.

Despite fighting eight times less than three months after his championship winning fight against Palmer (all knockouts, naturally) McGovern’s stiffest test would be his rematch with Forbes. It would also be a homecoming for McGovern, who had taken his knockout power on the road. He was now a big attraction wherever he went.

Forbes was confident of winning, and reports indicated he he would be a good test for McGovern. His speed and footwork had given McGovern some issues first time round, and he boasted draws with Tim Callahan and feared knockout artist Oscar Gardner, and wins over Eddie Sprague and the aforementioned Billy Rotchford. Against Gardner, a long rumoured suitor for a dust-up with McGovern, Forbes had survived a knockdown and scored two of his own to earn a draw. Gardner forced the fight, so Forbes must have held his own to be given a fair share of it.

"McGovern has already had a taste of Forbes’ quality, and realizes that he will have no such easy task as he had in Cincinnati on Monday, when he knocked out two men in three rounds”, said the ‘World’ pre-fight report.

The same report gave Forbes his due for being "an exceptionally clever fighter", and called him a "remarkable two-handed fighter", likely referring to Forbes’ quick left jab, as well as the sharp right hand which felled Gardner.

‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ acknowledged that both looked strong and in great shape at the weight, but that "Forbes looked like a weakling beside the miniature Hercules". McGovern’s neighborhood paper sure loved him.

In their first fight, Forbes’ quickness and ring smarts had stifled McGovern somewhat, but the Brooklyn boy had found the knockout punch in the end. For this fight, made at 118lbs (the modern bantam limit) McGovern was world champion, but Forbes started in much the same form as in their first duel.

The ‘New York World’ telling of the fight said Forbes "had the best of it" in the early going, winning the battle of "fiddling, feinting and leading", avoiding McGovern’s wild blows and timing his counters well.

McGovern just smiled, and even took time to acknowledge some friends in the audience. But when he tried to fire back, Forbes was smart enough to evade him. The Chicago challenger then landed a stiff left to McGovern’s mouth. "The little wonder looked puzzled" according to the same report.

The ‘Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ report credits McGovern with a knockdown in the first, although other reports do not mention this. On the contrary, the ‘World’ report noted that the only meaningful blows in the first were landed by Forbes.

Perhaps encouraged by his earlier success, Forbes was eager to mix it up more in the second round. He rushed McGovern and swung both fists at him. "Many of his blows landed, but in the mean time Terry was swinging also", said the ‘World’ report. Forbes had willingly jumped into a wood chipper. The ‘Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ report saw a right hand upstairs and a left to the gut, the ‘World’ merely a "left swing", but whatever the punch Forbes went down "dazed" and a nine-count was the result.

Forbes did not get on his bicycle or wrestle with McGovern to try and clear his head. Instead, "he seemed to lose his head and rushed wildly and pinned Terry to the ropes, where both indulged for half a minute in the most terrific infighting seen in a long time". The ‘New York World’ said Forbes was desperate. The crowd jumped up, cheering on the action. It was a war. In the mayhem it was not clear just how much damage Forbes was doing, "but it looked like McGovern was going to be whipped" as Forbes was "fighting him like a tiger".

Many top fighters had folded at their first brush with McGovern’s gloves. But Harry Forbes, buoyed by surviving the hard hitting Oscar Gardner perhaps, was not going to go down without a fight.

It would be his undoing. As Forbes windmilled away, McGovern timed him with a short right hand jolt to the jaw and Forbes dropped like a sack of potatoes. The referee started to count, but the blow was clearly a devastating one as Forbes’ seconds immediately rescued him. "He had no sooner struck the floor than his seconds threw up the sponge, but there was no need for this as there was no possibility of Forbes being able to regain his feet," said the ‘Daily Eagle’ report.

First time round, Forbes had battled his way through 14 rounds before being blasted. This time, with more experience on his side, he hadn’t got out of two sessions without being lumped.

Terry McGovern vs Oscar Gardner, 1900. Gardner was a good fighter, and he could punch.

Credit: Boxing History, Facebook

"Terrible" Terry McGovern defended the world featherweight championship with a 3rd round KO of Oscar Gardner at the Broadway Athletic Club in New York, New York on March 9th, 1900.

By this point McGovern was known by audiences as a stout battler and a good puncher, while Garnder, "The Omaha Kid" who was actually from Minneapolis, also had a reputation as a hard puncher. Gardner was in his 10th year of fighting as a professional, however, and long in the tooth compared to the the young man, who turned 20 on the day of the bout.

In round 1, Gardner caught McGovern with a right hand that dropped him. McGovern immediately latched onto Gardner's leg, and the challenger dragged McGovern across the ring to try and shake him loose, which took several seconds. McGovern got up and glued himself to Gardner to fight in the clinch.

"The second round was all Terry's," one report said. "Every second of it. Gardner knew he was in it, but that was all. He landed one feeble blow somewhere between the gongs, but no more, and that didn't count. The rest of the time he was picking himself up from the floor to which McGovern had sent him with jolts and swings."

McGovern sent Gardner down four times in round 2, returning the favor and then some. Then in the 3rd, McGovern tore at Gardner and landed a left hook that rendered him unconscious.

"[The punch] was a rip-razzler, and it is a wonder that it did not knock Gardner all the way from here to Omaha where he originally came from," said a report.

In 1904, PHILADELPHIA, Oct. 10.-Terry McGovern was delivering such severe punishment to Eddie Hanlon of California in the six-round bout at Industrial Hall that the police stopped the contest in the fourth round. Hanlon was hanging on the ropes in a helpless condition when the police interfered.

Comments

This is Johnny Coulon in his prime, during his fighting days. He was involved in boxing for his entire life.

Coulon, also called "The Cherry Picker of Logan Square," began boxing at only 8-years-old and trained under his father, Pop Coulon. Later he trained with Elbows McFadden, George Siddons and James Corbett. His early boxing experience helped him become one of the youngest title claimants of all time at 18, when he defeated Kid Murphy for a portion of the bantamweight title.

A two-fisted slugger, Johnny Coulon turned pro in 1905 just three weeks before his 16th birthday. He was born in Toronto, Canada but for most of his life he resided in Chicago.

Coulon won his first 26 bouts before losing a 10-round decision to Kid Murphy. In a rematch with Murphy in 1908, Coulon reversed the decision and earned recognition as the American bantamweight champion.

On March 6, 1910, Coulon captured the vacant world bantamweight crown when he defeated England's Jim Kendrick in 19 rounds. He defended the title against Earl Denning, Frankie Conley, Frankie Burns and Kid Williams. He finally lost the crown in 1914 when Williams stopped him in the third round.

There was eventually no question as to the strength of his claim and he held the championship until 1914, when it was said he was well past his best and had been weakened by illness.

But Coulon was a skilled and scientific fighter, and he later opened Coulon's Gymnasium with his wife in Chicago, with fighters like "Sugar" Ray Robinson, Joe Louis and Carmen Basilio training there on occasion. Coulon even became one of the first ever former world champions to officially handle a current champion when he trained the great Eddie Perkins.

Throughout his life, Coulon stayed in shape. "I have never drank of smoked and I try to instill this in the boys, not by preaching but by just talking, and it seems to go over."

Coulon served in the U.S. Army during World War I, often instructing soldiers on how to fight. He boxed twice after his service stint and retired from the ring in 1920.

On his 72nd birthday, Coulon showed off for reporters by walking around the gym on his hands, it was similar to his "unliftable man" trick, he liked to show off his various tricks and skills .

When Coulon died at 84-years-old in 1973, he took an encyclopedia of boxing knowledge with him.

''The toughest opponent is me. A Iot of times, you don't want to train. You don't want to box. Sometimes, life hits you to the point where you don't even want to live. You have to fight with that person. You have to make yourself wake up in the morning. You have to make yourself watch your weight. That's how I fight with that person.'' - OIeksandr Usyk

Prime George Foreman at his most frightening, as he clubs Joe King Roman senseless.

Foreman made his first defense of the heavyweight championship with a brutal and cruel 1st round KO of Joe King Roman at Nippon Budokan in Tokyo, Japan in 1973.

Roman, a Puerto Rican heavyweight who fought out of Florida, was no match for Foreman. When Roman tried to move early, Foreman cut off the ring and trapped him near the ropes. A left hook caught Roman on the temple and sent him down into the ropes quite awkwardly, and Foreman then caught Roman with a right hand as he was down (pictured).

Action stopped as Roman's corner protested, but their fighter claimed to be okay, the referee ruled no foul was committed and Foreman appeared somewhat apologetic. When the fight resumed, a whirling right hand caught Roman and knocked him flat. He beat the count only to be caught with a few more punches, punctuated by an uppercut that crumbled him to the canvas, all but unconscious, where he was counted out.

Another shot of that George Foreman clubbing, man that is brutal.

William Rothwell, known as "Young Corbett II", early 1900s featherweight champion and Hall of Famer. It's a fascinating story, Young Corbett II pulled off a massive upset on this day in 1901 when he KO'd "Terrible" Terry McGovern in Round 2 of their fight in Hartford, Connecticut, to win the world featherweight crown. It's fascinating because Terry McGovern was one of the most feared fighters in boxing history, they didn't call him "Terrible" for nothing, he left a trail of destruction across two divisions on his way to the top of the bantamweight and featherweight mountains. Terry McGovern's reputation is well known to boxing fans, he was the Mike Tyson of his era. His ring record is littered with bodies, he was one of the hardest punchers in the history of the featherweight division and one of the most violent men to ever step foot in the ring. To say he was feared during his time would be an understatement. By 1901 McGovern had seized the bantamweight and featherweight titles by brute force, and was thought of as being invincible or damn near it. Enter Young Corbett II, he was from Denver, Colorado, and though Young Corbett had registered victories over former champion George Dixon and contender Oscar Gardner, he wasn't a well-known pugilist and wasn't given much of a chance to defeat the supposedly invincible featherweight kingpin, Terry McGovern. Corbett, who was trying to prove that he was by no means intimidated of McGovern's reputation, banged on the McGovern's dressing room door before their fight and jeered him by reciting some nasty remarks and insulting him. Now that takes some serious guts, and is one of the boldest things I've ever heard of, can you imagine someone busting through the door of prime Mike Tyson's locker room and taunting him before a fight? But Corbett did exactly that, then proceeded to back it up in the ring by knocking Terry McGovern out. The crowd was was absolutely stunned. It's insane to pull something like that off one time, but in the rematch in 1903, Corbett stopped him in 11, proving the first time wasn't a fluke.

Young Corbett II in his prime

Hall of Fame Athletes / 1978 Inductees / Young Corbett

Young Corbett, Denver’s first and only world boxing champion, was inducted into the Colorado Sports Hall of Fame posthumously in 1978 after gaining national fame and becoming a hometown hero in Denver.

The recognition by his native state seems long overdue and comes after he took his place among the ring immortals by being elected to the Boxing Hall of Fame in 1965.

Corbett received national attention when he knocked out “Terrible” Terry McGovern in the second round of a featherweight title fight in Hartford, Connecticut, November 28, 1901.

William H. Rothwell was born in Denver, October 4, 1880. It was on Swansea Street that he first learning to protect himself by using his fists. When he started fighting professionally at the tender age of seventeen, he took his ring name after his manager, Jimmy Corbett. Boxing was popular in the rip-roaring mining towns of Colorado and Corbett had several fights in such towns as Leadville, Cripple Creek and Aspen.

Standing only five-feet two-inches tall, he gained acclaim as a deadly puncher. In a memorable fight in Denver, he stopped Oscar Garner in the second round and then beat Kid Broad and ex-champion George Dixon.

After his forty-second fight, Manager Corbett figured the time had come to take his protégé east, and a title bout with Terry McGovern was negotiated. It was considered a mismatch by most eastern critics, as McGovern was viewed, pound for pound, one of the deadliest punchers in the boxing game. In the previous two years he had scored seventeen knockouts, including a string of twelve straight.

The betting gentry wagered the feisty twenty-one year old from the Rockies would take the count within five rounds. Although the featherweight limit was 122 pounds at the time, by mutual agreement the fighters agreed to scale in at 126 pounds. It was a slam-bang battle from the opening bell. Corbett ripped over a right to the jaw late in the first round and the champ went down but jumped up without a count.

Early in the second round another right to the jaw floored McGovern, but again he leaped to his feat without taking a count. The champion fought back, but Corbett refused to give ground, landing a vicious uppercut to the champ’s jaw and McGovern landed on his back and was counted out. A new champion was born.

Corbett’s victory touched off a wild celebration back home in Denver, and Corbett’s mother, two sisters and younger brother were the focus of national attention.

Unfortunately, Corbett’s fame was short lived. Unable to make his weight, he had to relinquish his featherweight title. Abe Attell, who fought many of his early fights in Denver, was recognized as the featherweight champion.

Corbett campaigned as a lightweight with moderate success, then returned to Denver for his last fight against Kid Broad in 1902. Corbett began instructing youngsters and retired in 1910 with a record of thirty-four knockouts in 104 fights.

Corbett died in April, 1927, only a few months after he had appeared in an exhibition at the Elks Club against Mike Mongone, an opponent in his early days in the mining camps.

This is a photo of "Terrible" Terry McGovern (left) and Young Corbett II before their famous 1901 encounter.

This is another photo of Terry McGovern (left) and Young Corbett II before their 1901 fight, my god, look at Young Corbett II, he's built like a damn tree trunk.

An original newspaper article from 1901 after the first McGovern-Corbett II fight.

On March 31, 1903, at Mechanics Pavilion in San Francisco the rematch between McGovern and Corbett II took place, it was a violent fight, and Corbett knocked out McGovern in the 11th round, as was the case in their first fight, the finishing blow was an uppercut. There was controversy, the controversy stemmed from claims that McGovern might have been the victim of a faulty referee's count, though the fight result of Corbett winning by knockout in the 11th round is generally accepted.

"William Rothwell, better known as Young Corbett of Denver, showed decisively tonight that his victory over Terry McGovern of Brooklyn at Hartford a year ago was no fluke by defeating McGovern in the 11th round after a fight in which there was not a second of idleness for either man. In nearly every round Corbett, fighting like a machine, never overlooking an opportunity to send home his blows, had a shade the better of the argument, and when finally in the 11th round he got the Brooklyn boy fairly going he never let up on him, until Terry sank to the floor a badly defeated man. There was some question as to whether or not McGovern was down at the count of 10. McGovern tried to get up and was on his feet an instant after the timekeeper counted him out. As it was, it was nearly a minute after McGovern had been carried to his corner before he was able to sit up and understand what had happened." - The Boston Post

McGovern was also down once each in the first two rounds. The ring was momentarily invaded by McGovern supporters who believed McGovern had beaten the count, but the police immediately piled them through the ropes and restored order. Post fight comments:

"The final blow was a right uppercut to the jaw that put McGovern to the floor for the full count. Even had he been able to regain his feet before the count of 10 I would have had him out, as he was absolutely unable to defend himself." -Young Corbett II

"It was the greatest robbery in the history of the prize ring. I had Corbett beaten from start to finish. I landed on him when and where I pleased and surely would have had him out within a few rounds. I was not knocked out, but admit that the right uppercut to the chin dazed me and I took the count in order to save myself." -Terry McGovern

This is an actual ticket from the McGovern-Corbett rematch in 1903, awesome item.

This is my favorite photo of Young Corbett II, would love to own the original type 1 copy of it. He was a bada$$.

Like I said, "Terrible" Terry McGovern was no joke. He was an Irishman from Brooklyn, New York, they called him "The Brooklyn Terror", he struck fear in hearts of his opponents and up until he met his kryptonite in Young Corbett II, McGovern was a wrecking machine.

“Terrible” Terry McGovern

By: Monte D. Cox

The name Terry McGovern might not mean much to boxing fans today, but in his youthful prime he was one of the most awesome hitters in boxing history. His punching power put fear into the hearts of fighters from bantamweight to lightweight. McGovern was like a little Mike Tyson destroying opponent after opponent during his short, but devastating reign of terror.

Stylistically there are many similarities between Terry McGovern and Mike Tyson. Both were stocky built, swarming style hitters who came in low and wrecked their opponents with sharp and powerful counter punches. Like Tyson, McGovern had a seek and destroy mentality from the opening round.

Prior to the coming of Terry McGovern fans did not like to watch fights that ended almost as soon as they began. The boxing crowd and the gamblers who ran the sport liked to see drawn out boxing exhibitions that featured sparring for openings, masterful defense, and a relatively slow pace until an opponent made a mistake. The longer a fight went the more money that could be placed on bets by the gamblers and the fighter’s financial backers. It was common to see the elite fighters carry an opponent to cash in on the stakes. McGovern cared nothing for that. He came out of his corner like a hungry lion who was ready to feed and attempted to devour his opponents in the shortest amount of time. When McGovern exploded on the scene he electrified the crowds with his fast attacks and devastating, shocking early round knockouts. No one had seen anything quite like him before. McGovern scored 23 of his 44 career knockouts in 3 rounds or less.

The National Police Gazette characterized him thusly; “Terry’s style of fighting was a never ending source of delight to the thousands who saw him for the first time in a ring engagement. He was as fast as a streak of lightning, and the large crowd was amazed at his great footwork…Terry has wonderful control of himself in a mix-up and never gets rattled. He would go in like a steam engine and slip away like a snake. This was one of the most notable features of his work in the contest. He was always fighting but never let his opponent hit him to any extent.”

McGovern was a hand held high, ducking, slipping, and short armed puncher much like heavyweight Tyson. “Iron” Mike was known for his defense, slipping and countering to get inside. McGovern fought much in the same manner, the Gazette reported, “McGovern’s defense was perfect and his delivery fast and furious.”

After his fight with Billy Rotchford the Gazette described McGovern with the following, “He hooks fast and punches straight and has a remarkably swift punch, moving over the shortest possible space, and both hands are capable of working evenly, smooth and fast as two pistons. The position in which he had his mitts drew up his shoulder and protected his chin and neck. The elbows were ready to drop to stave off rib blows, and the hand, either right or left, prepared to slip inside any swing or wide hook an opponent might deal up.”

When Tyson was “on” he was a strong body puncher as in the Jesse Ferguson fight, but Tyson was never the pound for pound puncher to the body that McGovern was. Historian Barry Deskins wrote, “Short blows to the body followed by a viscous straight right is McGovern’s strongest asset, particularly his work to the body.” Old time fight announcer Joe Humphrey’s said, Sept 1936 Ring Magazine, “McGovern was a lightning fast feinter and a terrible hitter. He was a great body puncher, an art that seems to be lost to the present generation.”